The Wandjina: Spirit Ancestors of the Kimberley

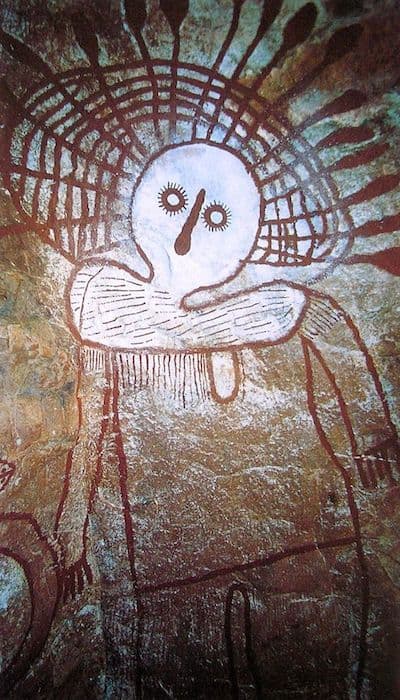

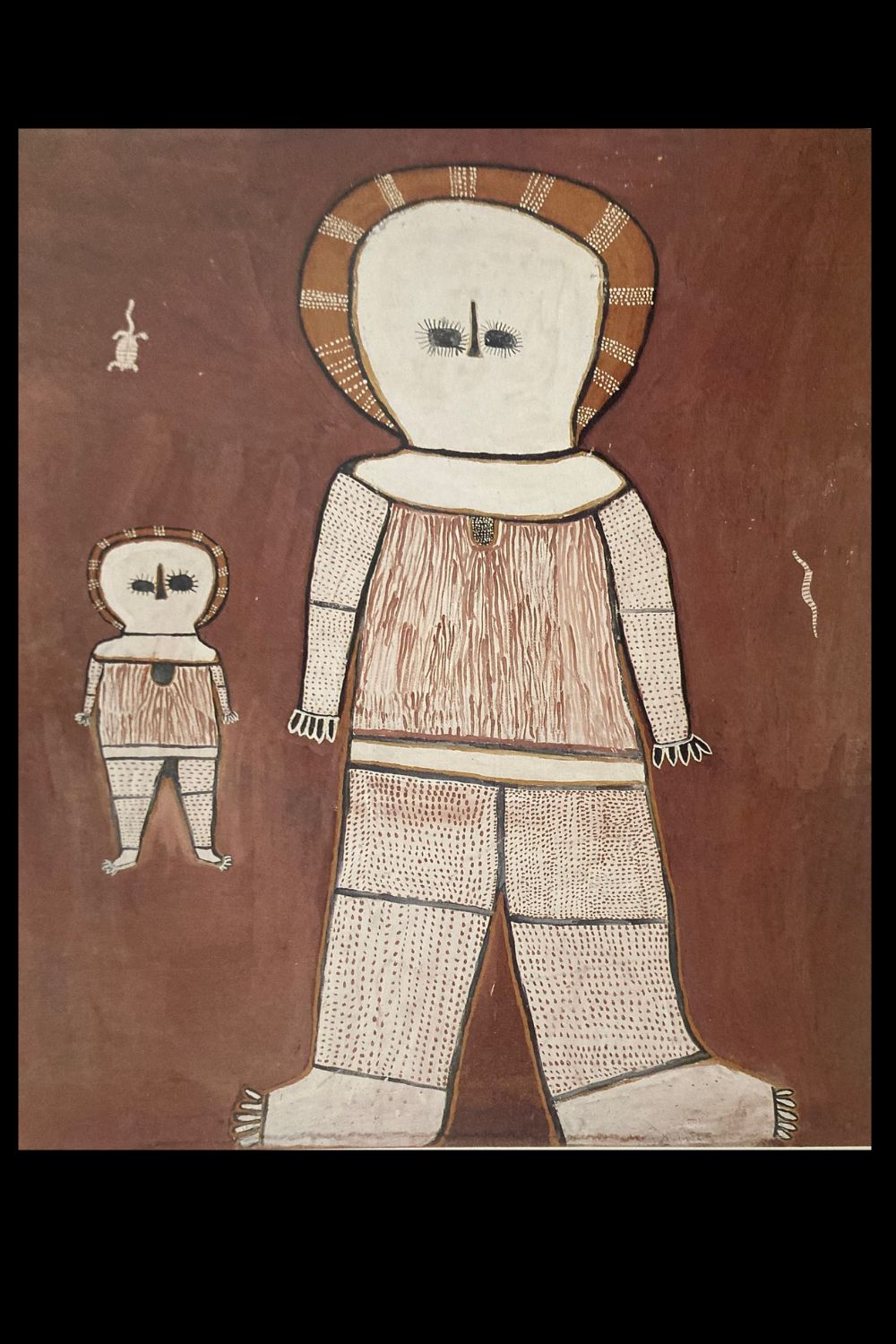

Few cultural expressions in Australia match the enduring power and mystique of the Wandjina (also spelt Wondjina or Wanjina) the iconic spirit beings of the north-western Kimberley region of Western Australia. These awe-inspiring ancestral figures, painted on rock shelters for millennia, form one of the most spiritually charged and visually compelling traditions of Aboriginal rock art anywhere in the world.

While the Rainbow Serpent (Ungud/Galeru) appears widely across the continent, the Wandjina are uniquely Kimberley. These monumental mouthless beings are specific to the Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal peoples—who maintain custodianship over the sacred rock galleries scattered across their clan estates, or dambun. In recent years, Wandjina paintings have transcended their localised origins, becoming global icons of Australian Indigenous art.

This article focuses on Wandjina but is accompanied by another article that examines the history of commercial Wanjina painting and major Wandjina painters.

If you have a Wandjina painting on Bark, Canvass or composite board or even cardboard to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your Wanjina painting is worth to me please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

What Is Wandjina Art?

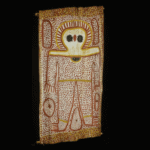

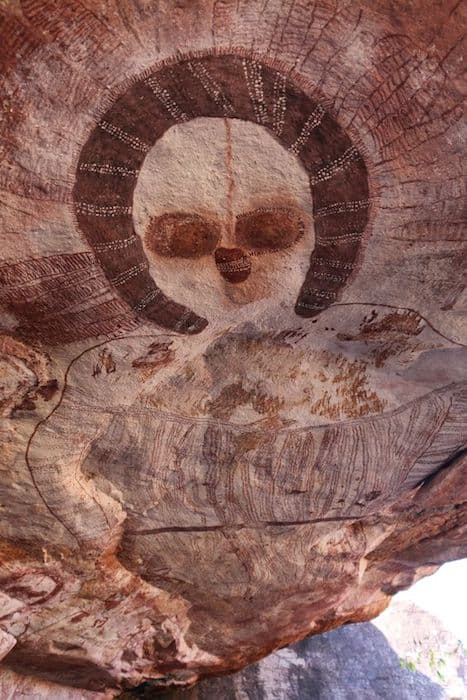

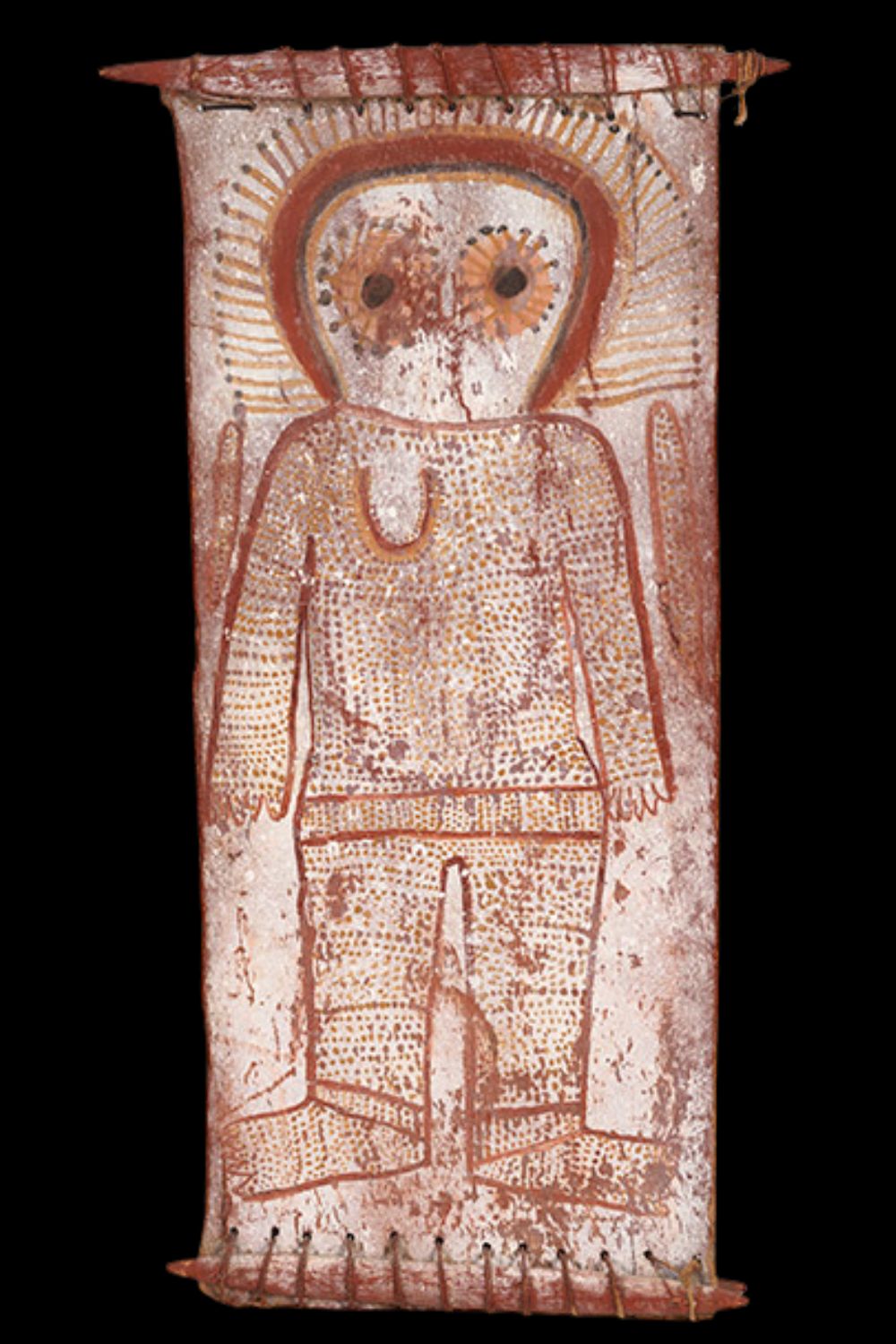

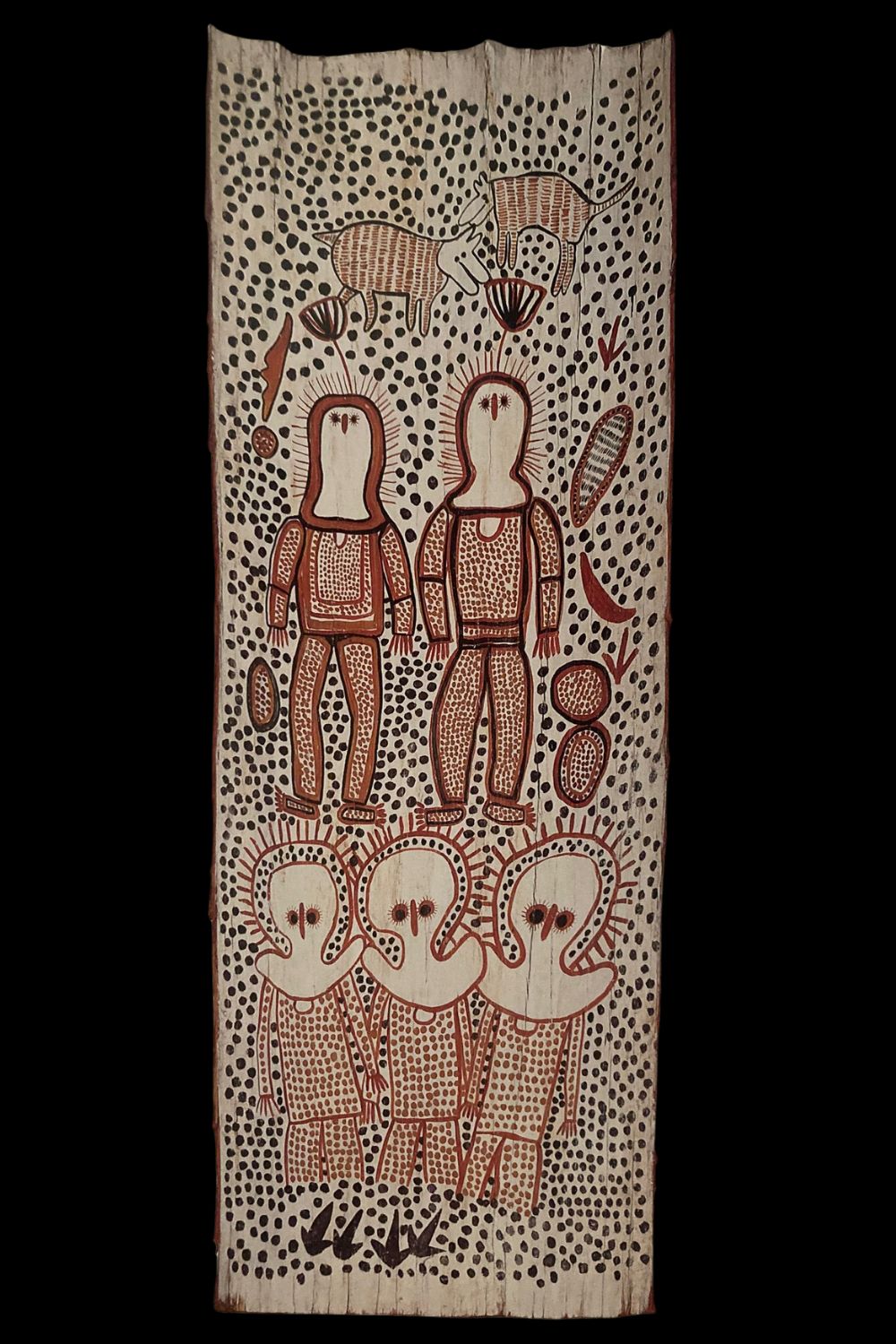

Wandjina art refers to the ancestral figures painted in rock shelters across the northwest and central Kimberley. These figures are characterised by their frontal symmetry, strikingly large faces, halo-like head decorations, and lack of mouths—features laden with symbolic and mythological meaning. The Wanjina are painted using ochres—white huntite white clay pigment forming the background, with red, yellow, and black used for detailing.

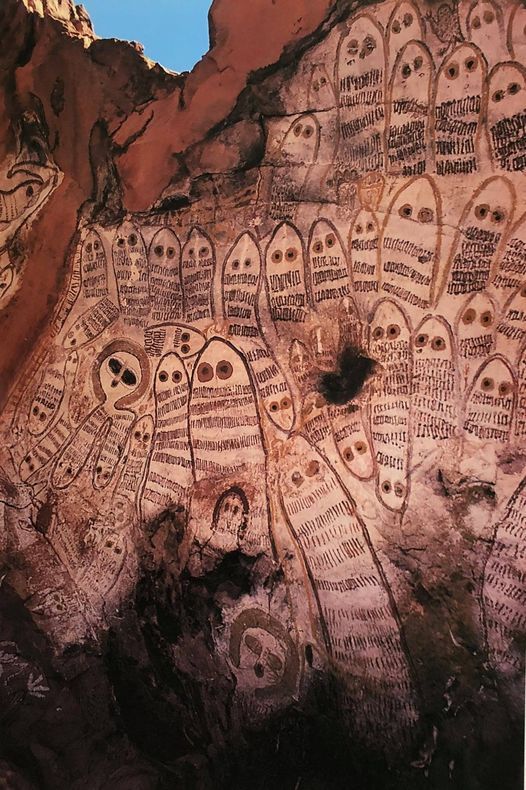

They are often accompanied by Rainbow Serpents, totemic animals, or other spirit figures such as Ngarra Ngarra(honey spirits), all part of a richly interconnected visual cosmology.

Unlike many forms of Aboriginal art that evolved with outside influence, Wandjina paintings are unbroken ceremonial traditions, regarded not as human creations but as literal manifestations of the ancestral beings themselves. According to belief, when a Wondjina completed its earthly journey in the lalai (Dreaming or creation time), it laid down in a rock shelter and became part of the earth—its body becoming the painting, its spirit continuing in the landscape.

The Meaning of the Wandjina: Spirit Ancestors and Rainmakers

The Wandjina are ancestral spirits and rainmakers, deeply embedded in the cosmology and environmental cycles of the Kimberley. Their presence ensures the fertility of the land, the reproduction of plants and animals, and the seasonal arrival of monsoonal rains. This spiritual custodianship is maintained through re-touching ceremonies, which regenerate both the paintings and the natural world.

Mouthless and silent, the Wanjina command respect. In some traditions, their mouths were sealed by the Rainbow Serpent to prevent them from speaking and causing torrential rain. In others, they pressed their lips shut upon the first lightning strike, never to open again. Their large, staring eyes—often likened to owls—symbolise an all-seeing presence, watching over country.

Wandjina Rock Art Sites: Sacred Spaces of Ancestral Power

Each Wondjina rock art site corresponds to a particular family or clan estate. These galleries are living ceremonial spaces, not passive remnants of the past. They serve as increase centres for natural resources, and in many cases, as ancestral burial grounds—sites where human bones were once placed, where spirits return to rest, and from where new spirit children may emerge.

When George Grey, the British explorer, first encountered Wanjina paintings near the Glenelg River in 1837, he was astounded by their scale and otherworldly presence. His sketches sparked widespread speculation—were they Egyptian? Phoenician? Alien?—all while ignoring the deep cultural authority of the people who made them. Only later, through researchers like J.R.B. Love and A.P. Elkin, did the world begin to understand their true Indigenous origin.

The Conservation of Wandjina Rock Art

The relocation and displacement of Worrorra, Ngarinyin and Wunambal peoples during the mission era disrupted the sacred responsibility of repainting Wandjina figures. Without periodic re-touching ceremonies, many of the original paintings have suffered degradation—particularly because the white mineral base, huntite, is chemically unstable in humid environments.

However, the reawakening of cultural pride and the efforts of artists like Charlie Numbulmoore in the 1960s and contemporary cultural leaders such as Donny Woolagoodja and his father Sam Woolagoodja, have led to renewed stewardship of these sacred images. Their legacy ensures that Wandjina art, both ancient and contemporary, remains a central pillar of Kimberley Aboriginal identity.

The controversial 1987 repainting of sacred rock sites near Mount Barnett—carried out without the consent of traditional custodians—underscored the delicate balance between preservation and desecration. Eight sites were overwritten with inauthentic imagery, raising urgent questions about cultural stewardship.

The Wandjina and the Rainbow Serpent (Ungud/Galeru)

The Wanjina do not act alone. They are inextricably linked to the Rainbow Serpent, known locally as Ungud or Galeru, depending on region. Where Wandjina are anthropomorphic, Ungud is serpentine—a vital creative force associated with water, fertility, and the creation of spirit children.

In the Mandagnaardi site, near Gibb River Station, a dramatic panel of 42 Rainbow Serpent heads represents a family of serpents: father, mother, and 40 offspring. Tucked among them are two small Wondjina figures—underscoring the collaborative spiritual work of these beings. Their intertwined power governs the natural world and ensures the continuity of life.

Why Are There So Many Wandjina in One Place?

Aboriginal life is communal, and so are Wandjina compositions. Rock shelters typically feature clusters—or “mobs”—of Wandjina, male and female, surrounded by other beings from the Dreaming. These groupings echo ceremonial gatherings, family ties, and the interconnectedness of spirit and country. The Wiwilunggu site, as painted by Jack Wheera, illustrates this beautifully, with Wondjina surrounded by yams, bird tracks, and dingo motifs—each element reinforcing the songlines and ecological knowledge embedded in the landscape.

Wandjina Paintings on bark and board

Wandjina Painting: From Rock to Bark and Board in the Kimberley

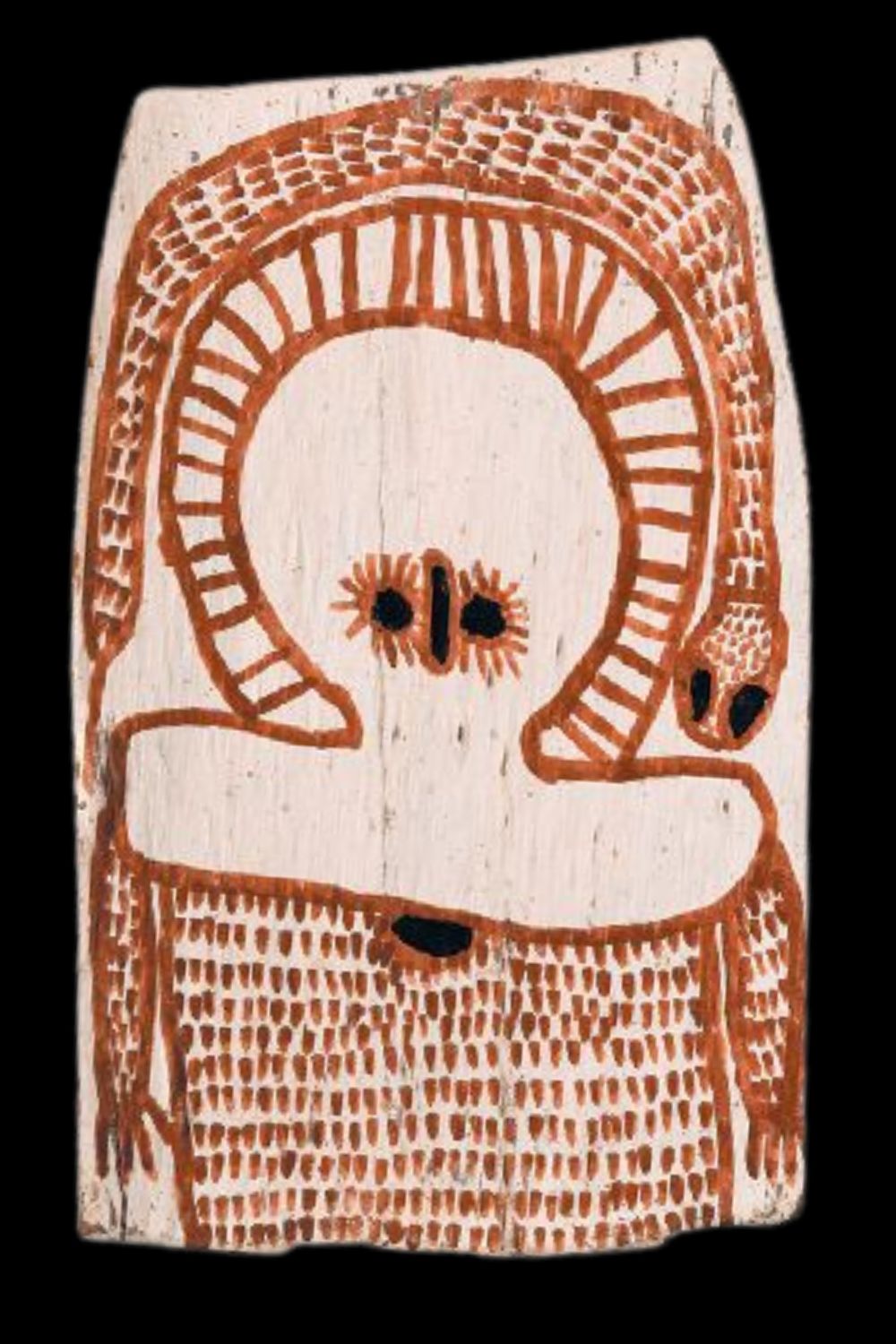

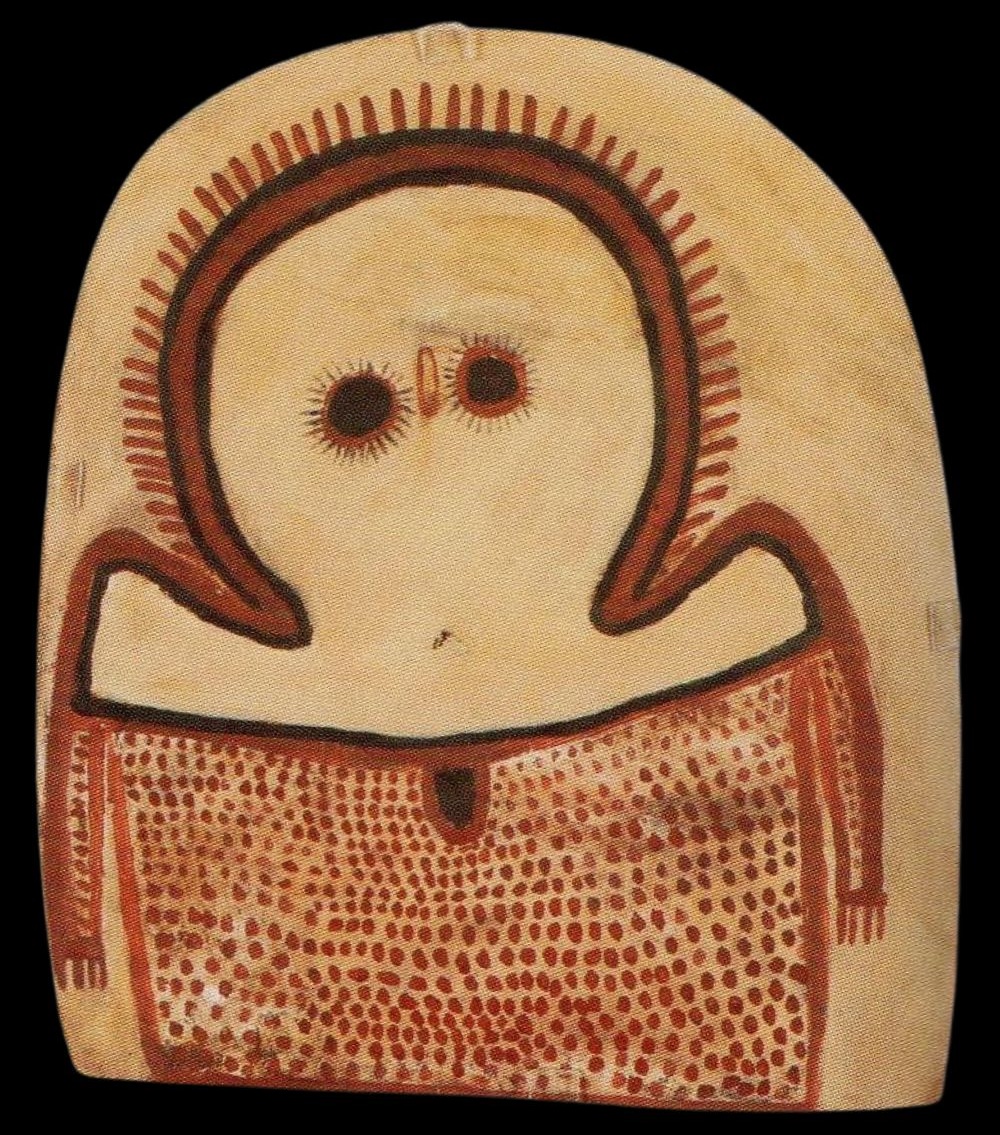

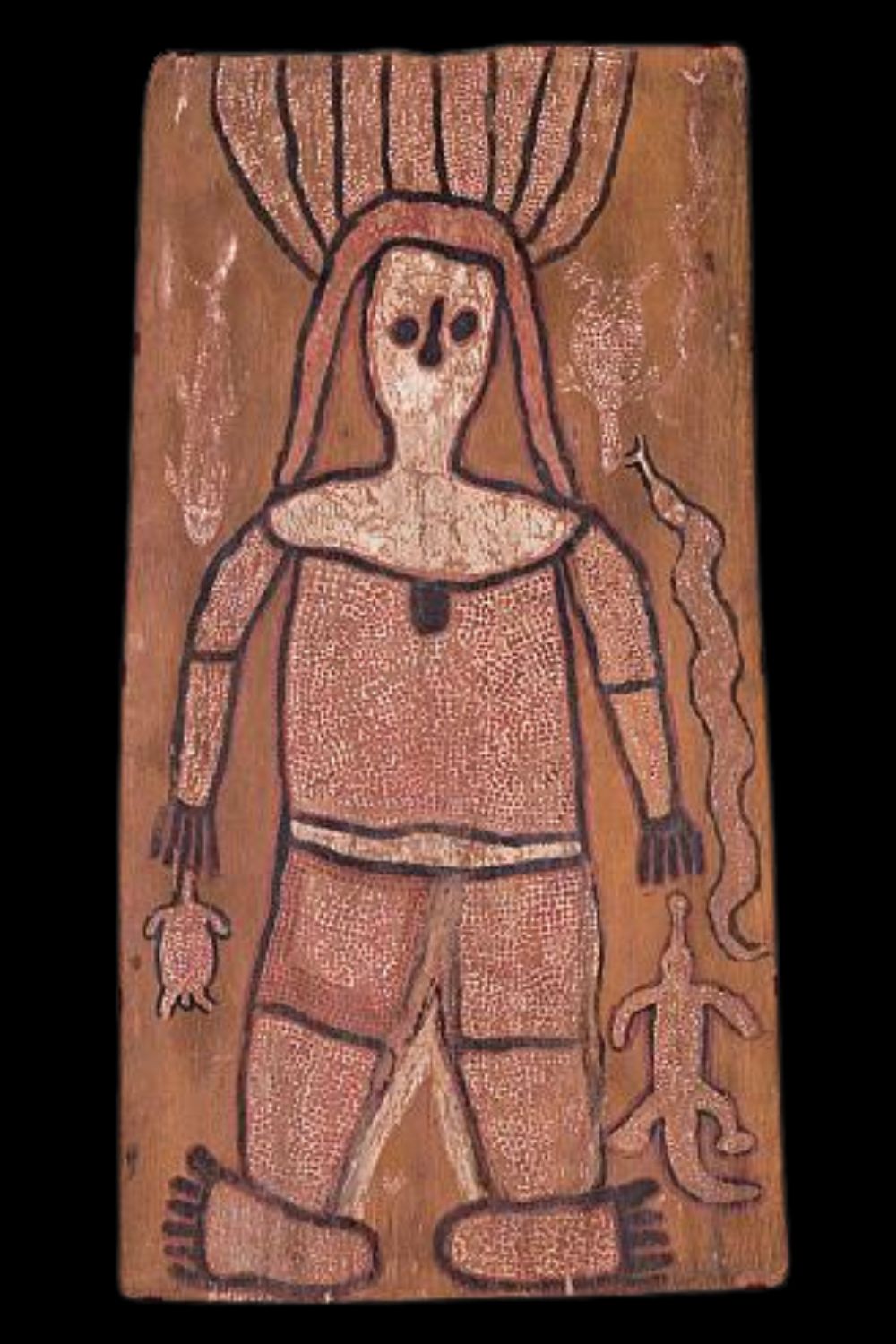

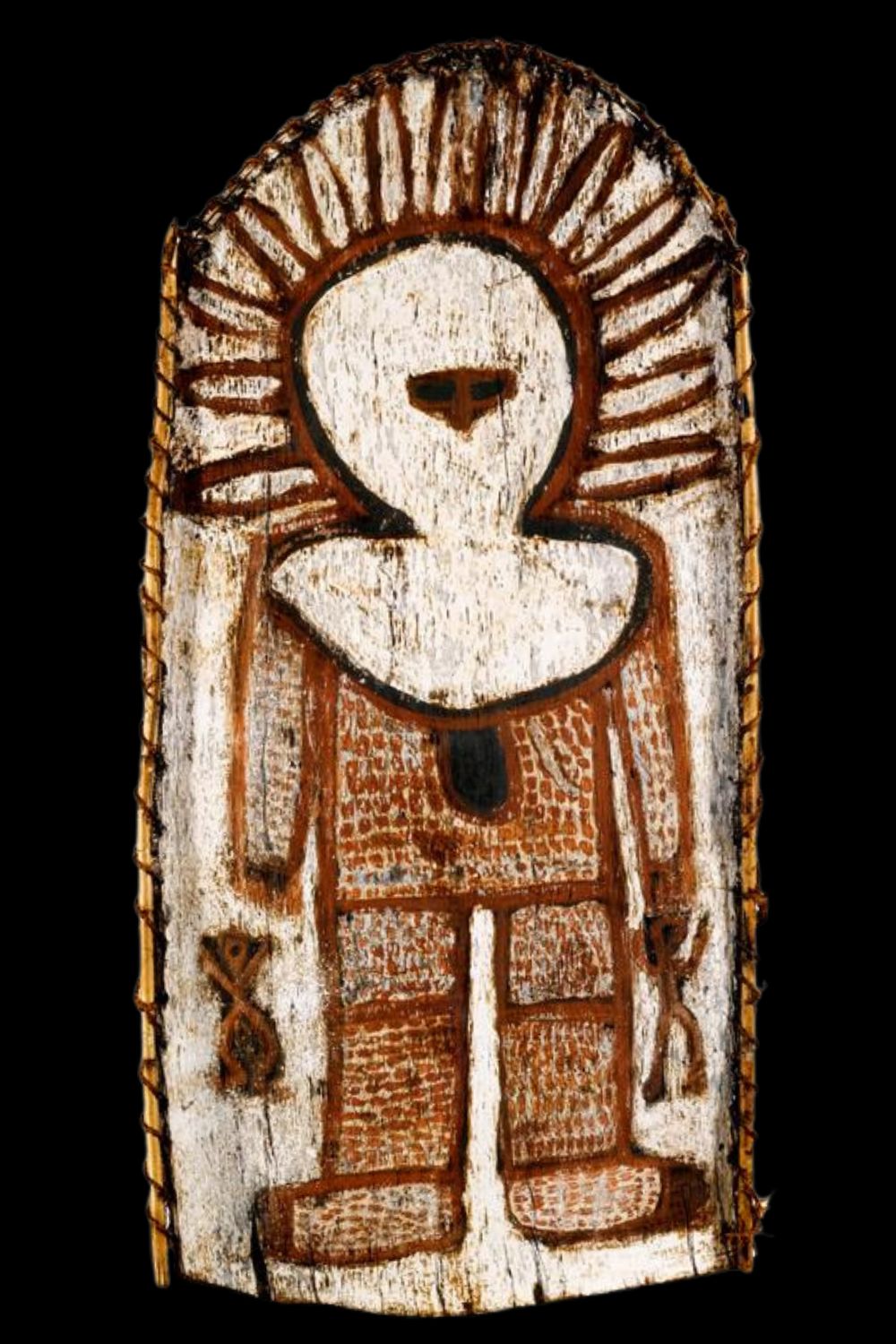

The evolution of Wanjina painting from the sandstone rock shelters of the north-west Kimberley to works on bark, board, and eventually canvas, represents one of the most compelling transformations in Australian Aboriginal art history. Painting Wandjina figures on bark is a relatively recent artistic development. German anthropologist Helmut Petri recorded a shrine-like construction adorned with Wandjina on arched bark panels in the late 1930s, suggesting early experimentation beyond the rock surface. Petri and his contemporaries—such as I. R. B. Love and A. Capell—were instrumental in collecting some of the first Wondjina bark paintings during an era of intensive anthropological fieldwork.

The earliest bark paintings from the Kimberley were created at the request of Europeans, paralleling early collection practices in Arnhem Land. These were not works of tourist commodification, but attempts—encouraged by anthropologists, missionaries, and cultural intermediaries—to record sacred iconography in a portable format. Unfortunately, early barks were often poorly prepared, with rough surfaces and fugitive pigments. Without the use of fixatives, very few pre-1970s examples have survived.

Stylistic Simplicity and the Influence of Scale

Unlike their Arnhem Land counterparts, Kimberley bark painters did not utilise cross-hatching (rarrk) or geometric body-painting conventions. Instead, the imagery remained largely figurative and straightforward—heavily influenced by the small scale of bark supports. Themes centred almost exclusively on Wanjina and serpent spirits, with limited compositional variation. Nonetheless, even within this narrower visual language, artists conveyed personal styles that reflect deep spiritual relationships to place.

Among the few recorded names from the early period are Wattie Karuwara (Woonambal), Charlie Numbulmoore(Ngarinyin), and Mickey Bungunni (Ngarinyin). As public interest in Aboriginal art intensified during the 1970s, artists such as George Jomeri (Ngarinyin), Sam Woolagoodja (Worrorra), and David Mowaljarli (Ngarinyin) emerged through the art and craft outlet at Mowanjum.

Innovation on Bark and the Mowanjum Revival

In 1974, a burst of creativity occurred at Mount Elizabeth where Ngarinyin artists produced elaborate Wandjina images on bark containers. These fragile objects, though short-lived, exemplified the period’s expressive energy. In 1970, Dr Helen Groger-Wurm assembled a landmark collection from Mowanjum for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, including large-scale Wanjina paintings on board by Karuwara, Numbulmoore, Albert Barunga, and Cocky Wutjungu.

The Role of Mary Macha and the Transition to Canvas

A pivotal figure in the development of Wandjina painting was Mary Macha, appointed in 1971 as Project Officer for the Native Trading Fund. Macha’s selective support for artists with proven talent, combined with her advocacy for the integrity of traditional materials, helped preserve the authenticity of Kimberley art. Rather than encouraging mass production, she championed a curated, artist-led approach—radically different from the community-wide workshops of Central Australia and Arnhem Land.

From 1975 onwards, artists at Kalumburu—long isolated by the Benedictine mission established there in 1907—began painting on bark, followed by canvas. Alec Mingelmanganu, Manila Kutwit, and Geoffrey Mangalmarra were among the first to embrace this transformation, often drawing direct inspiration from the nearby rock shelters.

Wondjina Street Art

Wanjina: Sacred Ancestry and Contemporary Tensions in Urban Expression

In a remarkable episode that captured both public imagination and cultural concern, Wandjina imagery—sacred ancestral beings of the Kimberley—emerged across Perth’s urban landscape in 2006. Over one hundred Wandjina-style graffiti motifs appeared on walls, trees, overpasses, and laneways, their forms ranging from respectful renditions to provocative reinterpretations. While these urban artworks echoed traditional visual markers—haloed heads, mouthless visages, and intricate infill patterns—they lacked the cultural authority underpinning true Wandjina expression. As Frederick & O’Connor illuminate, Wandjina are not merely aesthetic symbols; they are spiritual entities maintained by specific Aboriginal custodians through ceremonial repainting and deep obligations to Country, Law, and ancestral continuity. The appearance of Wandjina in unsanctioned graffiti prompted concern among Kimberley Elders, who respectfully challenged the misuse of spiritually potent imagery without proper consultation. In a powerful act of cultural diplomacy, the graffiti artist ceased their work following dialogue with community leaders. This incident underscores a core tenet in Aboriginal art: the right to depict Wanjina is not defined by artistic freedom, but by cultural legitimacy, ancestral connection, and custodial responsibility. In the world of Indigenous art, particularly in relation to Wanjina, true value lies not in novelty or urban flair—but in the depth of relational knowledge, ceremonial grounding, and inherited right.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Wandjina Artists

In the 1970’s to 1980’s Wanjina became a commercial art form and several artists surfaced as the major artists of this style. I have written artist profiles for many of these artists and these articles are previewed below.

Alec Mingelmanganu

The most famous of the early wandjina artists Alec Mingelmanganu not only Painted on Bark but also did some masterpieces on canvas.

Charlie Numbelmoore

Charlie Numbelmoore stands among the most significant Aboriginal artists of the Kimberley region and is widely regarded as a foundational figure in the visual interpretation of the Wanjina ancestral spirits. The large round haunting eyes charactirise his works

Waigin Djanghara

Waigin Djanghara was a prolific painter of Wanjina on bark. Many of these paintings however are small and need to be in great condition to spark major interest in collectors.

Lily Karedada

Lily Karedada was the single most prolific painter of Wondjina images on bark slate wood and canvass. Lily painted wandjina in a variety of styles early in her career before developing her own uniques style

Wattie Karruwara

Wattie Karruwara is one of the most important early Wanjina painters from the Kimberley region of Western Australia. As a pioneering artist in the commercialisation of Wandjina iconography, his works are now highly sought after by collectors

Mickey Bungkuni

Mickey Bungkuni was painting Wandjina of rock shelters and for anthropolgist long before commercial Wandjina painting started. His bark paintings are rare and collectable.

Ignatia Djanghara

Ignatia Djanghara like her husband was a prolific painter and they often worked in conjunction with each other and their art very difficult to distinguish from each others.

Jack Karedada

Only a dozen or so paintings of Wandjina by Jack Karedada are known to exist. His wondjina have small eyes and are often painted on arch shaped panels of bark.

Cocky Wutjungu

Very little is recorded about the life or artwork of Cocky Wutungu but he was an early wanjina painter and his art is collectable.

Manila Kutwit

Only a couple of wandjina by Manila Kutwit are known but he was an early wandjina painter working in the 1970’s.

George Jomeri

Only a few paintings of Wandjina by george Jomeri are known. The known paintings are on irregular sheets of bark and were predominantly collected by Kim Akerman

Jack Wherra

Jack Wherra is best known for his engraved Boab nuts but he did also paint Wandjina on bark and composite board.

Albert Barunga

The few known wandjina by Albert Barunga are on composite board. The eyes of his wandjina tend to be rounded rectangles.

Kimberley Artists and Artworks

Wandjina: The Ultimate FAQ on the Sacred Kimberley Rainmakers

Explore answers to the most frequently asked questions about Wandjina, the iconic ancestral spirits from the Kimberley region of Western Australia. This SEO-optimised guide offers insight into their cultural, artistic, and spiritual significance, especially in relation to Wanjina painting on rock, bark, board, and canvas.

What are Wandjina?

Wandjina are ancestral spirit beings and rainmakers deeply revered by the Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal peoples of the Kimberley. They are believed to have created the landscape, laws, and life forms during the Dreaming (Ngarranggarni) and continue to control the weather—particularly rain and storms.

They are most often represented in sacred rock art, with distinctive halo-like headdresses, large round eyes, and no mouths. Their silence is symbolic; if they had mouths, their power could unleash uncontrollable storms.

Where are Wandjina found?

Wandjina figures are primarily found in rock shelters and cave systems across the north-west Kimberley region, particularly around the Mitchell Plateau, Prince Regent River, and Lawley River areas. These sites form part of an unbroken visual tradition dating back over 4,000 years.

Contemporary Wondjina paintings are also created by Aboriginal artists on bark, board, and canvas, especially in communities such as Kalumburu and Mowanjum.

What do Wandjina paintings represent?

Wandjina paintings are not just decorative art—they are living expressions of ancestral law, country, and ceremony. Each Wandjina figure represents a specific ancestral being connected to a particular place, clan, or Dreaming track. Their iconography also includes rain clouds, lightning, and elements from the natural world.

Painting Wandjina is a sacred act usually restricted to senior lawmen or individuals with inherited rights and ceremonial knowledge.

What makes Wandjina painting different from other Aboriginal art?

Wanjina painting differs significantly from other Aboriginal art styles in several ways:

-

No rarrk (cross-hatching): Unlike Arnhem Land art, Wandjina paintings are not defined by fine geometric patterns.

-

Stylistic consistency: Wandjina often appear with circular eyes, large heads, and no mouths.

-

Spiritual restrictions: Only authorised custodians may depict Wandjina, as the images embody living ancestral spirits.

-

Medium: Initially painted on rock surfaces, Wandjina were later depicted on bark, board, and canvas from the 1930s onwards.

Why don’t Wandjina figures have mouths?

The absence of mouths on Wandjina figures is deeply symbolic. It reflects the belief that if they could speak, their words might summon endless rain and storms, disrupting the balance of life. Their silence is power, embodying the sacred restraint of ancestral energy.

When did Wandjina start appearing on bark and canvas?

Although the Wandjina tradition dates back thousands of years, the transition from rock to bark painting began in the 1930s. This shift was partly driven by anthropologists and missionaries seeking portable examples of Aboriginal art.

Wandjina painting on canvas emerged in the mid-1970s, with artists like Alec Mingelmanganu, Charlie Numbulmoore, and Lily Karedada leading a renaissance of large-scale works inspired by sacred cave imagery.

Who is allowed to paint Wandjina?

Only members of the Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal language groups with cultural and ceremonial authoritymay paint Wandjina. This knowledge is passed down through generations and must be earned through ritual responsibilities.

Painting Wandjina without permission is considered a serious cultural violation.

What materials are used in Wandjina painting?

Traditional Wandjina painting uses natural ochres—white (onmal), red (jajal), yellow (goombarroo), and black charcoal. Artists often bind pigments with goorim gum from the boorngoor tree instead of synthetic fixatives, preserving a strong connection to Country.

Modern Wanjina artworks may appear on:

-

Bark (specially prepared Eucalyptus sheets)

-

Composition board

-

Canvas

What is the difference between Wandjina and Gwion Gwion (Bradshaw) paintings?

Wandjina and Gwion Gwion are two distinct rock art traditions:

-

Wandjina: Broad, haloed, anthropomorphic figures, painted in white, red and black, dating back ~4,000 years. Still part of a living cultural practice.

-

Gwion Gwion (Bradshaw): Extremely fine and detailed figures in dynamic poses, dating over 12,000 years. The meaning of these images is now unknown, and their associated rituals have not survived.

Many Woonambal artists, such as Alec Mingelmanganu, incorporate Gwion figures into contemporary Wanjina works, linking ancient traditions with living Law.

Why are Wandjina paintings important to Aboriginal culture?

Wandjina are more than symbolic images—they are living ancestral beings who maintain the spiritual health of people and land. Painting, retouching, and caring for Wandjina sites and images is a sacred obligation, forming part of ongoing cultural and spiritual maintenance.

Their depiction in contemporary art is an act of cultural continuity and resistance—reaffirming identity, sovereignty, and ancestral connection in the face of colonisation and mission-era disruption.

Where can I view Wandjina paintings today?

You can see Wandjina art in:

-

Rock shelters (by guided cultural tours only) in the Kimberley

-

Mowanjum Aboriginal Art & Culture Centre, Derby WA

-

Kalumburu Mission community

-

Art galleries and institutions, such as the National Gallery of Australia and the Berndt Museum

-

Commercial exhibitions featuring artists like Lily Karedada, Louis Karedada, Rosie Karedada, and Donny Woolagoodja

Can Wandjina paintings be purchased?

Yes, but only from ethical sources. Authentic Wandjina artworks created by recognised Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Wunambal artists are available for purchase through:

-

Reputable Aboriginal-owned art centres (e.g., Mowanjum, Waringarri)

-

Specialist galleries focused on provenanced Indigenous art

-

Exhibitions curated by institutions like the Art Gallery of Western Australia

Buyers should always request information about the artist, language group, and permission to depict Wandjina. Avoid unverified or unauthorised reproductions.

Why was the 1987 Mount Barnett Wandjina restoration controversial?

In 1987, a well-intentioned but culturally insensitive project funded by the Commonwealth Employment Project authorised non-custodial Aboriginal youth from Derby to “restore” Wandjina sites on Mount Barnett Station. Without consulting traditional owners from Kupungarri, eight sacred sites were overpainted, resulting in irreparable cultural damage.

This incident highlighted the critical need for community control and cultural permission in any conservation of sacred sites.

What does the future hold for Wandjina painting?

Wandjina painting remains one of the most potent visual expressions of Aboriginal spirituality and cultural authority. With the ongoing stewardship of traditional custodians and the artistic leadership of new generations, Wondjina painting continues to evolve—balancing respect for ancient Law with contemporary artistic expression.

The future lies in cultural continuity, ethical support for Aboriginal art centres, and the recognition of Wanjina painting as a world-significant spiritual tradition.