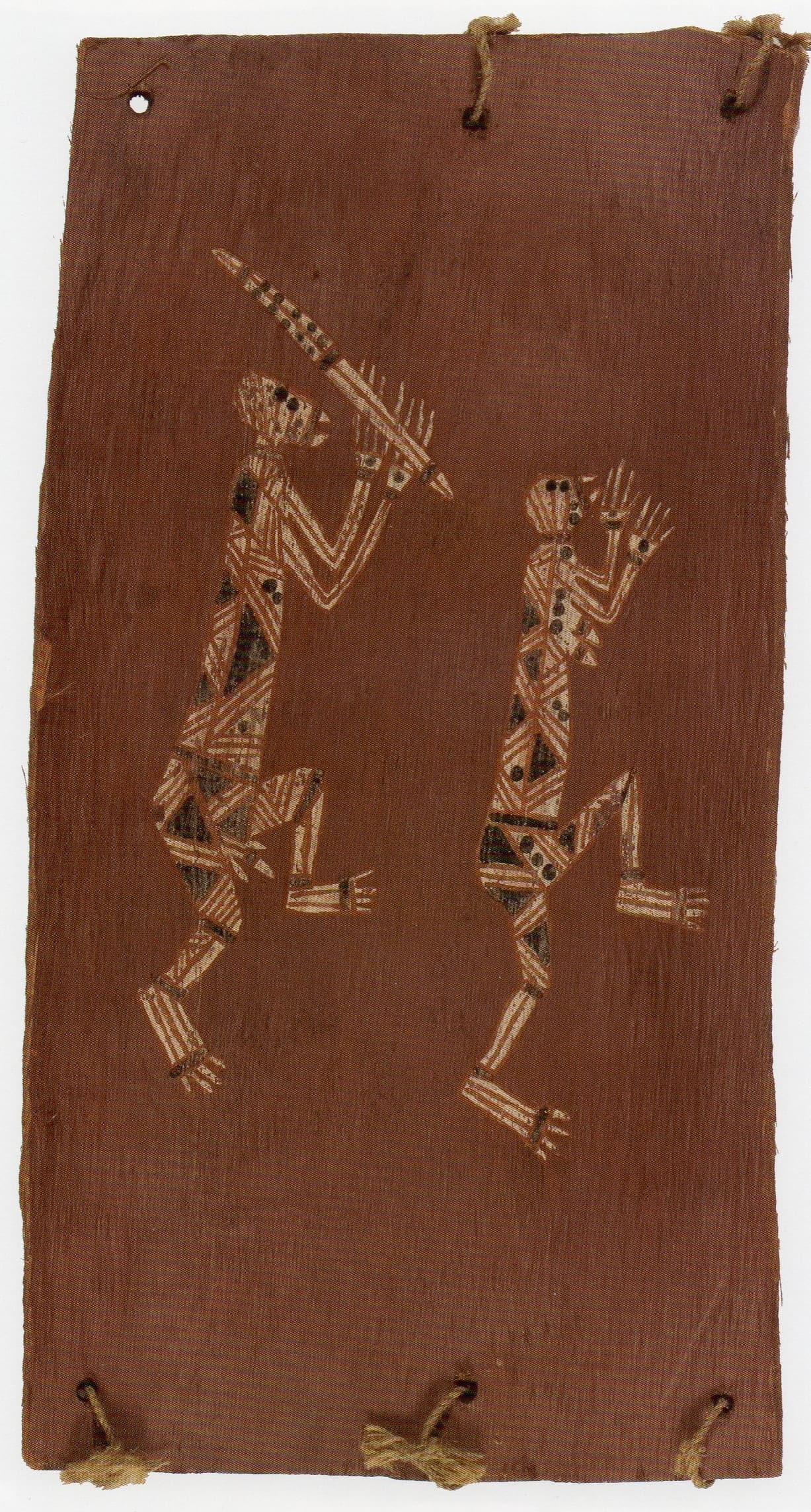

Spider Nabunu Early Oenpelli Artist

Spider Nabunu was an early Oenpelli Bark painting artist. The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their aboriginal bark painting is by Spider Nabunu. It compares examples of his work.

If you have a Spider Nabunu bark painting to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your bark painting is worth to me please feel free to send me a Jpeg because I would love to see it.

Spider also painted rock shelters along with other early Oenpelli artists like Nym Djimungurr, Najombolmi and Diidja.

Style

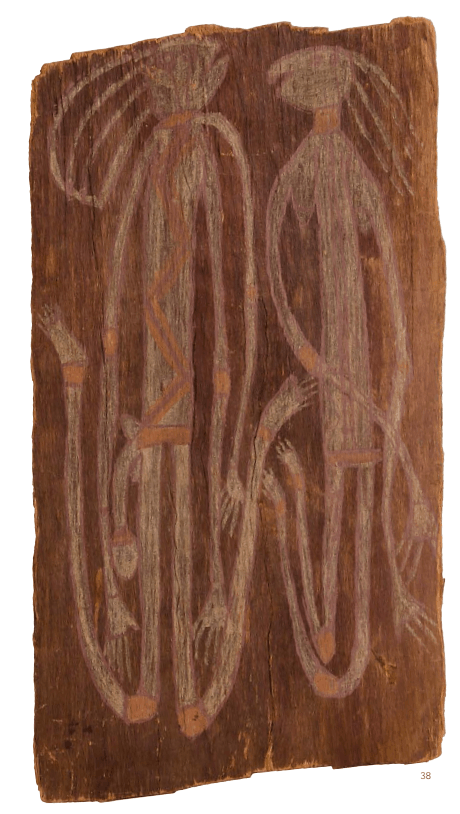

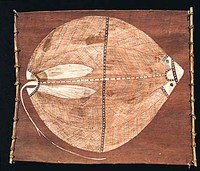

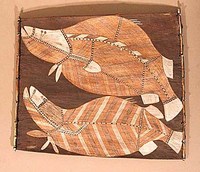

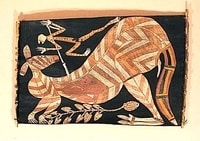

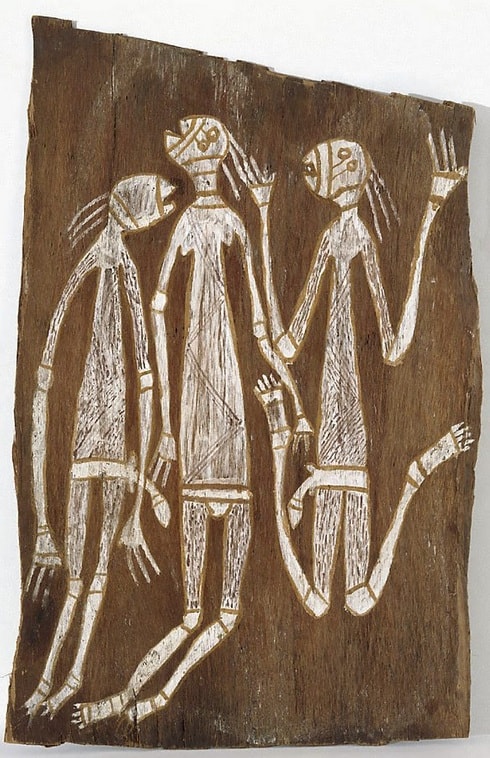

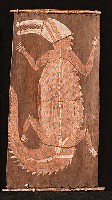

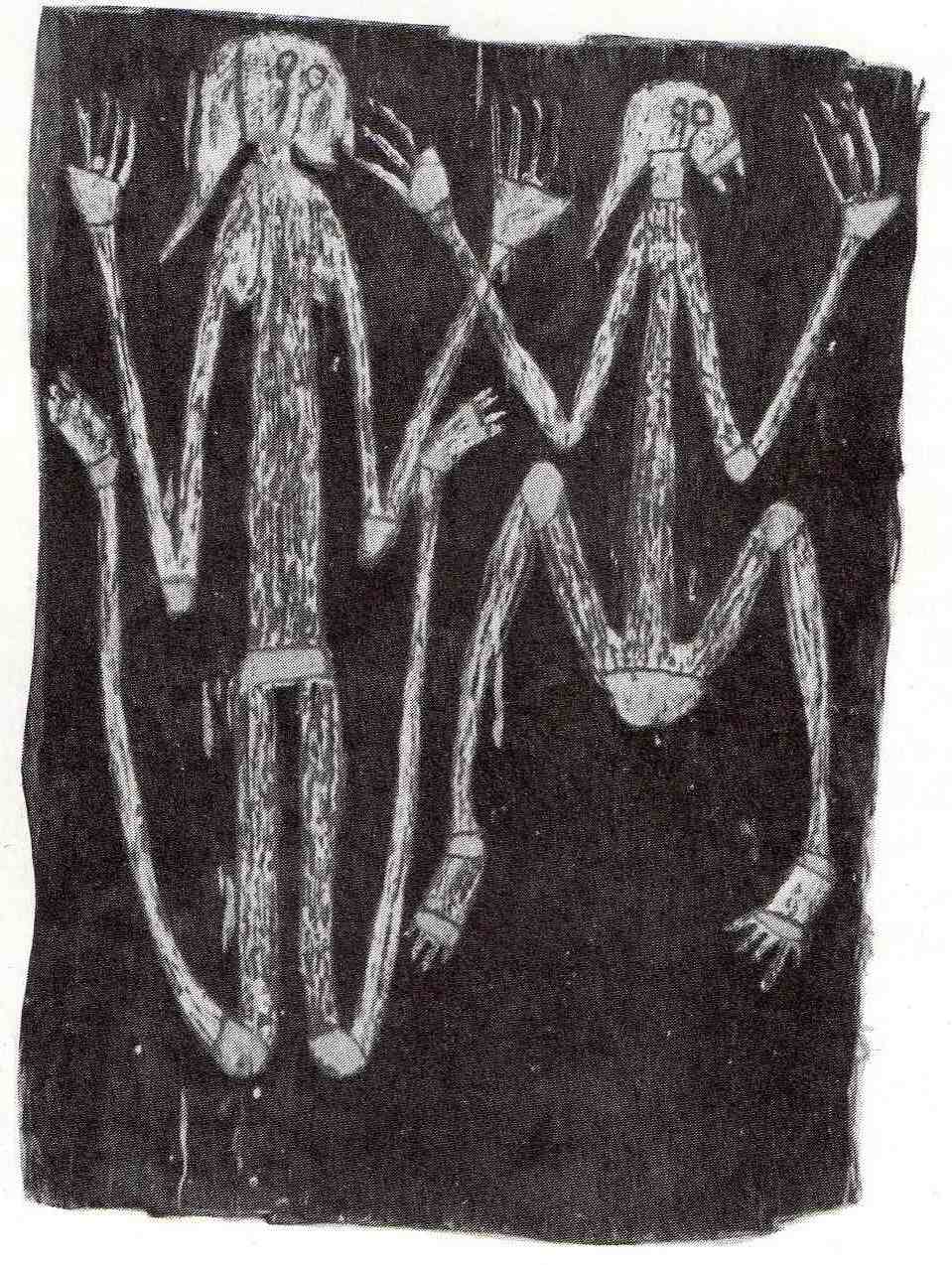

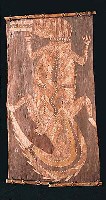

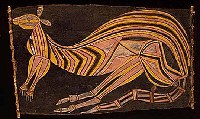

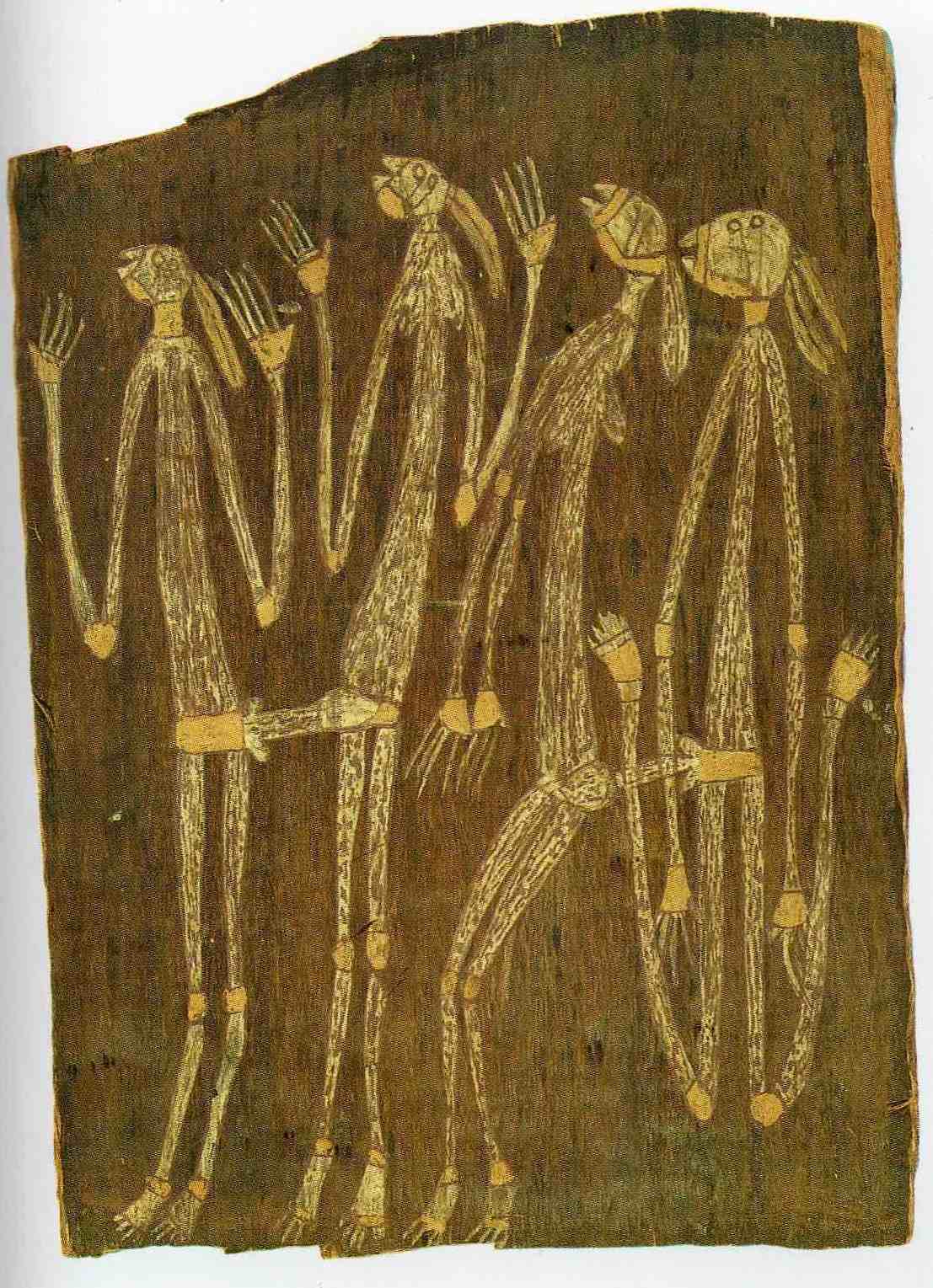

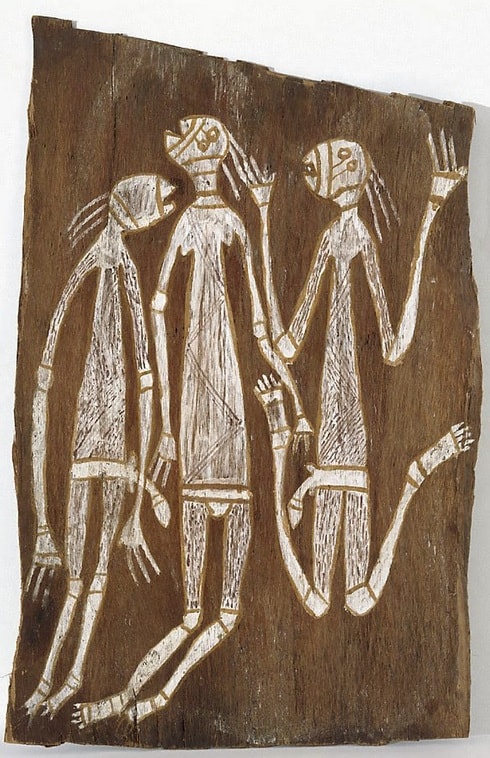

Spider Nabunu painted bark painting in an archaic style full of power and spirituality. He deserves to be recognized as an important early artist. Many of his barks have irregular edges and an early collection date. He died just as barks were being commercially collected which accounts for why so few of his works are around. His older barks deal with figures from the spirit world called Mimih. Mimih are a playful but potentially dangerous spirits of the stone country. The fluidity of his Mimih figures are like bark paintings from Crocker Island.

He tended to paint on a brown red background with figures in white detailed in red and yellow. His work exhibits a freedom and flow that I find highly desirable in a great bark painting. His early paintings show genitals and a freedom of pre-mission work. They relate to the myth of the tempted one.

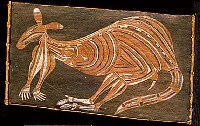

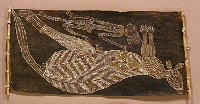

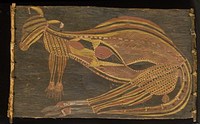

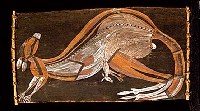

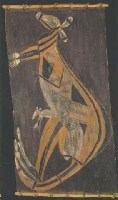

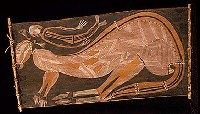

Spider’s later works are more commercial and are predominantly of animals. His animal barks include Kangaroos, crocodiles, snakes, birds, barramundi, and rays. These barks are squarer and have stick supports.

Spider’s barks have been wrongly attributed to crocker island artists including Namatbara. MidjauMidjau and even Nangunyari.

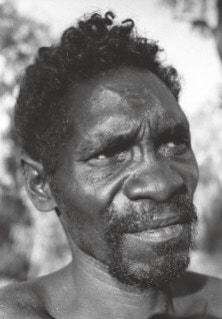

Biography

Spider Nabunu was born around 1924 and died in 1973. He was a painter of rock shelters as well as barks.

Skin: Nawamud / Gojok.

Clan: Bulardja.

Languages: Kunwinjku, Kune, Dalabon, Gunjeihmi, Kundedjnjenghmi.

Djang/ dreaming: Namarrkon (lightning man).

Kunred / Country: Yiminy

Traditional roles and responsibilities: sorcerer, healer, head hunter, and artist. Ceremonial leader of Gunapipi, Mardyin, and Djabulurrwah ceremonies.

Mission based occupations: meatworker, buffalo hunter, baker and public servant.

Spider had five wives. His wife Daisy Guymala had three children Betty, Bundy, and Olive. His second wife Molly Nabarlambarl had one child Leanne. The third wife Wendy Djogiba had one child Mary. Spiders fourth wife Dukalwanga Namundja had one child Ivan Namirrki. His last wife Ruth Djandjomerr had three children Neville, Robert and Ivan Namarnyilk.

Special Thanks to Bindi Isis (Artist, activist, naturalist, teacher, mother). She provided biographical information about this fascinating Man.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Western Arnhem land Artists and Artworks

Spider Nabunu Bark painting Images

The following images are not a complete list of the artist’s works but give some idea of his style and variety.