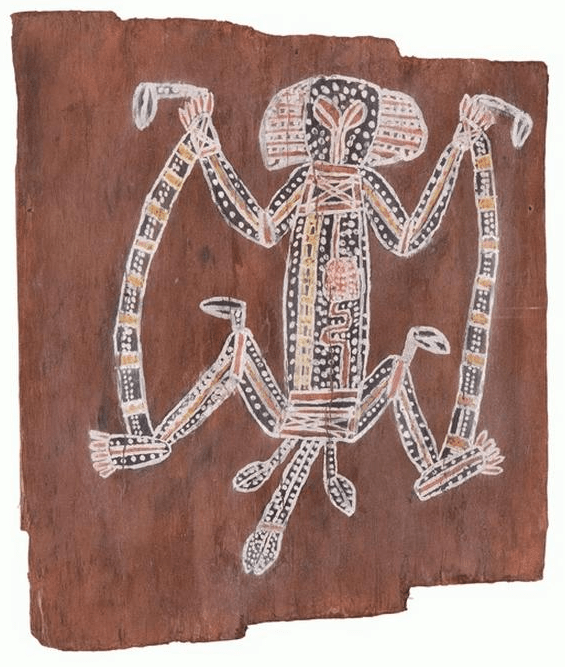

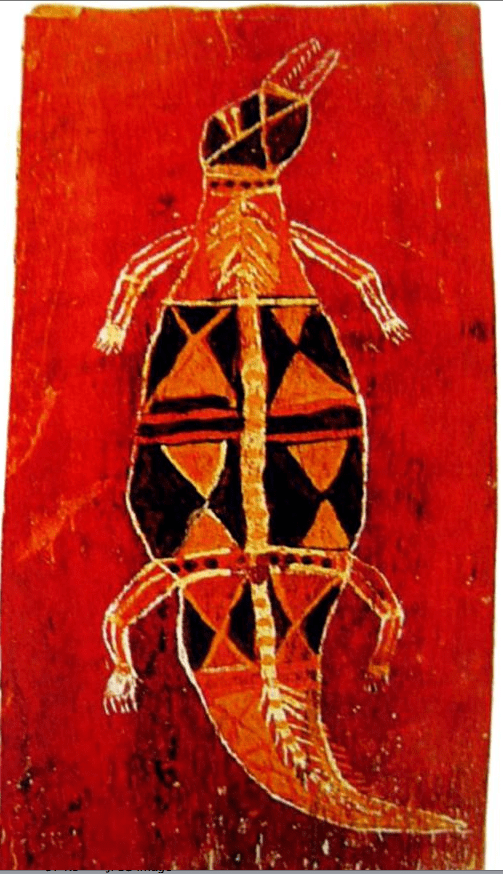

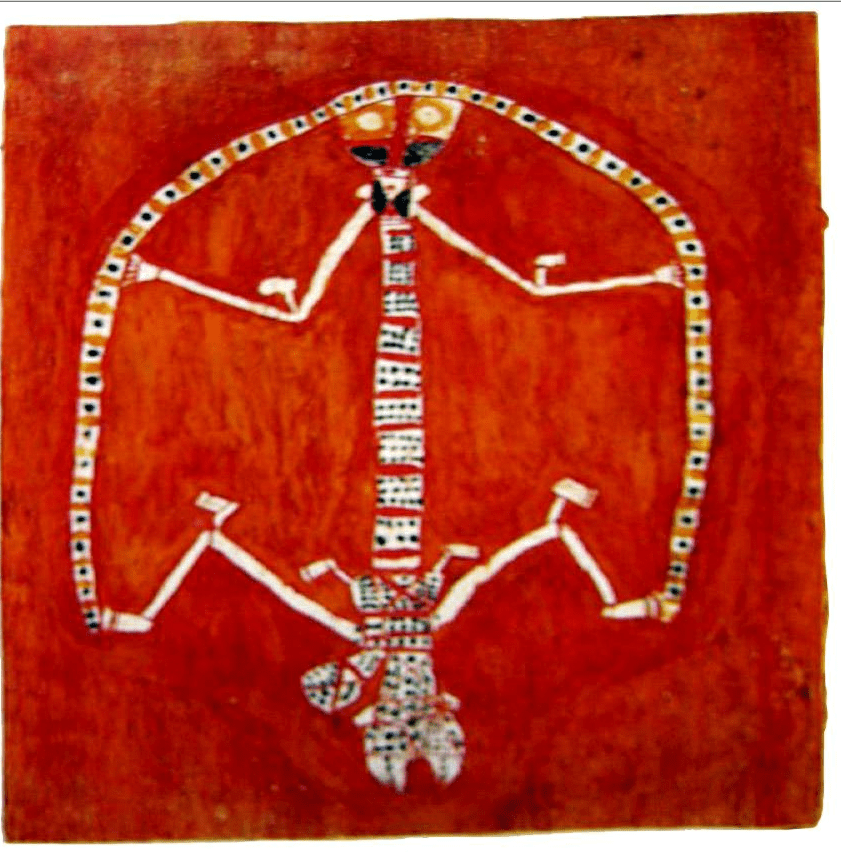

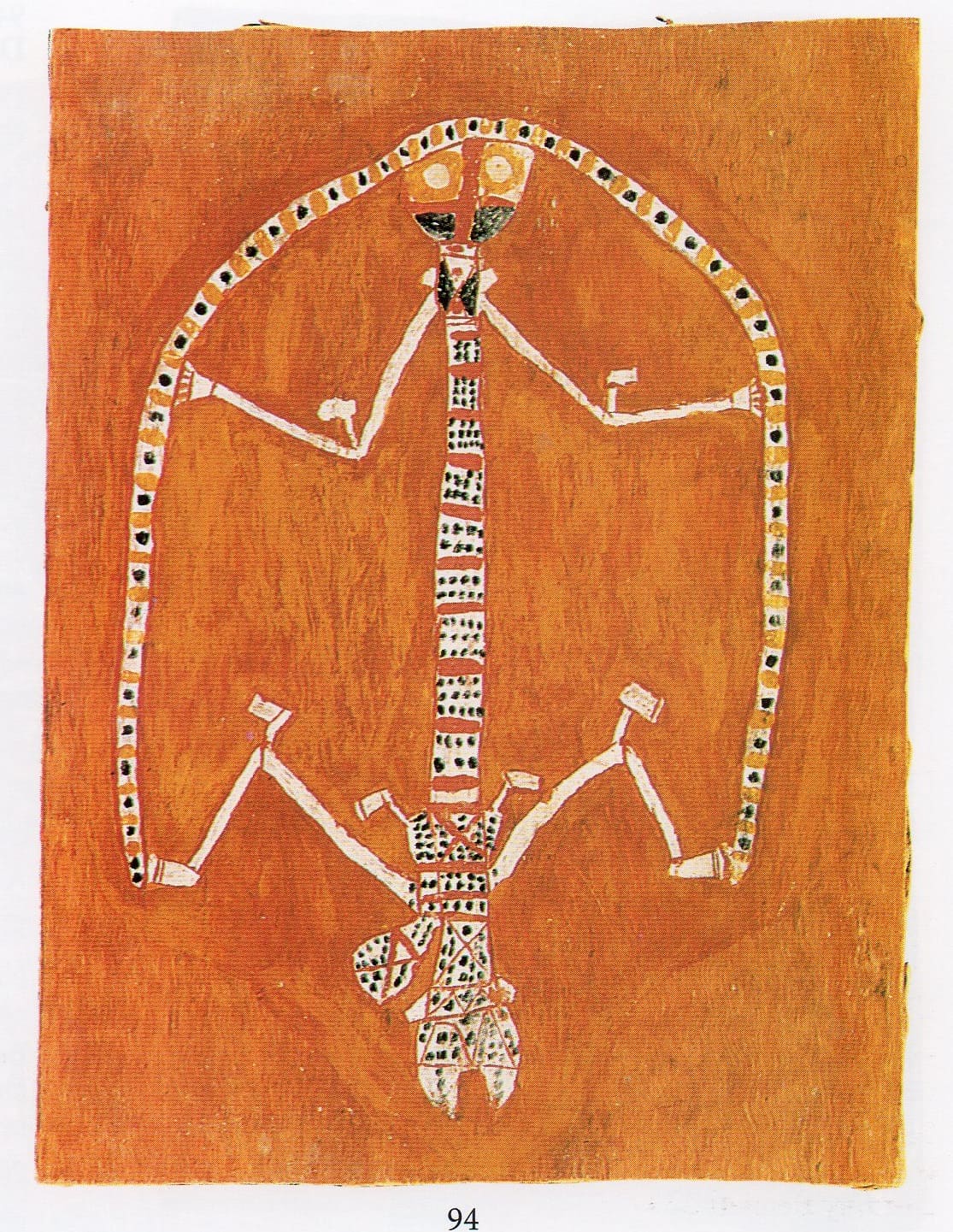

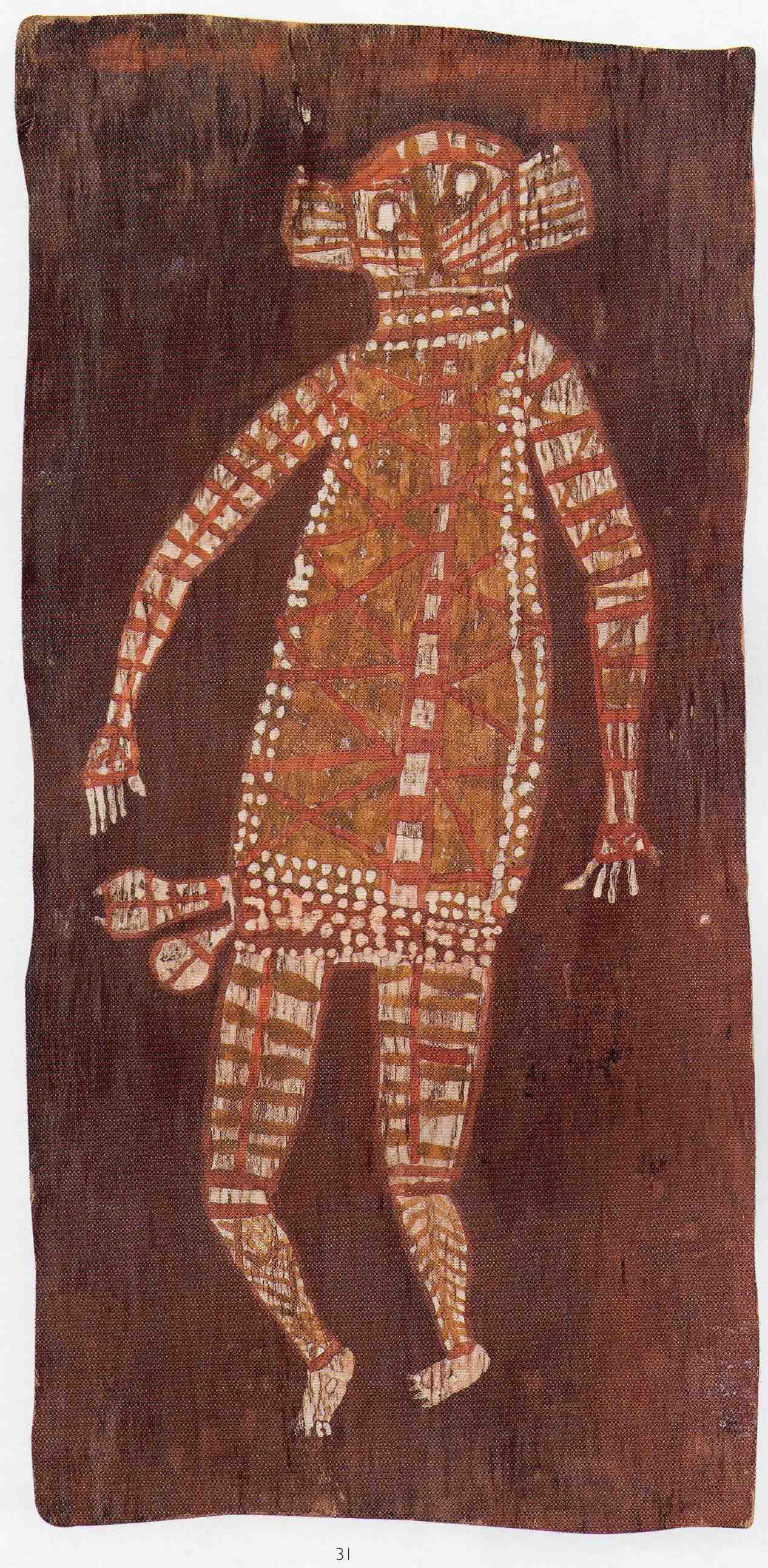

Nym Djimurrgurr master of the Namarrkon

Nym Djimurrgurr is an extremely traditional Bark painter from the Oenpelli Region. His Barks often depict images of the thunder god and have a real archaic power to them.

The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their aboriginal bark painting is by Nym Djimurrgurr. It compares the few known examples of his work.

If you have a Nym Djimurrgurr bark painting to sell please contact me. If you just want to know what your bark painting is worth to me please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

Style

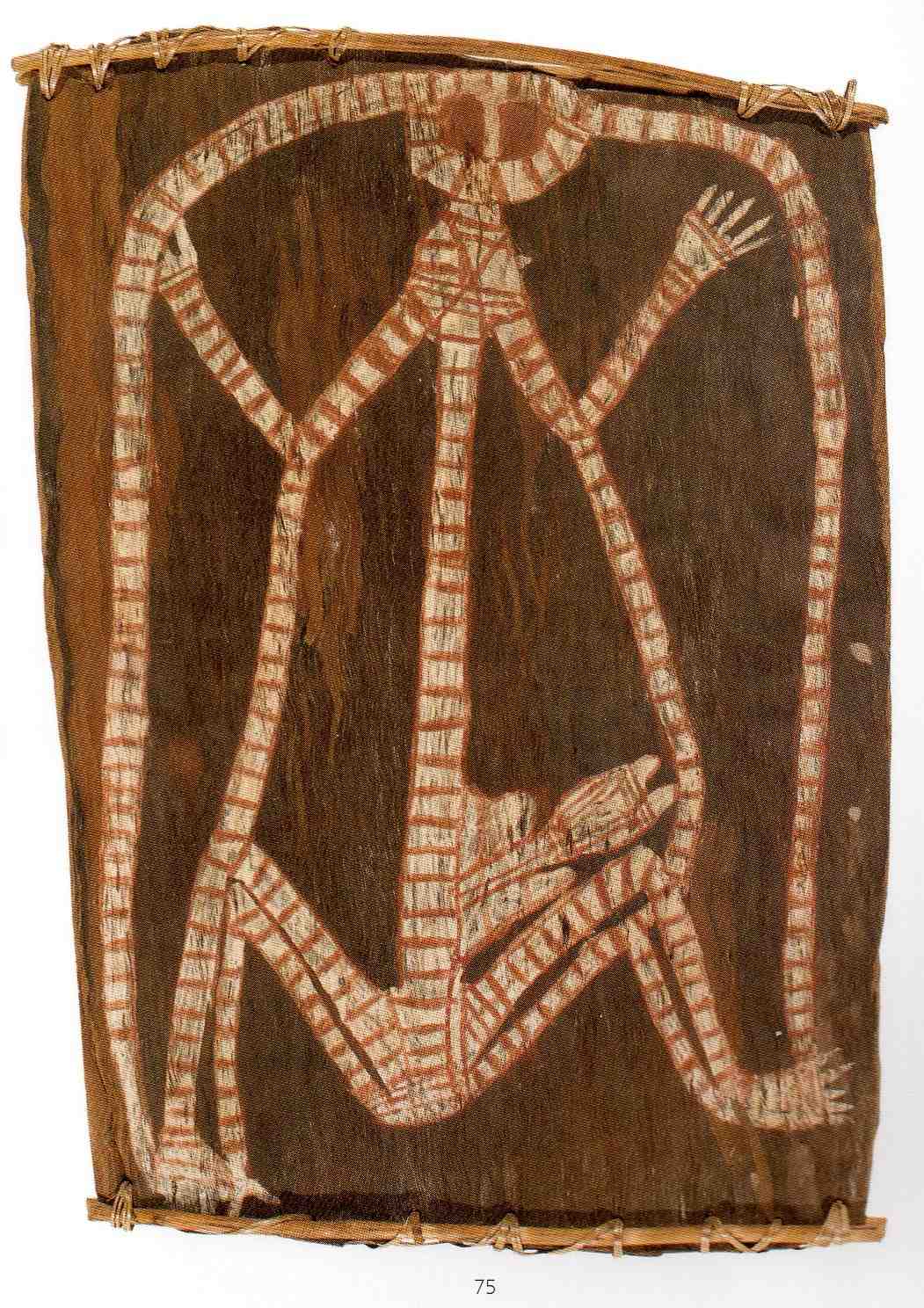

Nym Djimurrgurr painted bark paintings in an archaic rock shelter style. He is best known for his excellent depictions of the lightning spirit. His depictions are so close to those found in rock shelters because he came from a rock shelter painting background. Nym figures are often simple with vastly exaggerated genitals. His barks have a monotone background and his best early works do not use cross-hatching.

Namarrkon is the Lightning Spirit that lives above the clouds. It causes the intense electrical storms of Kunemeleng, the pre-wet season. The Spirit is in the rock art and bark paintings of the region with a circuit of lightning encircling its body. Stone axes are shown protruding from his arms, legs.

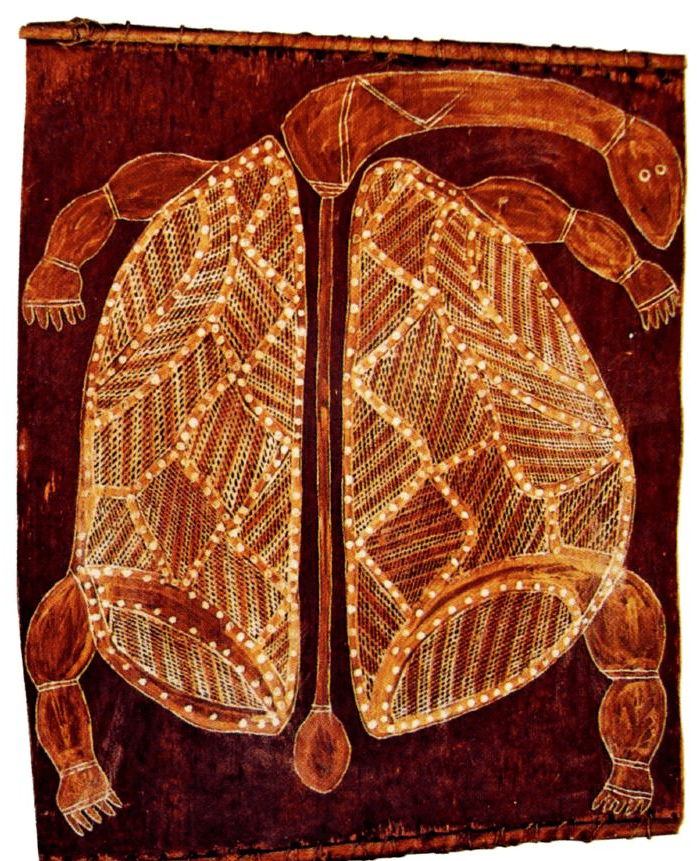

Nym Djimurrgurr depictions of totemic animals are not nearly as collectible. They have a more commercial feel to them. They lack the raw energy of his figurative works.

His works can be compared to other early Oenpelli artists like Najombolmi and Mandidja

Biography

Along with many other Arnhem Land Artists who did bark paintings, there is not a lot of information readily available about Nym Djimurrgurr . If anyone knows more information about the biography of Nym Djimurrgurr, please contact me as I would like to add it to this article.

Care for Aboriginal Bark Painting by ensuring it always stays dry and does not move as ochres can flake off. A bark painting is best stored in a dust-free place and away from insects.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Western Arnhem land Artists and Artworks

The following images are not a complete list of the artist’s works but give some idea of his style and variety.