Understanding the meaning of Aboriginal Art

To truly understand the meaning of Aboriginal art, one must look beyond surface aesthetics and delve into the cultural and spiritual narratives embedded within the artwork. One of the most accessible ways to grasp this depth is by examining Aboriginal artworks with documented meanings, especially those directly connected to the artists’ ancestral Dreaming stories, Country, and kinship systems.

The most significant and well-recorded collections in the history of Aboriginal art are the early Papunya paintings created between 1971 and 1974. During this foundational period of the Western Desert Art Movement, art teacher Geoffrey Bardon worked closely with more than 25 Aboriginal artists, helping to document the symbolism and stories behind several hundred artworks.

The book Papunya A place made after the story is a 500 page illustrated book and remarkably good value. It certainly deepens my understanding and is highly recommended.

These early Papunya works are vital for anyone seeking to understand what Aboriginal art means—not just visually, but culturally. They demonstrate how Aboriginal art serves as a story map, a teaching tool, and a spiritual record. The symbols used—such as concentric circles, U-shapes, and animal tracks—are not merely decorative. They encode ancestral knowledge passed down through generations and tied intimately to place, ceremony, and identity.

Birds Eye view

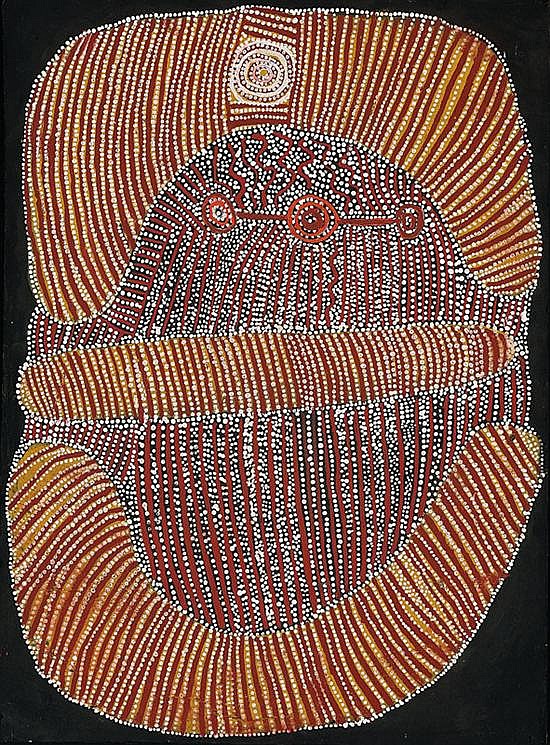

Aboriginal art is traditionally painted from a bird’s eye view, reflecting the ancestral perspective of looking down upon Country rather than from the human eye level. This aerial viewpoint is central to understanding the meaning of Aboriginal art, as it conveys a spiritual and topographical mapping of land, custom-story, and ceremony.

The scale in Aboriginal paintings varies depending on the narrative: a ritual ceremony might be depicted as if viewed from just 50 feet above, showing intricate details of a ceremony, while a Dreaming journey may stretch across vast distances, with symbols representing places hundreds of miles apart.

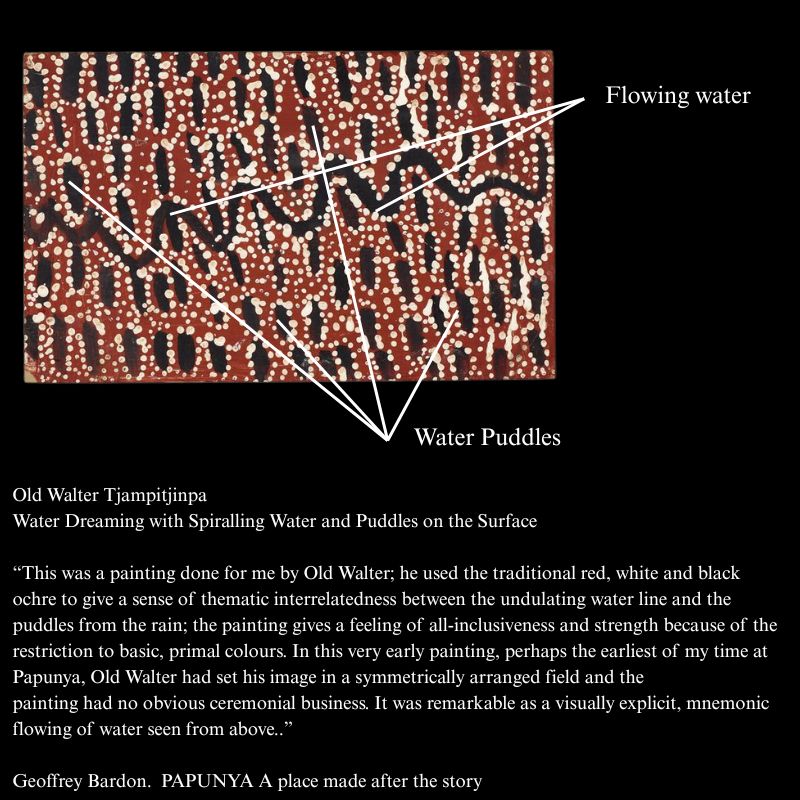

A simple example is Old Walter Tjampitjinpa’s Water Dreaming, which evokes the sensation of flying low over the desert, where large black puddles gather in the red earth and a temporary creek winds through the centre—capturing both the visual and spiritual rainmaker essence of the landscape. Due to the top-down orientation, traditional Aboriginal artworks from this region do not have a right way up.

Spiritual cartography

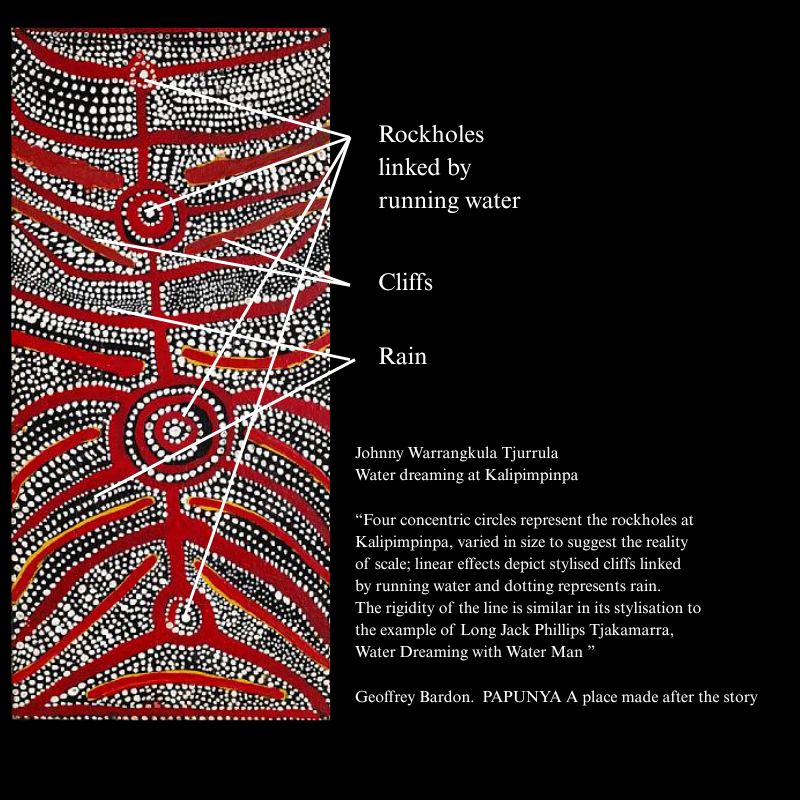

Spiritual Cartography is a fundamental concept in understanding the meaning of Aboriginal art, where the scale and placement of elements are not dictated by physical proportions but by their spiritual and cultural significance within the story being told. Unlike an aerial photograph, an Aboriginal painting is not a literal representation of the landscape—it is a sacred map, where Country is depicted through the lens of ancestral knowledge and Dreaming narratives. In this visual language, a rockhole or ceremonial site may appear disproportionately large, not because of its physical size, but because of its importance within the songline or story. For example, in this artwork by Johnny Warrangkula, the largest rockhole depicted may not be the biggest geographically, but it holds the greatest spiritual weight and therefore dominates the composition.

Inter-relationship

Inter-relationships especially spiritual inter-relationships are at the heart of traditional Dreaming stories and are key to understanding the meaning of Aboriginal art, which often illustrates the deep connections and oneness between people, land, custom animals, plants, and ancestral forces. These stories do not just describe the physical world—they reveal the spiritual relationships that sustain it.

In Johnny Warrangkula’s Rain Dreaming (below), for instance, the Yala bush potatoes and wild raisins are depicted as growing from the central waterhole known as Tjikari. This is not a literal representation of where these plants are found, but a symbolic expression of Tjikari’s ancestral power—it is the source of rain that gives these foods life and existence.

Simarly the presence of churinga (sacred ceremonial objects) and the ancestral waterman in the painting highlights the magical and spiritual interactions with Tjikari the sacred waterhole that are required to bring about rain, demonstrating the interconnected roles of natural and spiritual beings.

Spiritual not spacial relationships

Spiritual, not Spatial Relationships are a defining feature of traditional Aboriginal art. Unlike Western cartographic representations, Aboriginal artworks depict spiritual connections rather than physical arrangements.

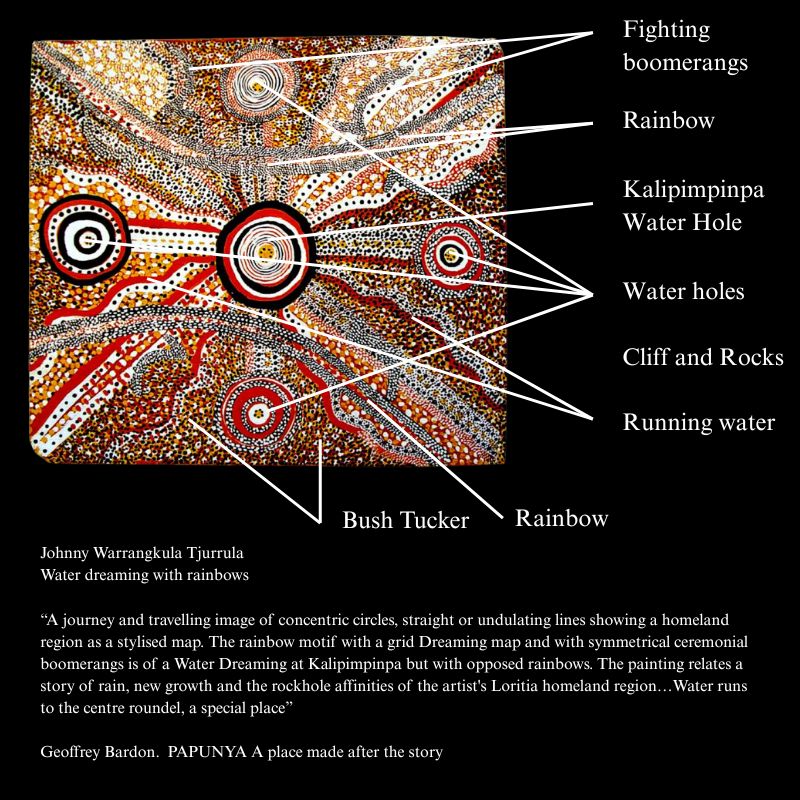

In this Water Dreaming painting, the central waterhole Kalipimpinpa is shown evenly surrounded by four subsidiary waterholes. While an aerial photograph of the actual landscape would not reveal this symmetrical pattern, the artwork is not concerned with geographic accuracy. Instead, it illustrates the spiritual relationships—the fact that all four waterholes are connected to Kalipimpinpa and are all part of the same spiritual entity is what is being illistrated.

Think of it as spiritual conception. This was a sharing of knowledge not just pretty dots.

This form of sacred mapping prioritises meaning over measurement, conveying how these sites interact within the spiritual and ceremonial network of Country.

The painting becomes a visual expression of interconnected power, where the central site holds significance not just in location, but in its role as the source or conduit of life-giving water. This approach reflects a core principle of Aboriginal art: that what matters is not where things are, but how they relate spiritually and culturally, reinforcing that Aboriginal art is a system of knowledge transmission, grounded in Tjukurpa (Dreaming Law) rather than in Western ideas of space or scale.

Depictions of Ceremony in Aboriginal Art

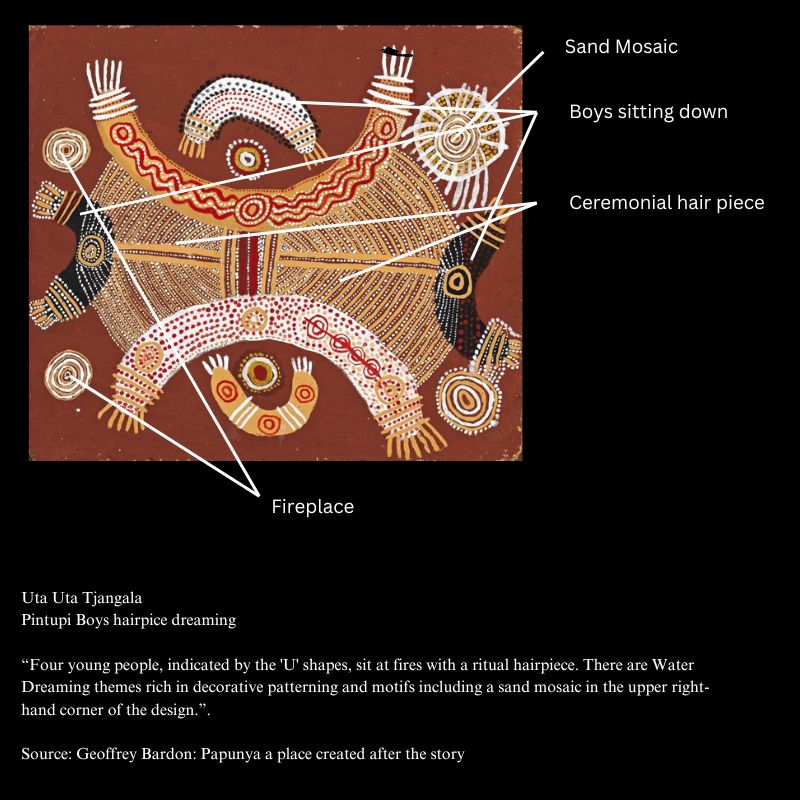

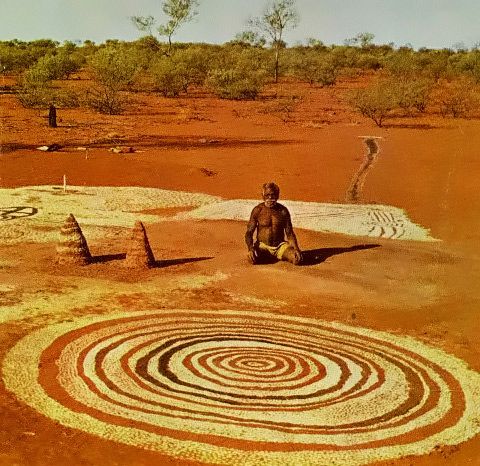

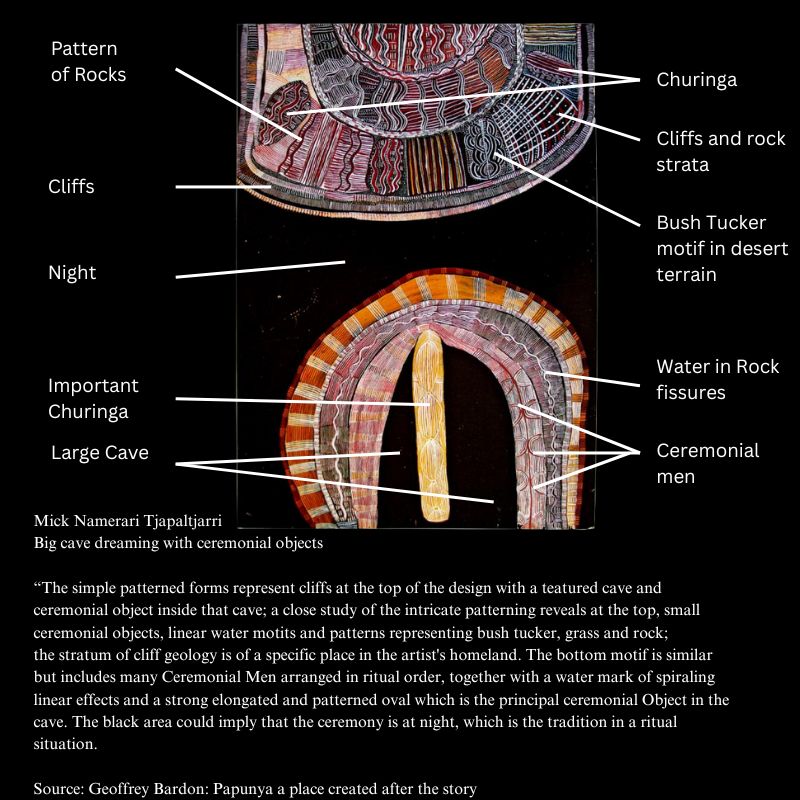

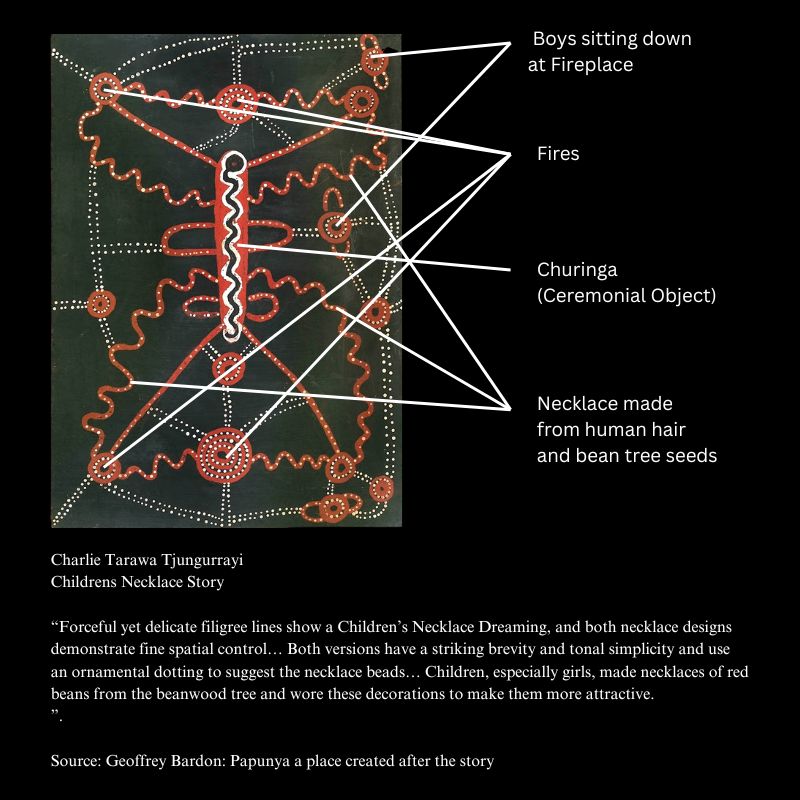

Visual symbols, sacred sites, churinga and ritual performance are deeply intertwined. In many traditional contexts, the culmination of Aboriginal ceremonies took place directly upon large sand mosaics, intricate ground designs rich with spiritual and religious meaning. These mosaics were not just ephemeral artworks but active ceremonial spaces—initiates would dance and chant upon them, becoming part of the living artwork and empowering the ancestral Dreaming stories embedded within the ground.

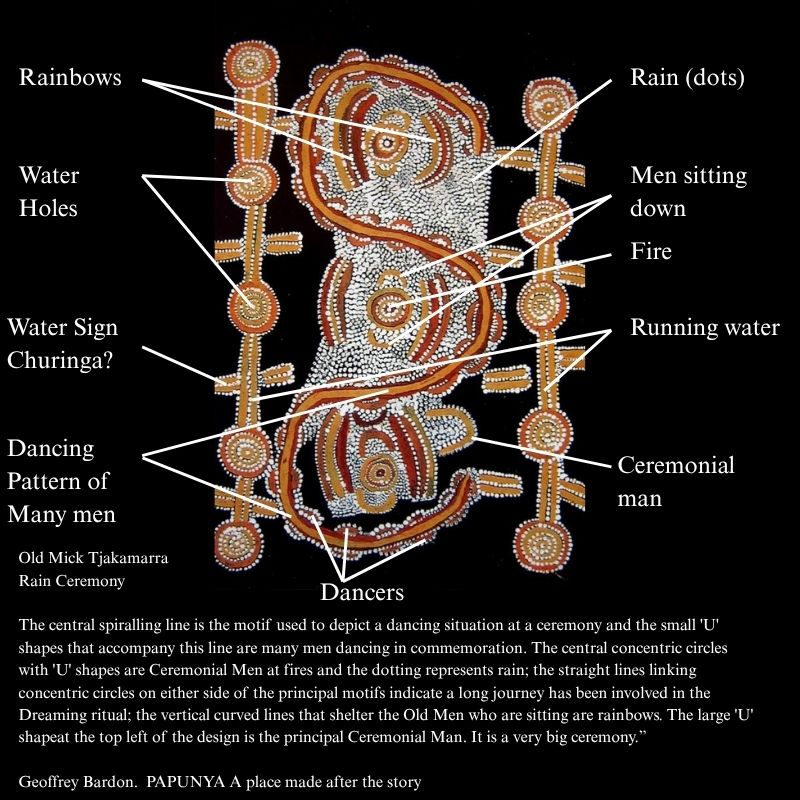

A powerful example is Old Mick Tjakamarra’s Rain Ceremony, a painting that captures the spiritual energy and layered symbolism of such a ritual event. Like many traditional Aboriginal artworks, it operates on multiple levels of meaning. For instance, while the three sets of concentric circles are campfires, within the ceremonial context of the sand mosaic, these fires are also symbolic extensions of Tjikari, the central waterhole and spiritual focus of the rainmaking ceremony. When one recognises that the symbol for Tjikari is three concentric circles and that this is a depiction of rain ceremony, it becomes evident that the sand mosaic as a whole is a spiritual map of Tjikari.

This layered symbolism exemplifies how Aboriginal art conveys sacred knowledge—each element within the composition is a vessel of cultural law, story, and power.

Even among aboriginal people there were multiple levels of knowledge about symbolism and true meaning. Only a guardians knew the whole story. The ceremonial man or guardian to the story is depicted as sitting within the ceremonial sand mosaic.

Aboriginal Symbols: Visual Echoes of the Dreaming

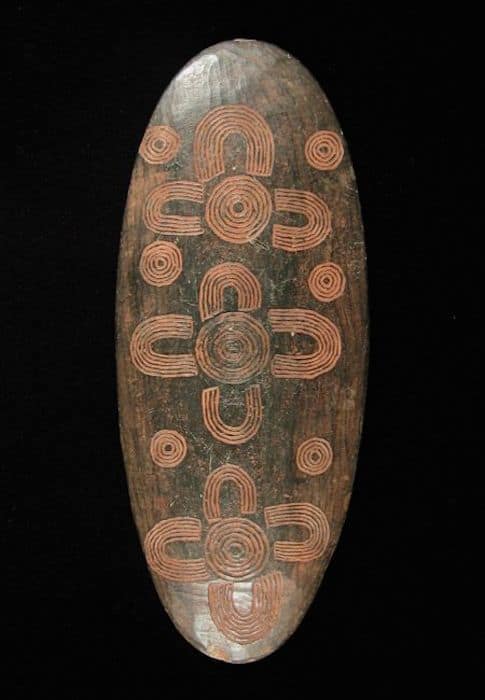

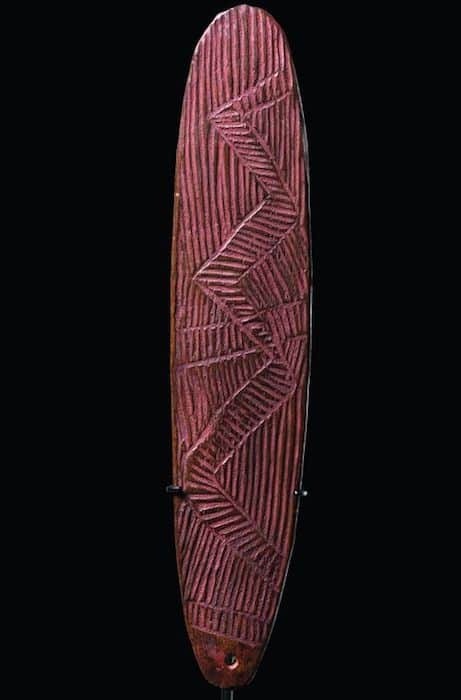

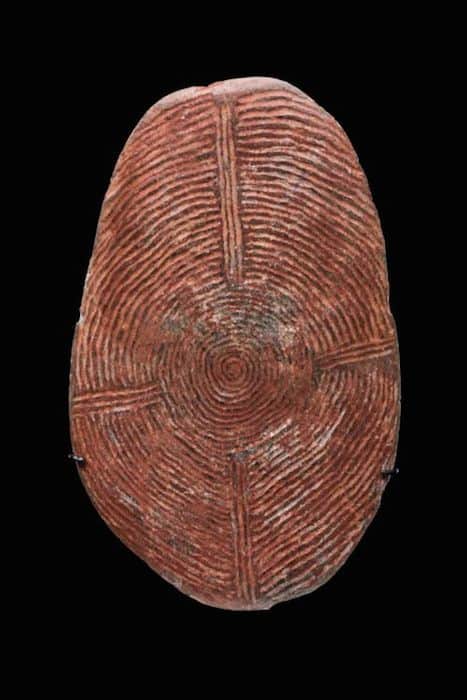

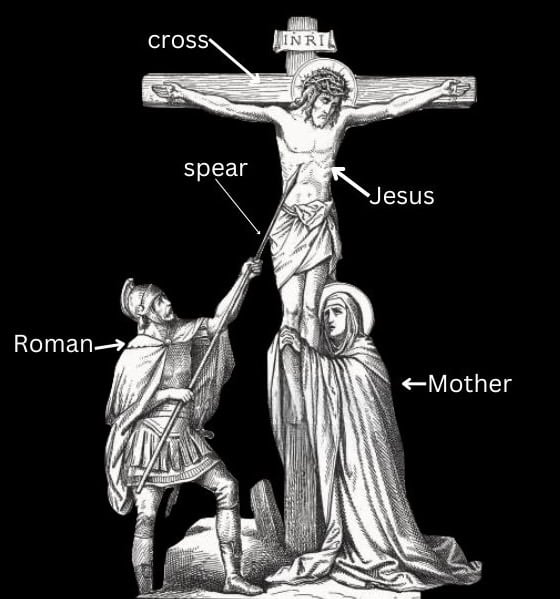

The symbols found on Churingas and in early Aboriginal artworks are far more than decorative elements—they are sacred markers that illustrate parts of a songline, or Alcheringa story, which lies at the core of an artist’s spiritual and cultural identity. These visual symbols represent just a fragment of a much deeper, sacred narrative—like a single frame from a vast and complex film about the life of christ.

To draw a comparison, opposite is an artwork depicting a scene from a well-known Christian story, the Crucifiction. While the image and its description may be accurate, they only touch the surface of the full theological and cultural significance behind the event. True understanding requires immersion in the broader belief system.

The same principle applies when interpreting Aboriginal art: while a symbol might accurately represent a waterhole, a journey, or a sit down place, its full meaning can only be understood within the larger context of the songline it belongs to. Aboriginal symbols do not function like a written language or hieroglyphics, where meaning is fixed and literal. Instead, their significance is shaped by their placement, their relationship to other symbols, and their connection to the sacred narrative being depicted. These symbols are not simply visual codes—they are spiritual waypoints, guiding those with cultural knowledge through the ancestral pathways of the Dreaming.

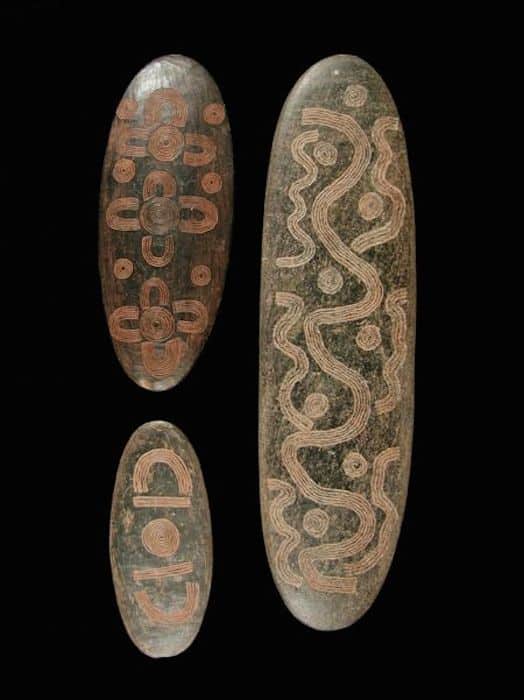

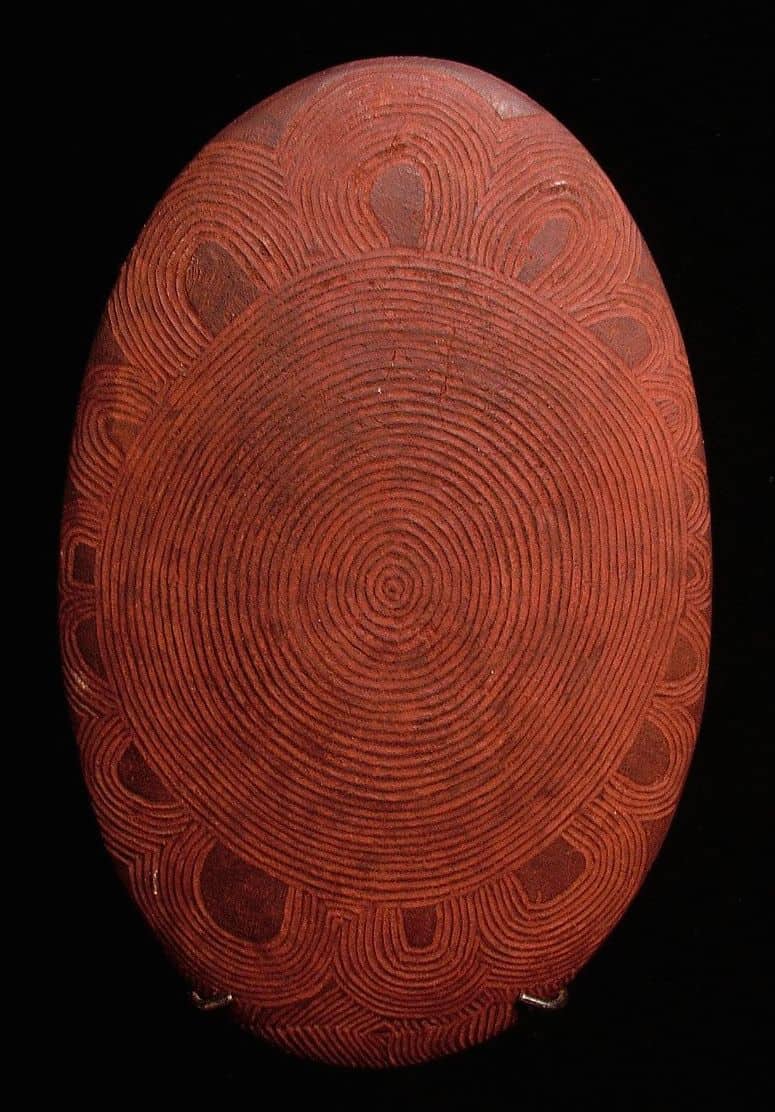

Churinga: Sacred Objects of Ancestral Power

Churingas are sacred spiritual objects central to Aboriginal belief systems, particularly among Western Desert communities, and they form the foundation of many early Aboriginal art designs. Unlike paintings created for public viewing, traditional Churinga designs were not painted but carefully incised into flat, oval-shaped pieces of wood or stone. These are not artworks in the Western sense—they are deeply sacred objects that embody ancestral power and identity. According to customary Aboriginal belief, when a woman becomes pregnant, it is not merely a physical event but a spiritual one: an Alcheringa, or Dreaming spirit, is believed to have entered her body, initiating the pregnancy and becoming the child’s spiritual father. The woman can identify which Alcheringa has caused the conception based on the sacred site she was near at the time. After the child is born, it is believed that the Alcheringa spirit places the child’s Churinga near the mother’s place of conception. This sacred object is then placed in a hidden storehouse known only to initiated men—a repository for the Churingas of all those conceived by that same ancestral spirit, both living and deceased. It remains hidden and protected until the male child reaches the age of initiation. Only then is he shown his Churinga and taught the sacred songs, ceremonies, stories, and spiritual knowledge tied to the Dreaming that brought him into existence. The Churinga is not just a symbol; it is a vessel of ancestral energy and a key to spiritual identity.

The Power of Aboriginal Art: Ceremony, Spirit, and the Sacred Connection to Country

The true power of Aboriginal art lies in its deep spiritual connection to ceremony, Country, and ancestral alcheringa presence. In traditional Western Desert cultures, art was never merely symbolic—it was an active force. Ceremonial practices, such as painted initiates chanting sacred songs to Tjikari while dancing on sand mosaics depicting sacred designs, were believed to awaken the spiritual energy of that specific Dreaming sites. These rituals, conducted under the guidance of a songline custodian and surrounded by carefully placed Churinga, could invoke an ancestral Alcheringa spirit—a forces so potent they were said to influence natural events, such as bringing rain..

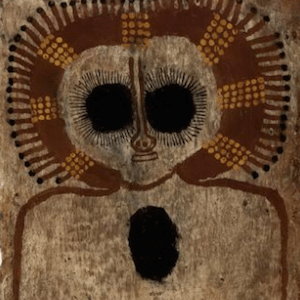

Just as prayer holds meaning in Christianity, Aboriginal art and ceremony served as a kind of spiritual technology—a visual and ritual language for shaping reality. Art in this context functioned as a conduit between the physical and the ancestral realms, embodying a worldview where people, spirit, land, art and future are intertwined. Traditional Aboriginal Art throughout Australia was made as a spiritual technology be it the Wandjina paintings of Alec Mingelmanganu or the bark paintings of Namatbara or depictions of Namarrkon on rock shelters aboriginal art was far more than mere aesthetic.

Conclusion: Meaning of Early Aboriginal Paintings

Early aboriginal artists painted their traditional designs while chanting. They were singing the travels of the Alcheringa spirit and sacred place that bought them into existence. Many of the most important pieces were empowered through song. These stories sung of the travels of the Alcheringa are depicted by the symbols they paint.

They were painting elements of their songlines or dreamings.

Early aboriginal artist on a spiritual level are the children of an Alcheringa spirit that resides at a particular sacred site. So when they paint a particular Alcheringa sacred design it is a place, a spirit a story a culture and a part of themselves.

So, for example, Old Walter Tjampitjinpa was the senior custodian for the a Water dreaming. Being senior custodian meant he looked after the storehouse for all the churinga of all the people ever conceived near that sacred site. It also meant he had more knowledge of that story, that dreaming, that songline than the average initiate.

When he paints the water dreaming he is not just painting a place, he is painting elements of his alcheringa he is painting a part of himself.

If you have an interest in the symbology and meaning of artworks by a specific artist I have included examples of these at the end of my articles about each aboriginal artist.

The Meaning of 10 Aboriginal Paintings

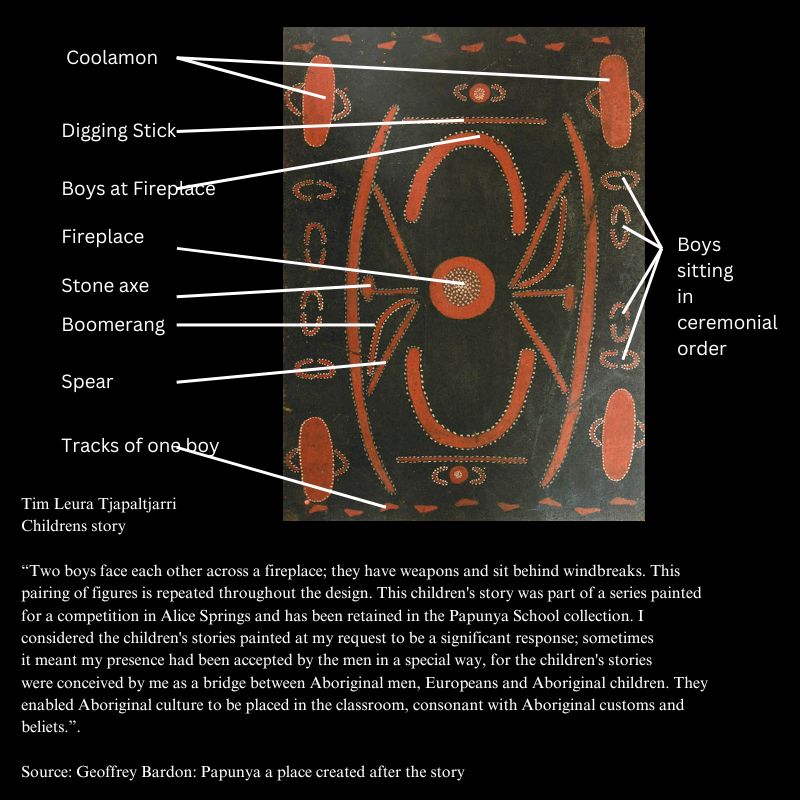

Opposite: Painting by Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri

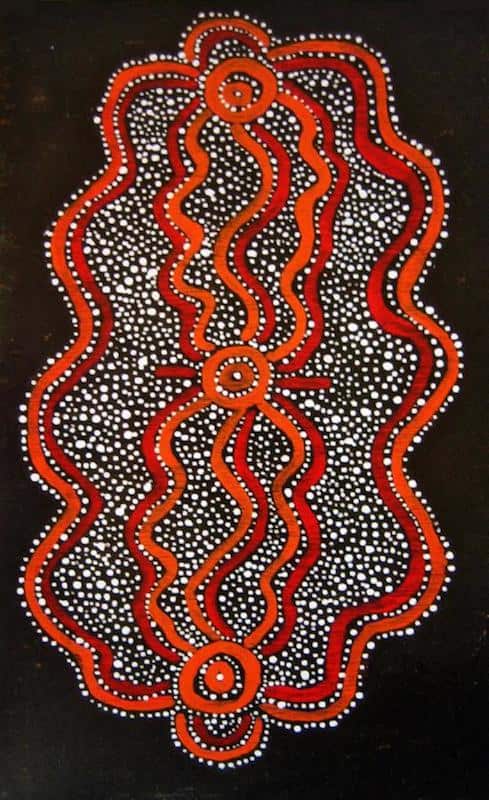

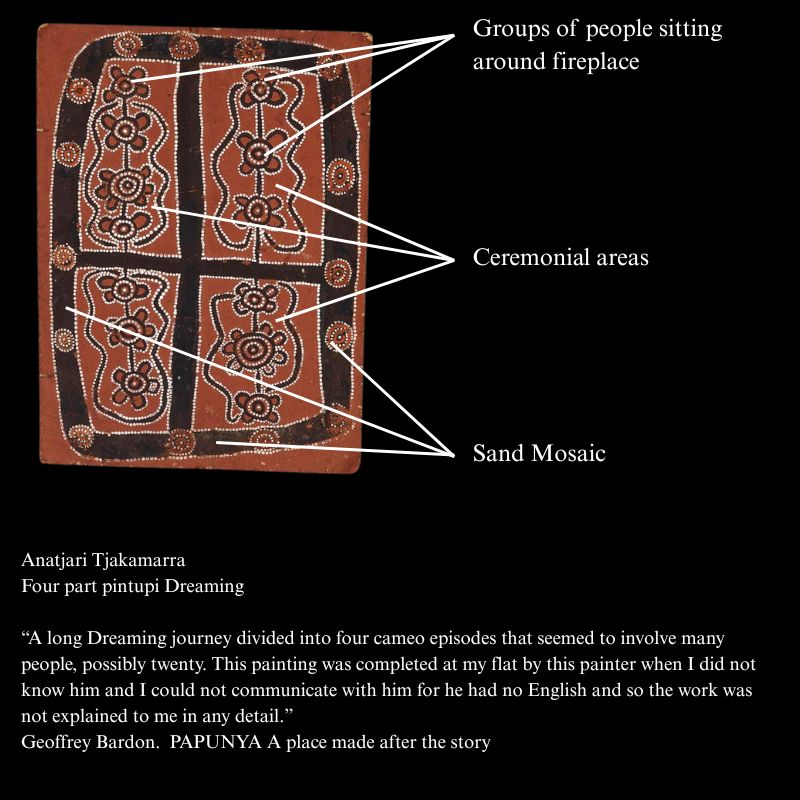

Opposite: Painting by Anatjari Tjakamarra

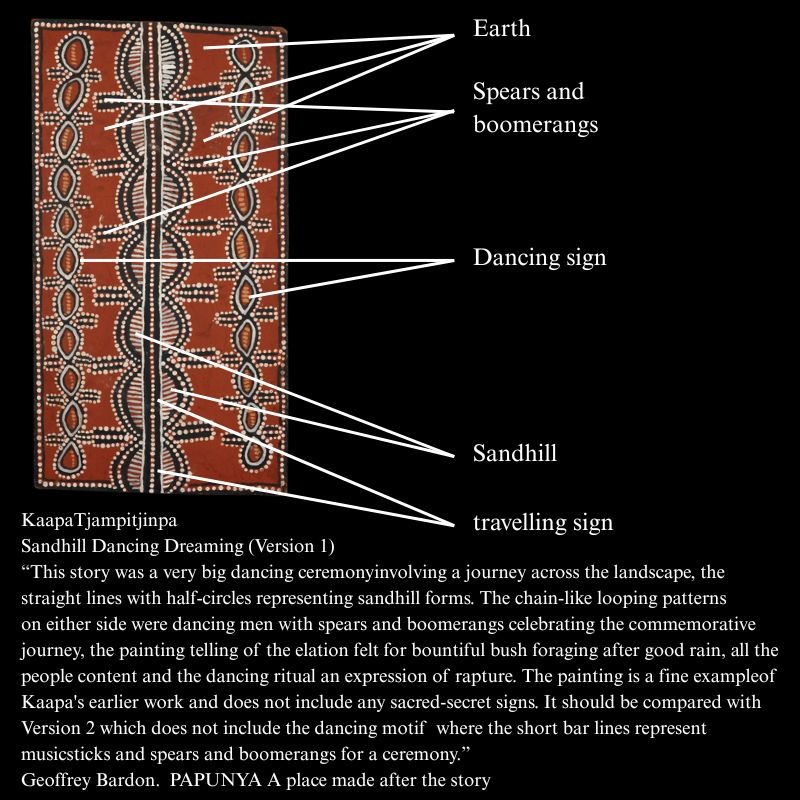

Opposite: Painting by Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa

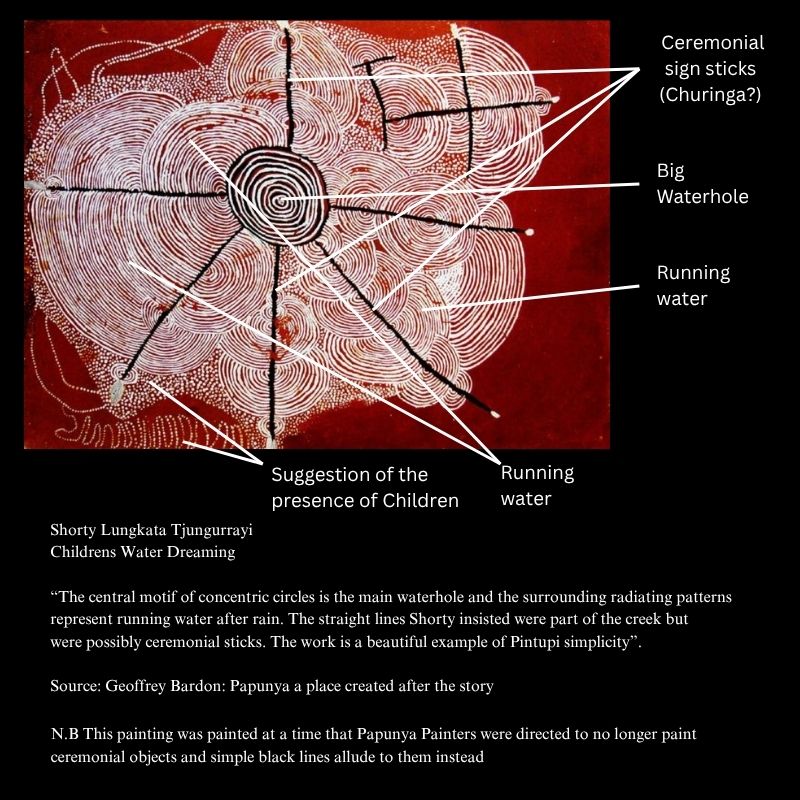

Opposite: Painting by Shorty Lungkata Tjungurrayi

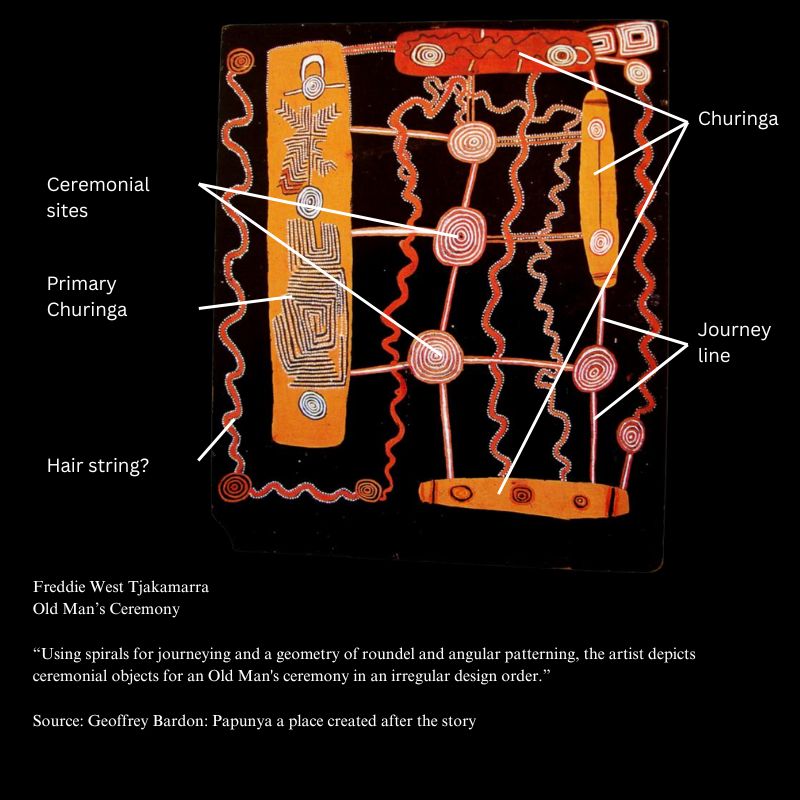

Opposite: Painting by Freddie West Tjakamarra

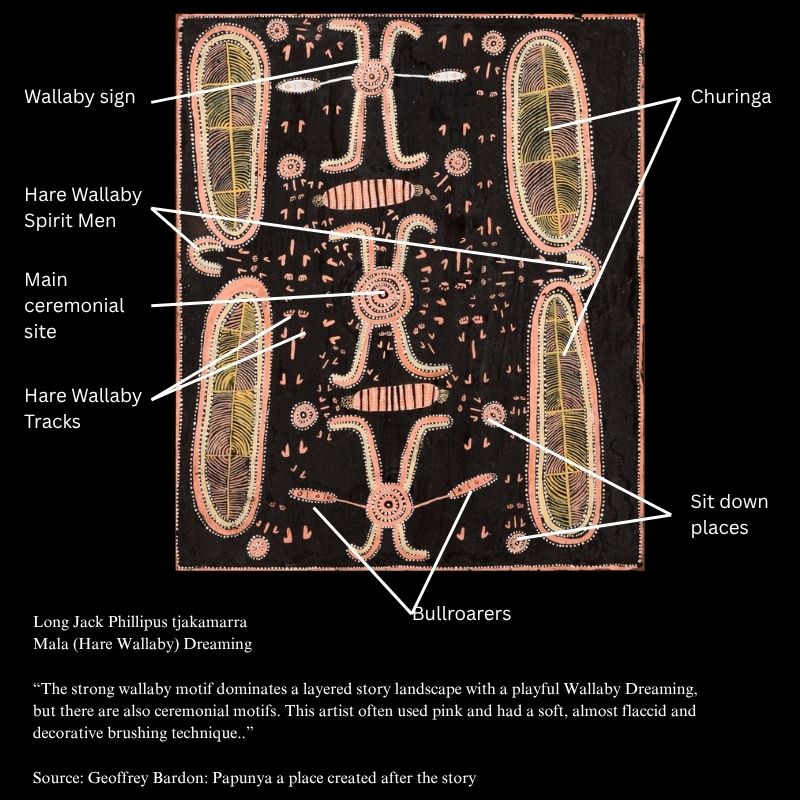

When viewing churinga in Aboriginal art remember that these are the churinga of particular people. They are the spiritual half brothers of those at ceremony and an essential part of ceremony.

Opposite: Painting by Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri

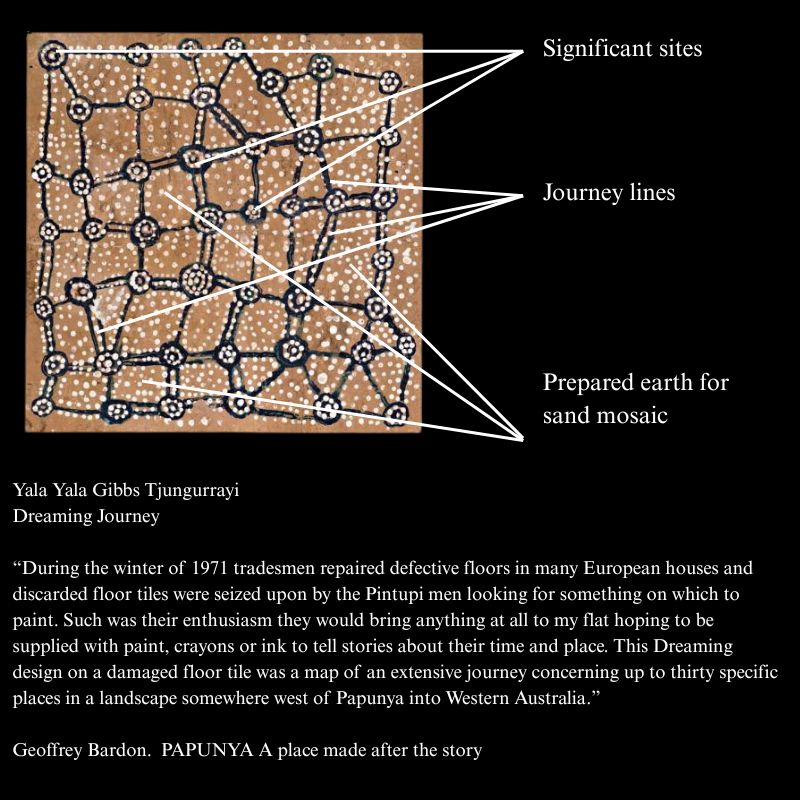

Opposite: Painting by Yala Yala Gibbs Tjungurrayi

Opposite: Painting by Charlie Tawara Tjungurrayi

Opposite: Painting by Uta Uta Tjangala

Aboriginal art meaning disclaimer

There is more to all this than I have described. I am just an ignorant European with a deep passion for aboriginal and Oceanic tribal art. There is more to all this than I can describe because the full story can only be learnt by the initiated.

No offense is meant by this post. I believe that it is only through trying to wrap our minds around other cultures belief systems can better question our own belief systems.

Other Aboriginal Art and Artists

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.