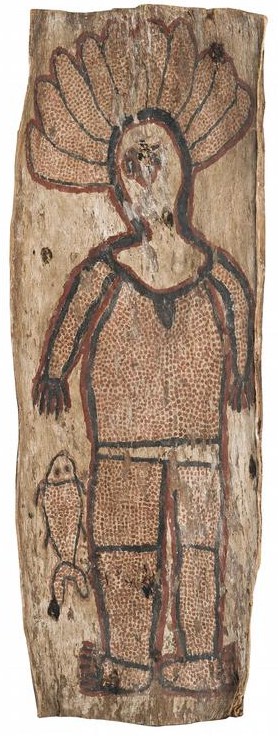

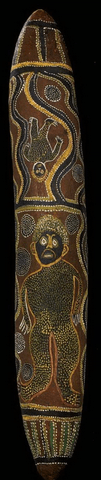

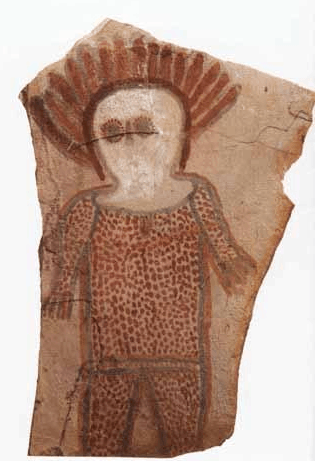

Wattie Kaduwara Wandjina paintings

Long Wattie Kaduwara is a famous Wandjina painter form the Kimberley in Western Australia. He was one of the pioneer commercial wandjina painters. The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their a bark painting/slate is by Wattie Kaduwara by comparing examples of his work.

If you have a Wattie Kaduwara bark painting or slate to sell please contact me. If you just want to know what your Wattie Kaduwara painting is worth to me please feel free to send me a Jpeg because I would love to see it.

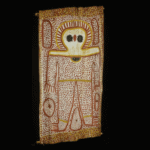

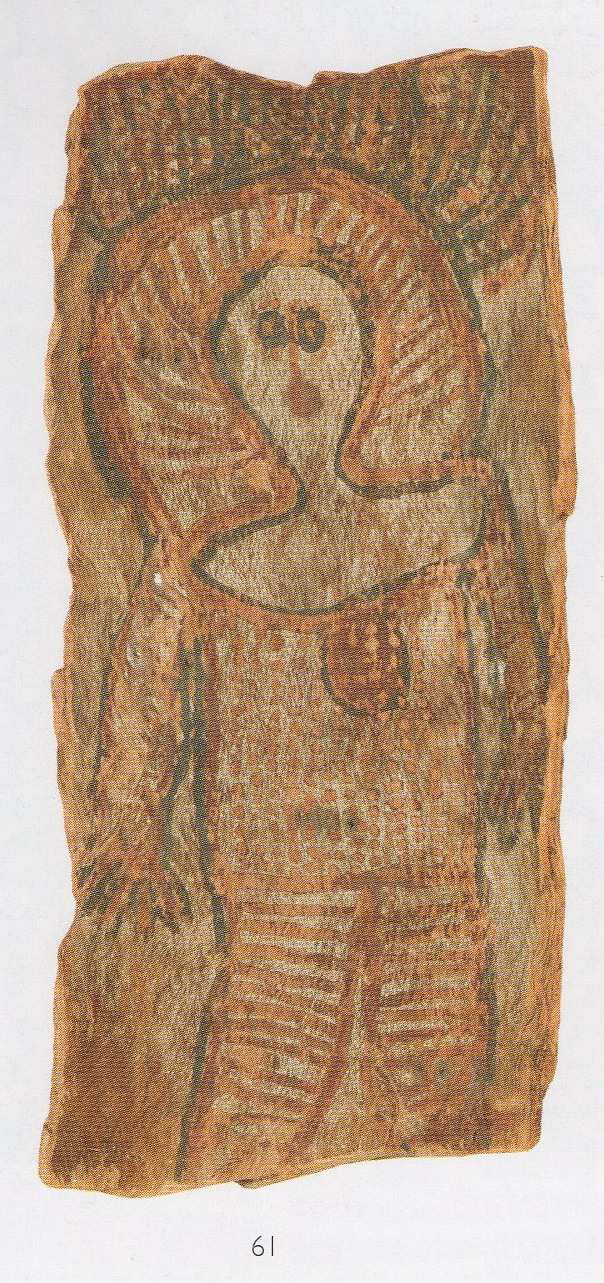

Wattie’s Wandjina figures are drawn with a full body. The figures are drawn in an inland wandjina style with very large head-dresses which look more fan shaped than hallo shaped. Wandjina takes many forms according to the exact location and tribal group that are its custodians and Watties images represent those from his area. The bodies are usually covered with red. His wandjina faces vary but often don’t have eye lashes and sometimes have eye brows. Watties Wandjinas have small eyes, nose, and delicate hands and feet.

Wattie Kaduwara was born in the Hunter River basin in the Kimberley around 1910. In 1921 during his youth, two shipwrecked sailors stole a canoe from a clansman and, in an attempt to cross the Hunter River, became swamped. On their return to shore, the owner of the canoe speared and killed them. As a consequence the police detained four women and two men, of whom Wattie was one. After a period in Wyndam jail and a trial in Perth, Wattie Karduwara was eventually released as a minor. He spent nearly 20 years in Perth before returning to his home at Mowanjum.

Biography

In Mowanjum, Wattie lived with his uncle Mickey Bungkuni a senior Wunambal elder who painted wandjina and taught Wattie to paint. There are a few early examples of Watties works collected by anthropologists before 1970. The majority of his paintings were done in the early 70’s. Wattie Karduwara and Charlie Numbelmoore were among the first artists to emerge as individual artistic identities prior to the 1970’s. Although most of Watties works are on bark he also painted coolamon and on

Wattie was born in the Hunter River (Mariawala) basin, an area known as Elalemerri to the

His clan is known as Landar after the small yellow-flowered, holly-leaved, pea-flower, Bossiaea

Wattie late in his career did a series of watercolors and painted

More Kimberley

Artworks and Articles

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Wattie Kaduwara Wandjina Images

The following is not a complete list of works but gives a very good idea of this artists style and variety.