Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek (c.1926–2009): Master of Western Arnhem Land

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek stands among the great masters of Western Arnhem Land Oenpelli painting, renowned for his exquisite command of parallel line hatching—a stylistic hallmark that sets his work apart from the broader rarrk tradition. His bark paintings are immediately recognisable: rendered on rectangular sheets of eucalyptus bark, often with a monochrome background of rich red or black charcoal, they exhibit a rare intensity and refinement of line.

As a dedicated specialist in the works of Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek AO, I actively collect and place his paintings with discerning institutions and private collections. Should you possess an original work by this esteemed Kunwinjku master please feel free to send me an image.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, including those influenced by Yirrkala cross-hatching, Nadjamerrek favoured the single-directional hatching practiced by earlier masters such as Dick Murramurra. His technique relies on the meticulous layering of fine, closely spaced lines. He often reveals the internal anatomy—spines, organs, and skeletal structures—affirming the spiritual reality of each subject in accordance with Kunwinjku ceremonial tradition.

A senior cultural custodian and initiated elder, Lofty Nadjamerrek was not educated in European institutions but instead received the full ceremonial instruction of his people. He held deep knowledge of ancestral stories and songlines, and was widely respected for his role as a traditional leader and teacher across the Stone Country of Western Arnhem Land.

Nadjamerrek began painting commercially in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) in 1969, producing barks for the growing art market. His subjects frequently include the native animals of his homeland: kangaroos, echidnas, crocodiles, turtles, birds, and Barramundi and catfish, all imbued with a sinuous, elegant movement that reflects the dynamic energy of the landscape and the spirit beings who inhabit it.

Namarrkon By Lofty Nadjamerrek

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek: The Last Master of Classical Oenpelli Painting

Few Aboriginal artists have achieved the artistic output, longevity, and national recognition of Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek (also known as Nabadayal, Bardayal, or Nabardayal). A towering figure in the development of Western Arnhem Land bark painting, Nadjamerrek was remarkably prolific—second only to Yirawala in the sheer number of recorded works. His long and dedicated passion, spanning decades of continuous production, has earned him a place of distinction in museums, galleries, and private collections worldwide.

Nadjamerrek’s compositions, possess a measured clarity and formal elegance that appeals to both traditional and European sensibilities. While early Arnhem Land painters like Djambalula or Diidja. expressed a raw, elemental force in their works, Lofty’s aesthetic is more refined—calm, sinuous, and contemplative, yet deeply grounded in ancestral Lore.

He is notably the only Aboriginal bark painter to have been awarded the Order of Australia, the country’s highest civilian honour—a recognition not only of his artistic brilliance but of his role as a cultural leader and custodian. His death in 2009 marked the symbolic end of a foundational generation of Oenpelli artists, who bridged pre-contact rock art traditions with modern bark painting for the public sphere.

Despite failing eyesight in his final years, a result of Trachoma, Nadjamerrek continued to paint slowly and meticulously until the end of his life. He produced powerful works on paper and card, although many collectors continue to prize his earlier bark paintings.

A father of eight, Nadjamerrek’s artistic legacy is singular. Though none of his children followed him into painting, his works endure as a vital link to Arnhem Land’s rock painting traditions, some of which he himself contributed to. His early rock art depictions of kangaroos, emus, goats, and even a horse and rider, still grace the walls of shelters at Kodwalehwaleh, speaking to his unbroken connection to Country and spirit.

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek remains one of the most collected, respected, and studied Aboriginal artists in the history of Australian art—his legacy a testament to the power of Indigenous knowledge, innovation, and cultural resilience expressed through paint on bark.

References and Extra Reading

Keepers of the secrets: Aboriginal Art from Arnhemland

Crossing Country: The Alchemy of Western Arnhemland Art

Lofty Nadjamerrek Artworks meanings explained

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek and the Rainbow Serpent: Mythic Power in Bark

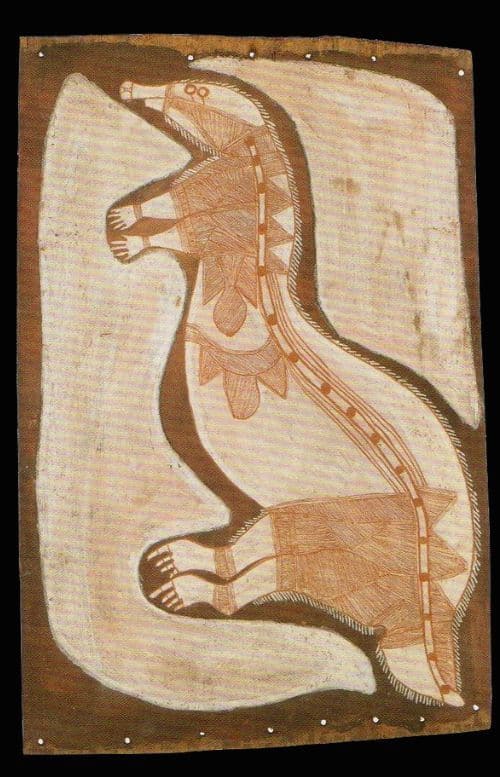

Among the most arresting subjects in the oeuvre of Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek are his depictions of the Rainbow Serpent, particularly Ngalyod and Namarrkon, the Lightning Spirit. Through his distinctive parallel line hatching and finely modulated figuration, Lofty imbued these mythic beings with both ceremonial gravity and dynamic presence. His bark paintings do more than depict—they evoke transformation, embodying the sacred forces that animate the landscape and law of Western Arnhem Land.

In the cosmology of the Kunwinjku people, there are three known Rainbow Serpents. The most ancient and powerful is Jingana, the Mother Serpent, who dwells in subterranean chambers and lily-covered billabongs, guarding the primordial balance of nature. Dissatisfied with the early hybrid creatures—part human, part animal—Jingana once swallowed the world and remade it. From her belly, she birthed two sacred offspring: her son Ngalyod, with a crocodilian head and sinuous serpent body; and her daughter Ngalgunburijaimi, whose form combined serpent, crocodile, and fish. Both inherited bony chests and ceremonial spurs, symbols of ancestral potency and spiritual danger.

It is Ngalgunburijaimi, the lesser-known female Rainbow Serpent, who features in this particular bark painting by Nadjamerrek. Rarely depicted in Arnhem Land iconography, her inclusion here signals not only Lofty’s deep ceremonial knowledge but his willingness to render esoteric beings with precision and reverence. Her appearance, like that of her brother and mother, is both beautiful and fearsome—a reminder of the serpents’ dual nature as creators and destroyers.

During the wet season, these serpents ascend into the stormclouds, their tongues stirring thunder, lightning, and monsoonal rains. But if offended—if laws are broken, if sacred waterlily habitats are disturbed—they may unleash unseasonal storms, destroy vital ecosystems, or swallow transgressors whole. Aboriginal custodians of the land, including Nadjamerrek, honour these serpents through ritual and imagery, maintaining harmony between people and ancestral powers.

By capturing these sacred narratives on bark, Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek ensured that ancestral law (mardayin) was not only remembered but also visually preserved for future generations. His Rainbow Serpent paintings stand among the most spiritually charged and compositionally refined works in the canon of Australian Aboriginal art.

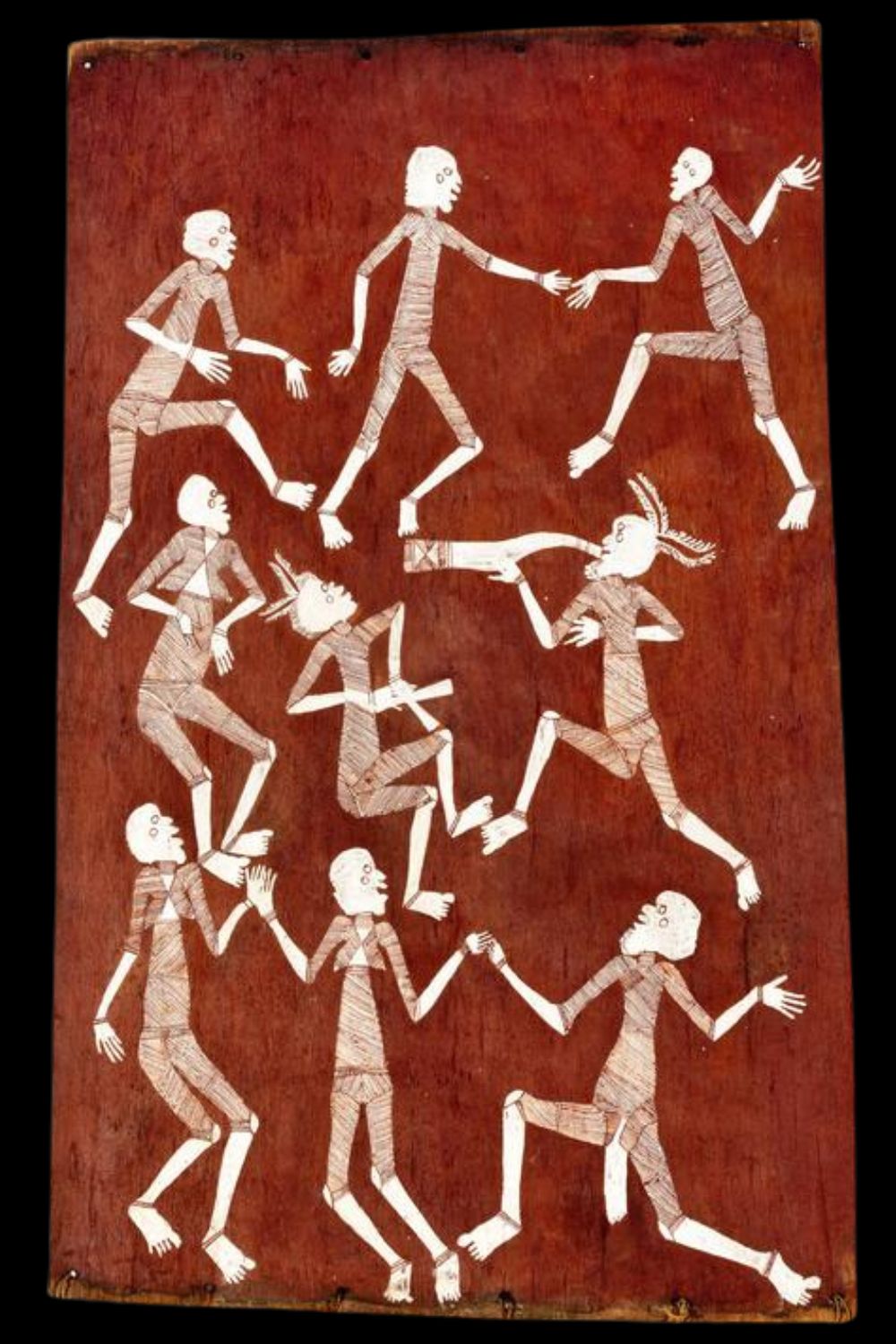

Mimih Hunter Dreaming: Ancestral Encounter in the Stone Country

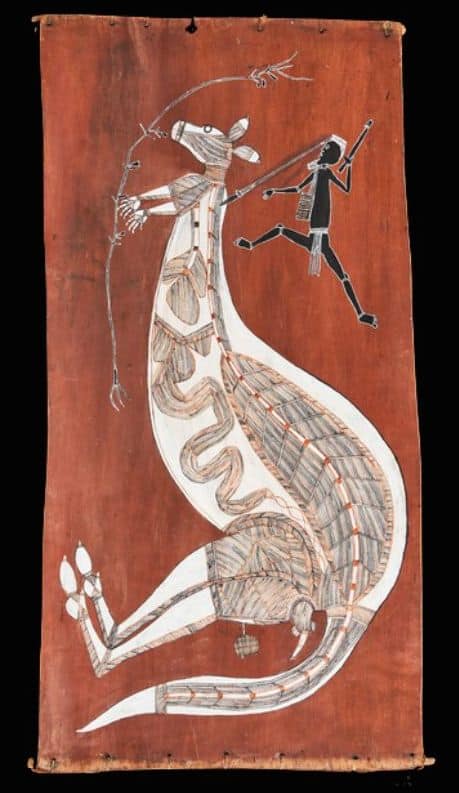

In this exceptional bark painting, Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek renders the dramatic ancestral tale of Djala, a hunter, and his fateful encounter with the enigmatic Mimih spirits—slender, elusive beings said to dwell deep within the rocky escarpments of Western Arnhem Land. This narrative, part of the Mimih Dreaming, carries powerful lessons about respect, reciprocity, and the hidden dangers of the spiritual realm.

According to Kunwinjku oral tradition, Djala and his heavily pregnant wife lived in close proximity to a towering sandstone ridge known to be a Mimih domain. One day, while tracking a large kangaroo into the setting sun, Djala witnessed a Mimih spirit—Kaman—dispatch the animal with supernatural precision. Rather than challenge the being, Djala offered respectful praise, recognising the Mimih’s skill with the spear.

In response, Kaman invited Djala to share in the kangaroo meat. Aware of the dangerous magic associated with the Mimih—especially the power they could wield through possession of human hair or bodily fluids—Djala hesitated. But curiosity and hunger led him to follow.

Kaman blew upon a sheer rock face, which split open to reveal a hidden passage. Beyond lay a lush, secret glade where kangaroos grazed unafraid—a place untouched by the ordinary laws of nature. At the far end stood a cave lit by ancestral song and firelight, where Mimih women danced in welcome.

Realizing if he ate the magical food he would never leave the camp and see his wife again Djala tried to leave. He asked politely if he could take a section of the kangaroo and walk back to his camp. Kaman put him off and insisted he stays the night. With Mimih women singing he fell to sleep into a deep sleep in the cave. He awoke feeling the fingers of Kaman’s wives stroking him all over. He faked sleep knowing that if they knew he was awake he would be seduced and become one of them.

In the early morning by the light of the stars, Djala crept out of the Mimih cave and glade and returned home to his wife.

In Nadjamerrek’s masterful composition, the Mimih spearing the kangaroo is captured with measured grace. His use of parallel line hatching lends ethereal tension to the scene, while the delicate rendering of Mimih forms—tall, wispy, otherworldly—evokes their fragility and power. The scene is not merely a myth but a cultural instruction, a reminder of the thin veil between the physical and ancestral realms.

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek’s “Mimih Hunter Dreaming” is an insight into the esoteric ceremonial knowledge of the Stone Country and the sacred responsibility of those who carry its stories. As both image and archive, it reflects Lofty’s lifelong commitment to ensuring the survival of Arnhem Land’s spiritual legacy, one bark at a time.

Ngarrbek, the Echidna: Ancestral Conflict and Ceremonial Power

In the rich ceremonial life of the Kuninjku people of Western Arnhem Land, few creatures hold greater symbolic significance than Ngarrbek, the Echidna. Frequently depicted in the bark paintings of artists such as Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek, Yirawala and Marralwanga Ngarrbek appears not merely as an animal, but as a key ancestral actor within the sacred Yabbadurruwa ceremony—one of two major ceremonial cycles practiced by the Kuninjku, alongside Kunabibbi.

These paired ceremonies are not merely performative; they are believed essential to the spiritual maintenance of the land, marking the seasonal renewal brought about by the onset of the wet season. Each ceremony carries reciprocal roles for different social groups and reaffirms the principles of Ancestral creation and interconnection between beings, people, and place.

Central to this spiritual drama is the creation story of the battle between Ngarrbek and the cannibal spirit being Ngalmangiyi. The myth recounts how Ngalmangiyi consumed a child of the Kodjok subsection, provoking Ngarrbek to seek vengeance. In the ensuing battle, Ngalmangiyi hurled many spears at Ngarrbek—spears that did not kill, but instead transformed into the echidna’s characteristic spines. Ngarrbek survived the attack, and his transformation stands as a symbol of resilience, transformation, and sacred memory.

In the hands of master painters like Nadjamerrek, the form of Ngarrbek is rendered with subtlety and strength, its quills suggested by sharp, deliberate strokes that reference both spear and spine. These visual metaphors echo through ceremonial performance and song, embedding ancestral law into every gesture of paint.

All images featured in this article are presented strictly for educational and informational purposes.

This website may include copyrighted material for which specific authorization has not been obtained from the copyright owner.

All such images are presumed to be the intellectual property of the respective artist or their estate, and are used in accordance with principles of fair dealing or fair use under applicable copyright law.

Oenpelli Art and Artist Articles

Frequently asked questions about Lofty Nadjamerrek

Who was Lofty Nadjamerrek?

Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek AO (c.1926–2009) was one of the most celebrated Aboriginal artists of Arnhem Land and the last practicing rock painter to transition to bark painting in the Western art market. A senior figure of the Mok clan from the Kubalwarnamyo region in the Stone Country of Western Arnhem Land, his works are deeply rooted in Ancestral Law (Djang) and reflect a direct lineage to rock art traditions dating back tens of thousands of years.

What is Lofty Nadjamerrek known for?

Lofty Nadjamerrek is best known for his refined bark paintings and rock art murals that depict ancestral beings such as Namarrkon (the Lightning Spirit), Yawkyawk water spirits, kangaroos, wallabies, and spirit men, rendered with an unparalleled command of rarrk (cross-hatching) and anatomical stylisation. His figures often feature a distinctive three-quarter profile with frontal feet, a hallmark of his hand and a direct reference to his rock art heritage.

Is Lofty Nadjamerrek’s art valuable or collectible?

Absolutely. Nadjamerrek’s works are highly sought after by museums, collectors, and institutions worldwide. His bark paintings, prints, and rare rock art photographs are represented in major collections including the National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Berndt Museum, and the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection in the U.S. As a recipient of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2004 and subject of multiple museum retrospectives, his legacy is assured—and his works continue to appreciate in both cultural and market value.

What distinguishes Lofty Nadjamerrek’s painting style?

Nadjamerrek’s artistry is characterised by:

-

Precise, hairline rarrk cross-hatching, often in black, white, and red ochre

-

Spiritual anatomy, where internal organs are depicted as part of the ancestral form

-

Fine profile figuration, echoing the formal conventions of prehistoric rock art

-

Minimalist earth tones, reflecting his deep connection to stone escarpment country

What is the cultural significance of his work?

Nadjamerrek’s paintings are not merely visual artworks—they are codified expressions of Aboriginal Law, territory, and cosmology. As a senior knowledge-holder, he used painting to pass on restricted ceremonial stories, encode geographic knowledge, and assert his custodianship over the Karnbambarnja plateau and surrounding sites. His work serves as an unbroken link between ancient rock art and contemporary Indigenous art practice.

Where can I buy a Lofty Nadjamerrek painting?

His works appear at auction through Sotheby’s, Bonhams, and Deutscher and Hackett, and can also be sourced through reputable Indigenous art dealers and galleries adhering to the Indigenous Art Code. Due to their rarity, strong provenance and early works from the 1960s–1980s can command premium prices.

Did he sign his works?

Many of Nadjamerrek’s works are unsigned in the Western sense but are instantly recognisable to experts. Later in his career, he sometimes signed with “Lofty” or “Bardayal” on the reverse, particularly for commissioned works. His stylistic fingerprint—the unique figural structure and signature cross-hatching—is widely acknowledged in curatorial circles.

How did Nadjamerrek influence other Aboriginal artists?

Lofty Nadjamerrek was not only an artist but a mentor and community leader. In 2001, he co-founded the Warddeken Land Management project at Kubalwarnamyo, where he trained younger rangers and artists in both ecological and cultural practices. His influence extends through the work of his descendants and disciples, including artists such as Gabriel Maralngurra, Jimmy Njiminjuma, and Wesley Nganjmirra, who continue to carry forward his visual language.

What is the connection between his bark paintings and rock art?

Lofty Nadjamerrek is often described as “the last great rock painter” because he was one of the few artists who actively painted on rock surfaces well into the late 20th century before transitioning to bark. His bark paintings retain the formal discipline, spiritual charge, and anatomical stylisation of traditional rock art, making his oeuvre one of the most important bridges between ancient and modern Aboriginal visual traditions.

Why is his work important to Australian art history?

Nadjamerrek’s career spans the entire history of modern Aboriginal art—from early mission-era bark paintings through to the international acclaim of the contemporary Indigenous art movement. He is recognised as a national cultural icon, a custodian of endangered knowledge systems, and a master technician whose work embodies both ancient continuity and modern resilience.