Wally Mandarrk

(c. 1915–1987)

Barabba Clan | Balang Skin Group | South-Central Arnhem Land

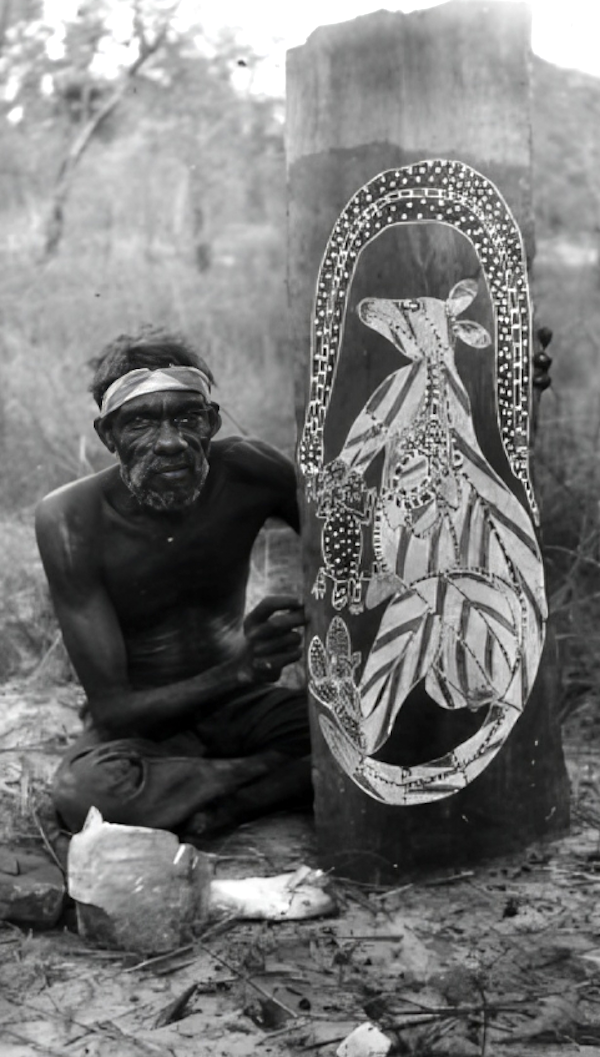

Wally Mandarrk stands as a seminal figure in the canon of classical Kunwinjku oenpelli bark painting, revered both for his fidelity to ancestral tradition and for his distinctive compositional voice. Born around 1915 in remote south-central Arnhem Land, Mandarrk lived much of his life away from European contact, choosing to remain immersed in ceremonial life and the ancestral laws of the stone country. His first known encounter with Europeans occurred in 1946, when he undertook seasonal work at a sawmill in Maranboy. Even then, he remained a man of resolute privacy and deep cultural knowledge—qualities that permeate his artistic practice.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Mandarrk resided at a number of bush camps, including Mankorlod, before founding the Yaymini outstation on his ancestral estate. A senior lawman of the Barabba clan and Balang skin group, Mandarrk was an authoritative custodian of Kunwinjku cosmology, songlines, and visual law. His works, executed on bark in natural earth pigments, are compelling for their raw integrity, their confident minimalism, and their connection to the sacred landscapes of the Arnhem escarpment.

Mandarrk painted most of his barks in the late 70’s and early 80’s. His artworks are collectable but vary considerably in value. If you want an estimate of what your Wally Mandarrk painting is worth please feel free to send me an image. I do buy Mandarrk paintings or sell them on a commission basis.

Artistic Practice and Iconography

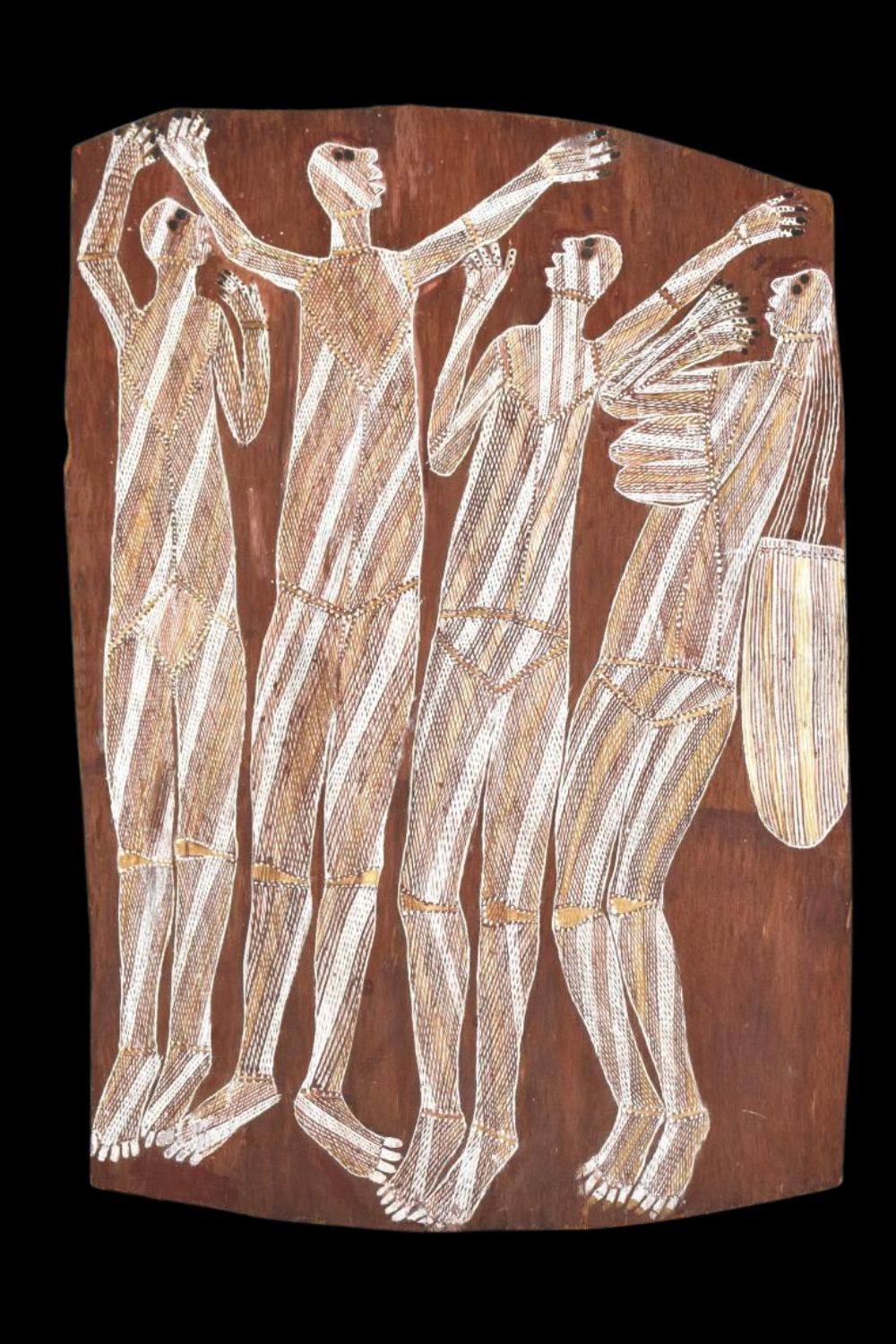

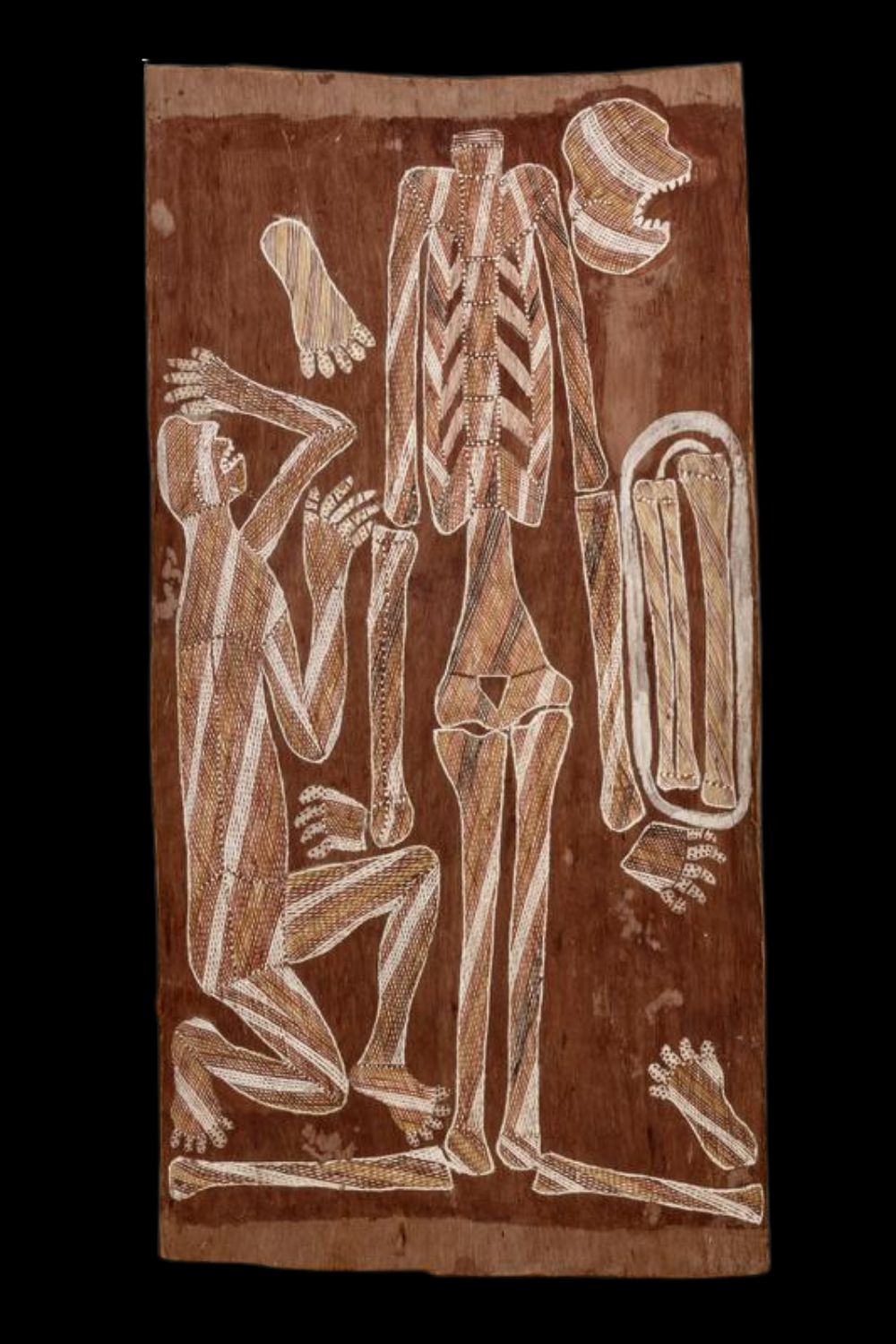

Mandarrk’s practice was defined by his unwavering adherence to traditional materials and methods. Long after other artists transitioned to synthetic adhesives, Mandarrk continued to employ djalamardi—orchid sap—as a natural binder for his ochres, imparting a matte, earthen texture to his surfaces. His figures are notable for their robust, simplified outlines and precise infill of rarrk—cross-hatching in bands of red, yellow, and white pigment, often applied with a uni-directional or vertical rhythm. Unlike the x-ray internal detailing common other artist of the region like Lofty Nadjamerrek or Dick Murrumurru, Mandarrk’s rarrk articulates the spiritual presence rather than anatomical reality of his subjects.

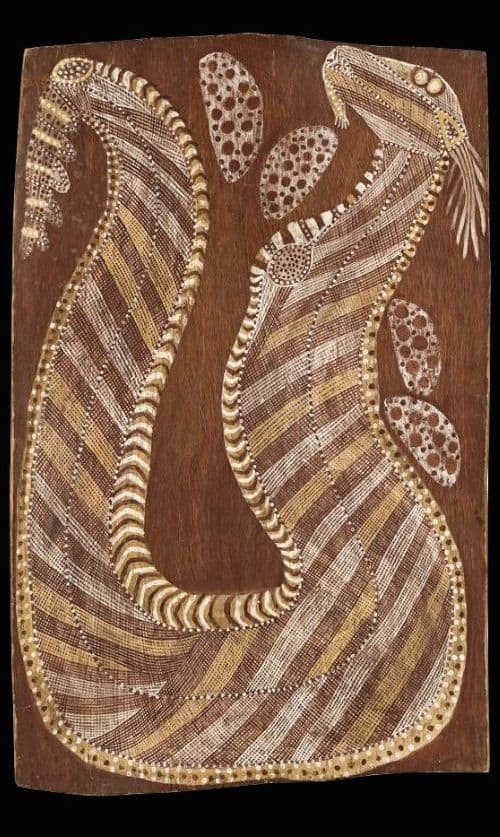

His works frequently depict Mimih spirits—elongated, mischievous beings said to inhabit the rocky escarpments—and Wayarra, ghost-like figures who serve as cautionary exemplars of improper behaviour. These spirits, integral to Kunwinjku moral storytelling, are shown hunting, carrying dilly bags, or playing the mako (didgeridoo), often in compositions that blend the sacred with the domestic. In other works, Mandarrk returns to foundational mythologies, rendering animals such as crocodiles, kangaroos, echidnas, and birds, as well as the omnipresent Bolung (Rainbow Serpent)—a creator ancestor of both generative and destructive force.

One of Mandarrk’s most iconic works, Borlung and Kangaroo (c. 1972–73), now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia, was originally painted not for market but on the wall of his family’s bark shelter at Mankorlod. It was later retrieved and preserved by Maningrida Arts coordinator Dan Gillespie. This anecdote exemplifies Mandarrk’s practice: art not as commodity, but as a continuation of lived ceremony and familial connection.

Wally Mandarrk passed away in 1987.

Market Presence and Legacy

Wally Mandarrk’s bark paintings occupy a distinct and respected position in the secondary market for Aboriginal art. His works were included in the landmark 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land and later acquired by the Maningrida Art Centre during its formative years. Institutional recognition has followed: his barks were featured in Art of Aboriginal Australia (North American tour, 1974–76), Kunwinjku Bim (National Gallery of Victoria, 1984–85), and Aratjara: Art of the First Australians (Europe, 1993–94), among others.

In the auction sphere, Mandarrk’s market trajectory reflects broader shifts in taste within the Aboriginal art market—from early enthusiasm for bark painting to a mid-2000s pivot toward Western Desert and urban expressions. He debuted in Sotheby’s first specialist Aboriginal sale in 1994 and was ranked 38th in the Aboriginal art market by 2000, according to AIAM100 data. By 2010, amid changing preferences, he had declined to 127th in ranking.

Yet the market’s recent reawakening to ethnographic depth and museum-grade provenance has restored interest in his work. In 2013, 11 works appeared at Bonhams, nearly all from the Clive Evatt Collection—only one failed to sell. That same year saw his second-highest result at auction: $6,100 AUD, eclipsed only by a 2000 Sotheby’s sale at $7,475 AUD. In 2017, Mossgreen offered five of his barks, with a strong average price of $3,802 AUD and a high of $5,208 AUD, ranking him 70th for the year among Aboriginal artists.

With over 140 works now recorded in public auction, Mandarrk remains eminently collectible, especially for connoisseurs seeking works that possess both cultural gravitas and historic authenticity. His low average price relative to desert artists offers rare accessibility, while his connection to early Arnhem Land fieldwork and pre-industry practice ensures curatorial relevance.

Conclusion

Wally Mandarrk was not merely a painter, but a transmitter of ancient law—his barks a visual archive of spirit beings, mythic animals, and sacred territories. In a market that increasingly values lineage, ethnographic resonance, and regional depth, Mandarrk’s work has renewed significance. Each piece is an encounter with a worldview scarcely touched by modernity—rich in spirituality, elegantly composed, and materially grounded in the land itself.

For discerning collectors, Mandarrk’s paintings offer more than aesthetic value—they are time-carved statements of Arnhem Land culture, still echoing with the authority of a senior ceremonial man.

The Rainbow Serpent

Aboriginal people believe that Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent, created many sacred sites in Arnhem Land. Characteristics of Ngalyod vary from group to group and also depend on the site. He can change into a female serpent, and has both, powers of creation and destruction. Ngalyod is most strongly associated with rain, monsoon seasons, and the rainbows that arc across the sky like a giant serpent. He is most active in the wet season. In the dry season, he rests in billabongs and freshwater springs. When he rests he handles the production of water plants such as waterlilies, vines, algae, and cabbage tree palms.

When waterfalls roar down deep gorges, that Ngalyod is calling out. Large holes in stony banks of rivers and cliff faces are his tracks.

The rainbow serpent is deeply respected because it will swallow people who offend him. If Ngalyod swallows people during floods that he has created, he regurgitates them and they transform into new beings by his blood.

Aboriginal people respect sacred sites where the Rainbow Serpent resides. Near these sites, cooking is not allowed. Cooking near the resting place of the great serpent will incur his wrath. Ngalyod can cause sickness, accidents, and great floods, which make it easier for him to swallow his victims.

Although Ngalyod is generally feared throughout Stone Country, he is a friend and protector of the tiny Mimih Spirits.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Oenpelli Art and Artist Articles

Top Questions about Wally Mandarrk answered

Who was Wally Mandarrk?

Wally Mandarrk (c.1915–1987) was a renowned Aboriginal bark painter from south-central Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia. A member of the Barabba clan and the Balang skin group of the Kunwinjku people, Mandarrk lived a traditional life and became known for his deeply spiritual bark paintings that reflect ancient Aboriginal stories, ancestral beings, and the sacred connection to Country.

Where was Wally Mandarrk born?

Wally Mandarrk was born around 1915 in the remote stone country of south-central Arnhem Land, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. He later lived and worked across sites including Marlkawo, Mankorlod, and Yaymini outstation.

What kind of art did Wally Mandarrk create?

Wally Mandarrk created traditional Aboriginal bark paintings using ochre pigments and natural binders. His works feature ancestral spirits, such as Mimih and Wayarra, along with native animals and creator beings like Bolung (Rainbow Serpent). His style is characterized by stocky, simplified figures, rarrk (crosshatching) in red, white, and yellow, and a plain red background.

What materials did Wally Mandarrk use in his bark paintings?

Mandarrk used natural ochres and djalamardi—orchid juice from Dendrobium species—as a traditional binder. Unlike many artists who adopted synthetic glues, Mandarrk remained committed to ancient techniques, making his works rare and culturally significant.

What are Mimih and Wayarra spirits in Mandarrk’s art?

Mimih spirits are thin, elusive ancestral beings believed to inhabit rock crevices in Arnhem Land. They are central to Kunwinjku mythology and are thought to have taught Aboriginal people important bush survival skills.

Wayarra, on the other hand, are ghost spirits—mischievous or dangerous beings often associated with morality tales or taboo places. Mandarrk frequently depicted both, integrating cultural knowledge into visual form.

Where can I see Wally Mandarrk’s artwork?

Wally Mandarrk’s bark paintings are held in several major collections, including:

- National Museum of Australia

- National Gallery of Victoria (NGV)

- Maningrida Arts & Culture Collection

- Museums from the 1948 American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land

His work has also been shown in landmark exhibitions such as Power of the Land, Kunwinjku Bim, and Aratjara – Art of the First Australians.

How much is a Wally Mandarrk painting worth?

Prices for Wally Mandarrk’s bark paintings typically range between AUD $2,000 and $5,000, with a record auction price of $7,475 (set in 2000). His works remain affordable and collectible, especially for buyers interested in early bark traditions and authentic Aboriginal art.

Has Wally Mandarrk’s art been sold at auction?

Yes. Wally Mandarrk was featured in Sotheby’s first Aboriginal art sale in 1994. Since then, his works have appeared at major auction houses including Sotheby’s, Bonhams, and Mossgreen. A highlight was the 2013 sale of the Clive Evatt Collection, where 10 of 11 Mandarrk works sold, including one at $6,100, his second-highest price to date.

What makes Wally Mandarrk’s art important?

Mandarrk’s work is valued for its ethnographic authenticity, spiritual resonance, and use of traditional techniques. His paintings preserve sacred stories and ancestral knowledge passed down through oral tradition. As one of the earliest bark painters to be widely collected, his legacy bridges pre-contact culture and the modern Aboriginal art movement.

When did Wally Mandarrk die?

Wally Mandarrk passed away in 1987, having witnessed the early stages of the Aboriginal art industry. His work today stands as a vital record of pre-commercial bark painting practices.

Can I buy Wally Mandarrk bark paintings?

Yes. While no longer producing work, Wally Mandarrk’s paintings regularly appear in the secondary market and are available through auction houses, private dealers, and specialized Aboriginal art galleries. His works are highly collectable for their affordability, rarity, and cultural integrity.

What is Wally Mandarrk’s legacy in Australian Aboriginal art?

Mandarrk’s legacy is that of a cultural custodian and master of Kunwinjku bark painting. He represents the continuity of ancient Aboriginal storytelling, executed in a medium that remains sacred and powerful. His work is studied in both art historical and anthropological contexts and is essential for understanding the development of 20th-century Aboriginal visual culture.