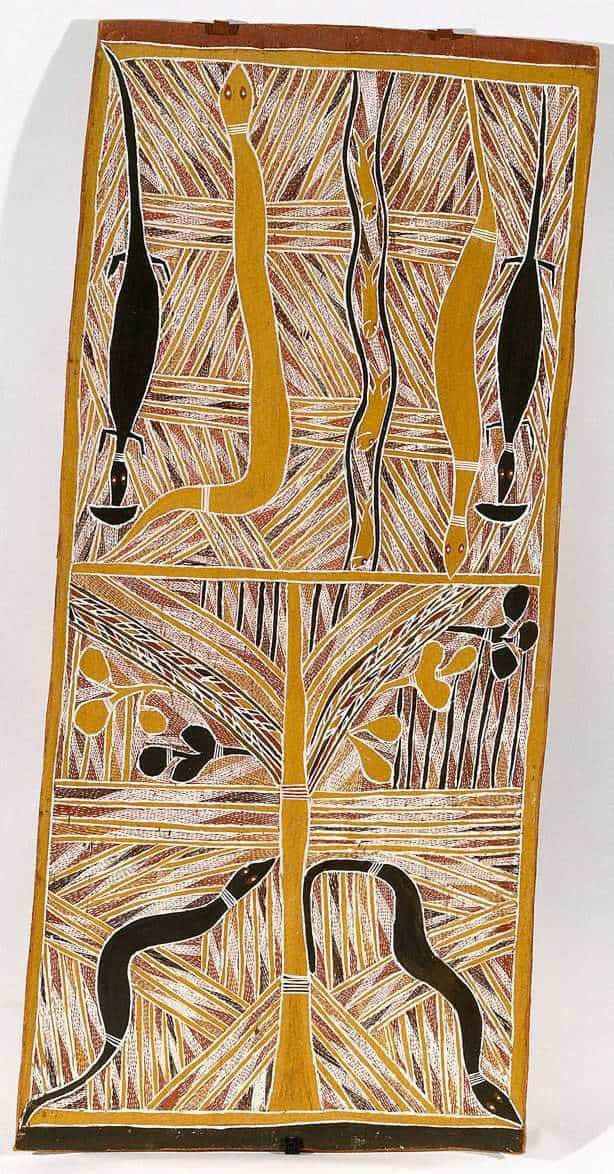

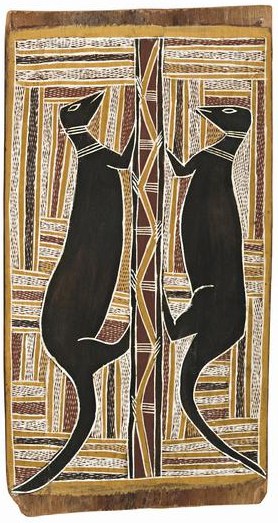

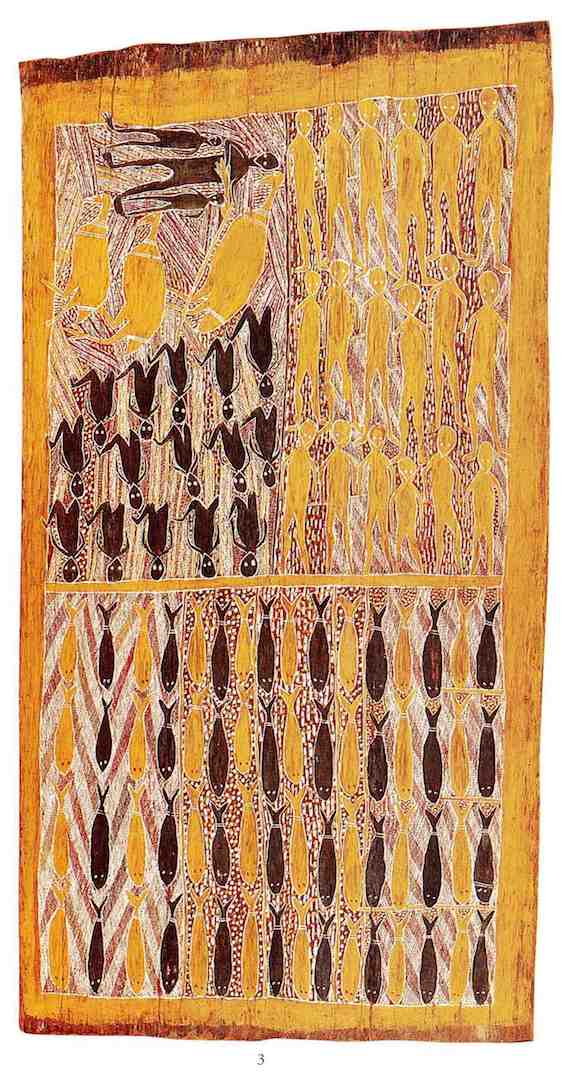

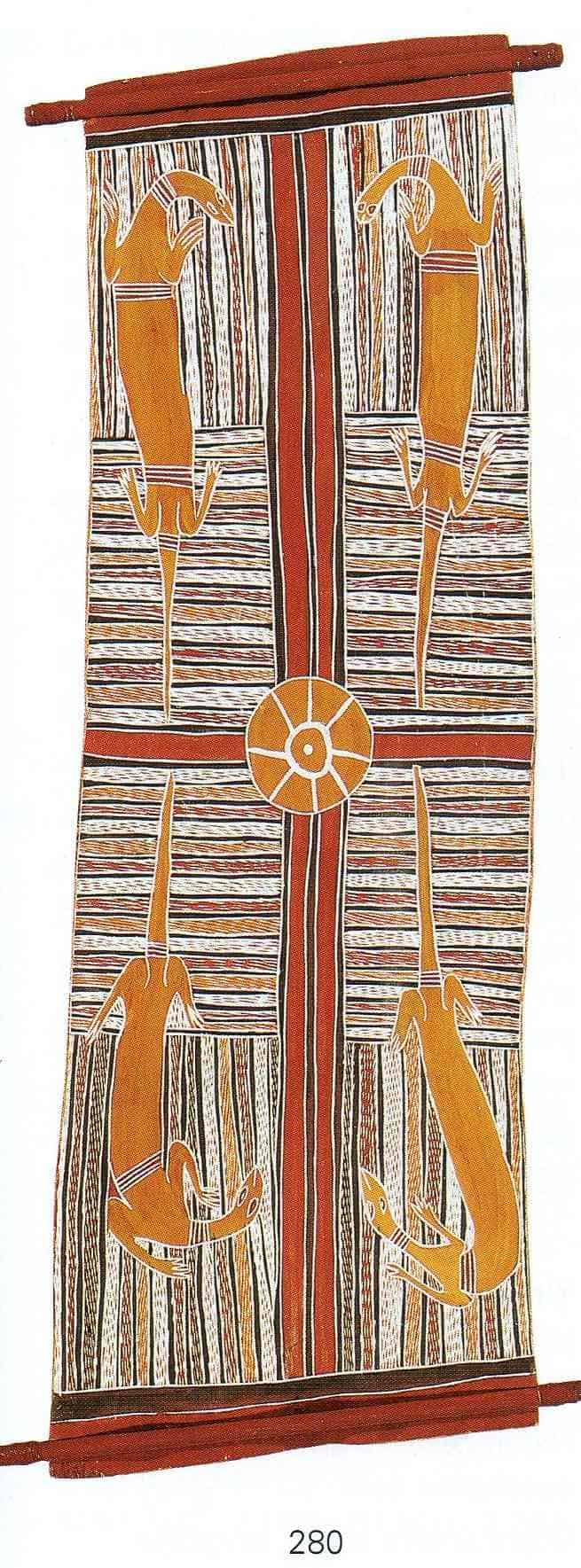

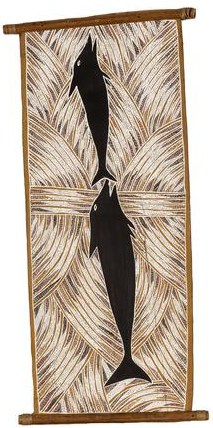

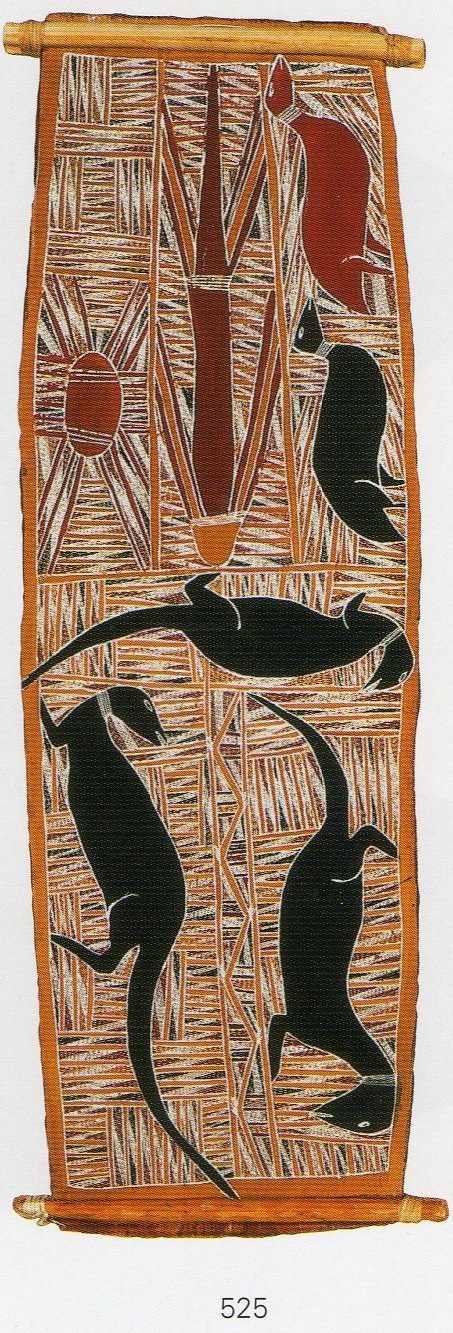

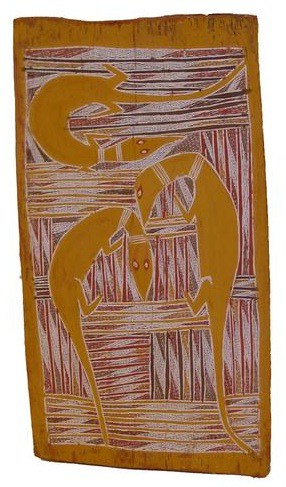

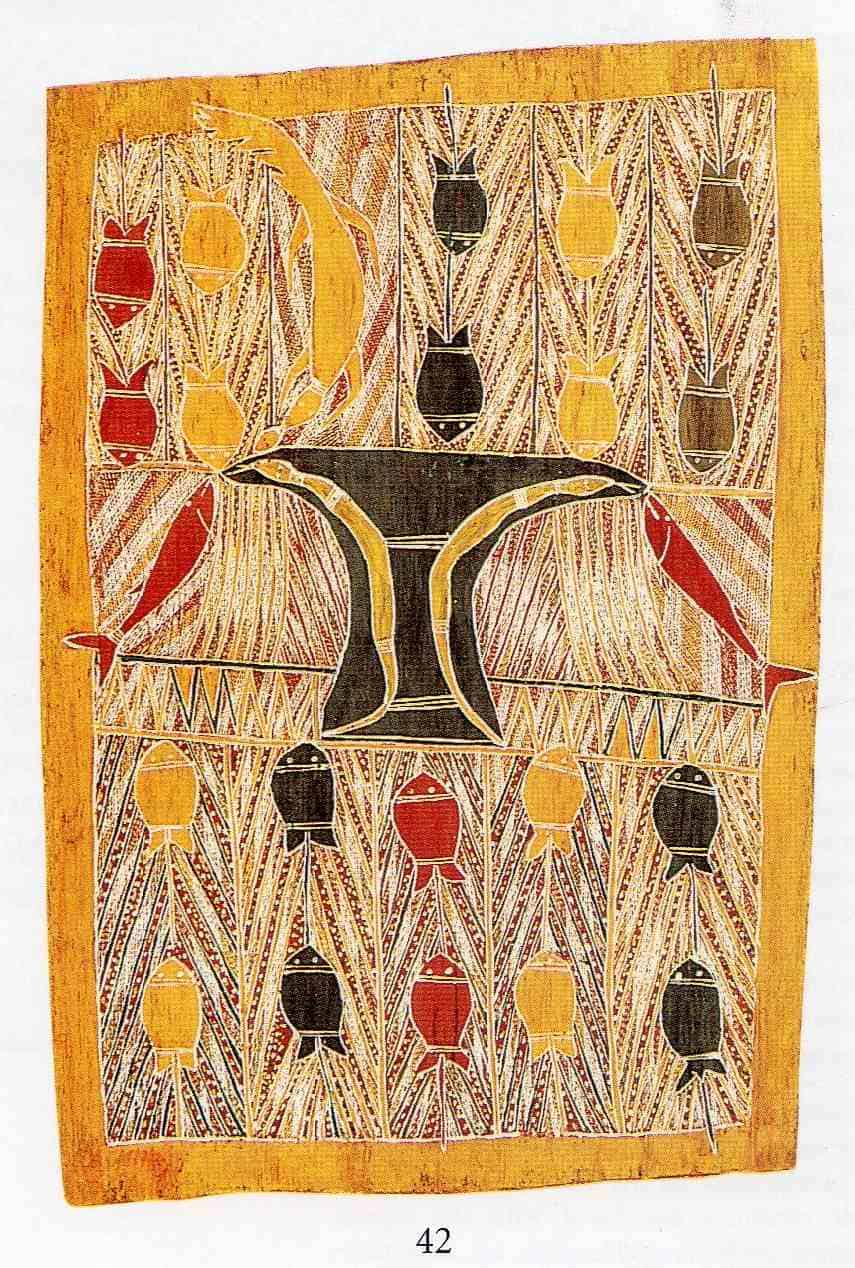

Wanjug Marika Yirrkala Bark Painter

The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their aboriginal bark painting is by Wandjuk Marika. It compares examples of his work.

If you have a

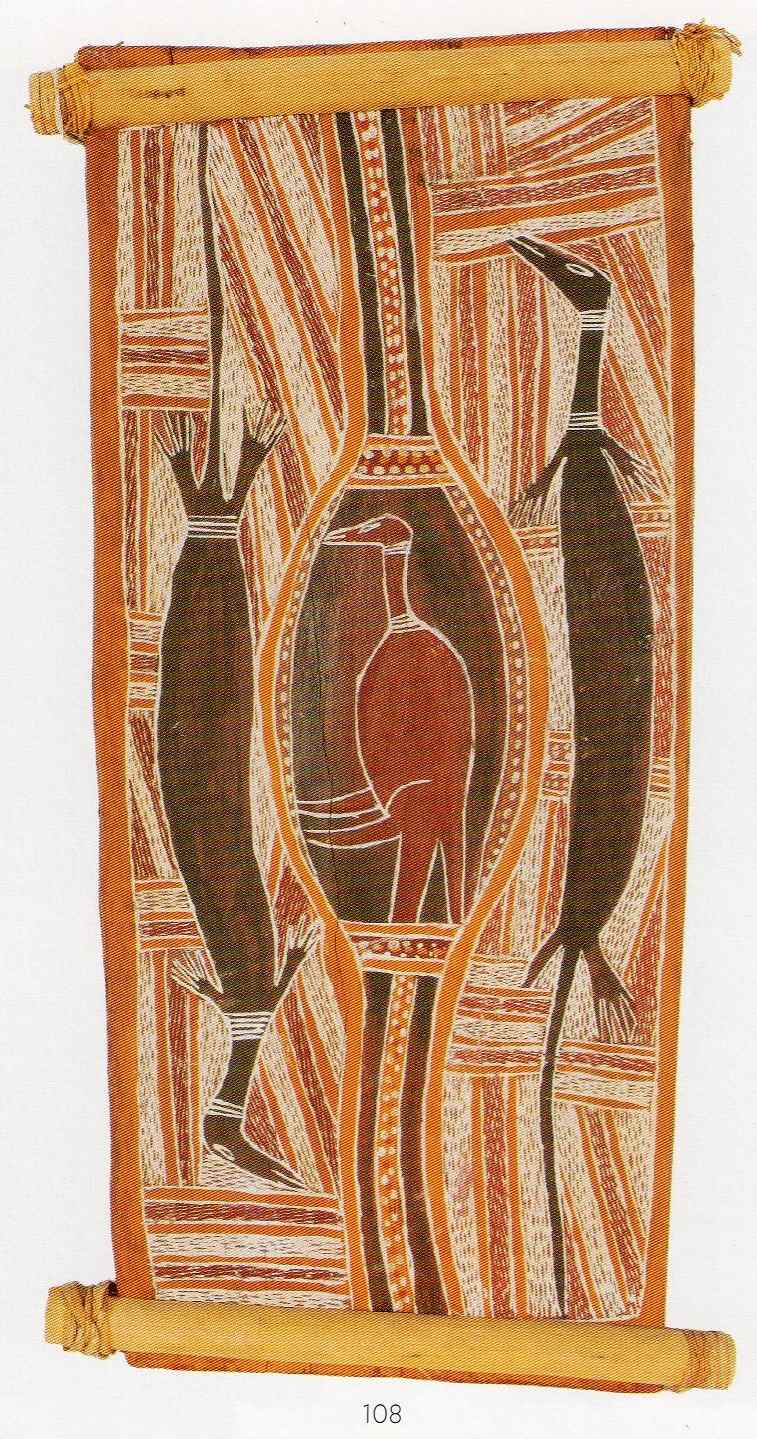

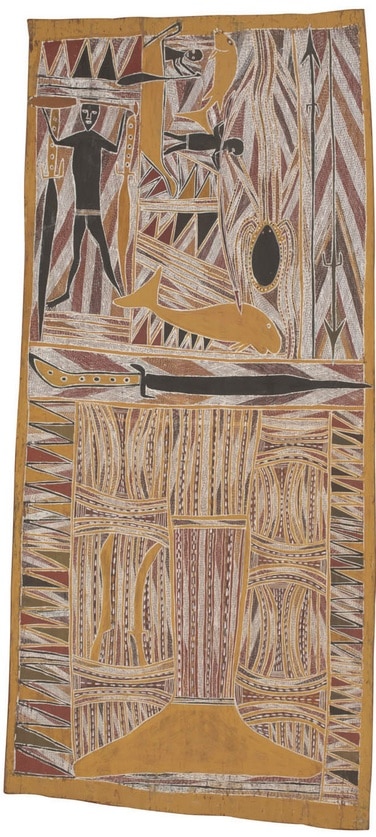

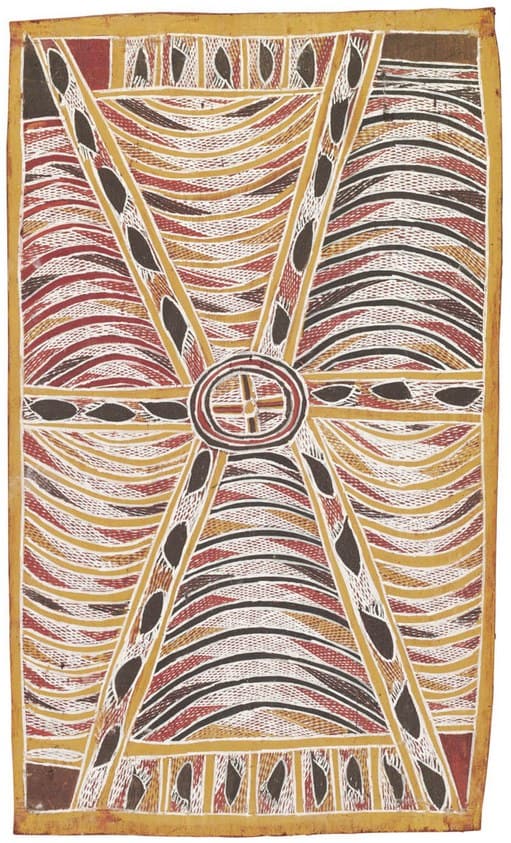

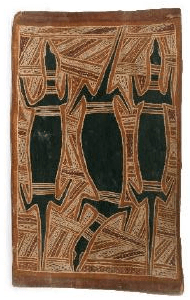

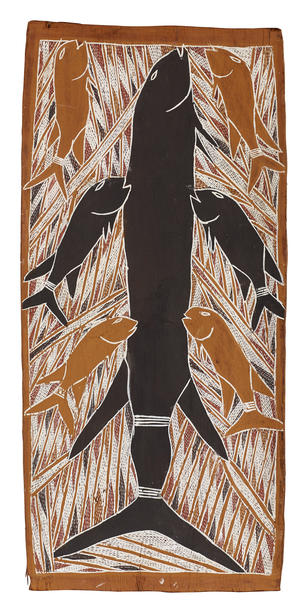

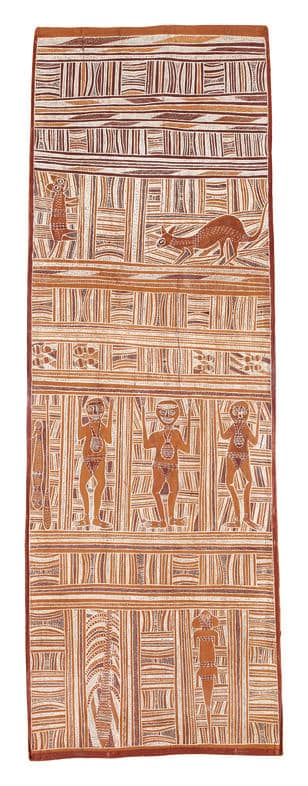

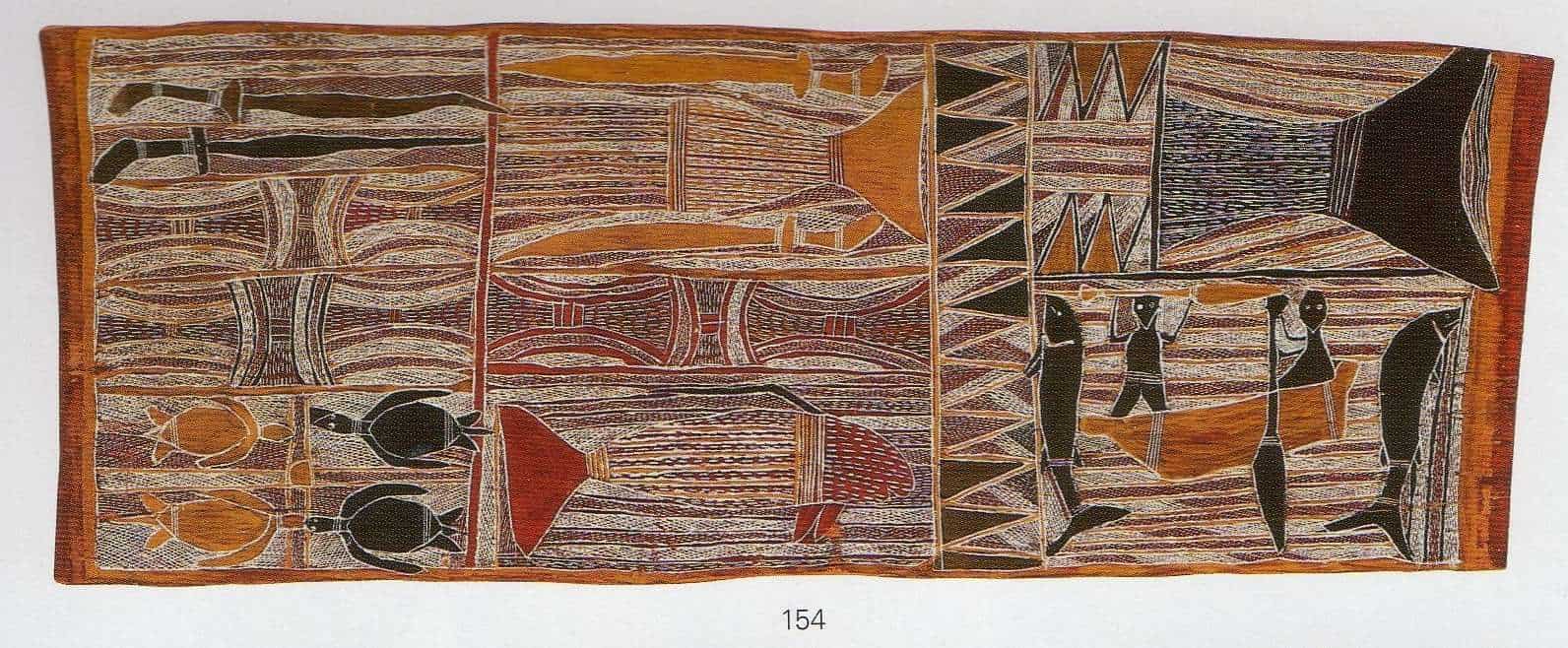

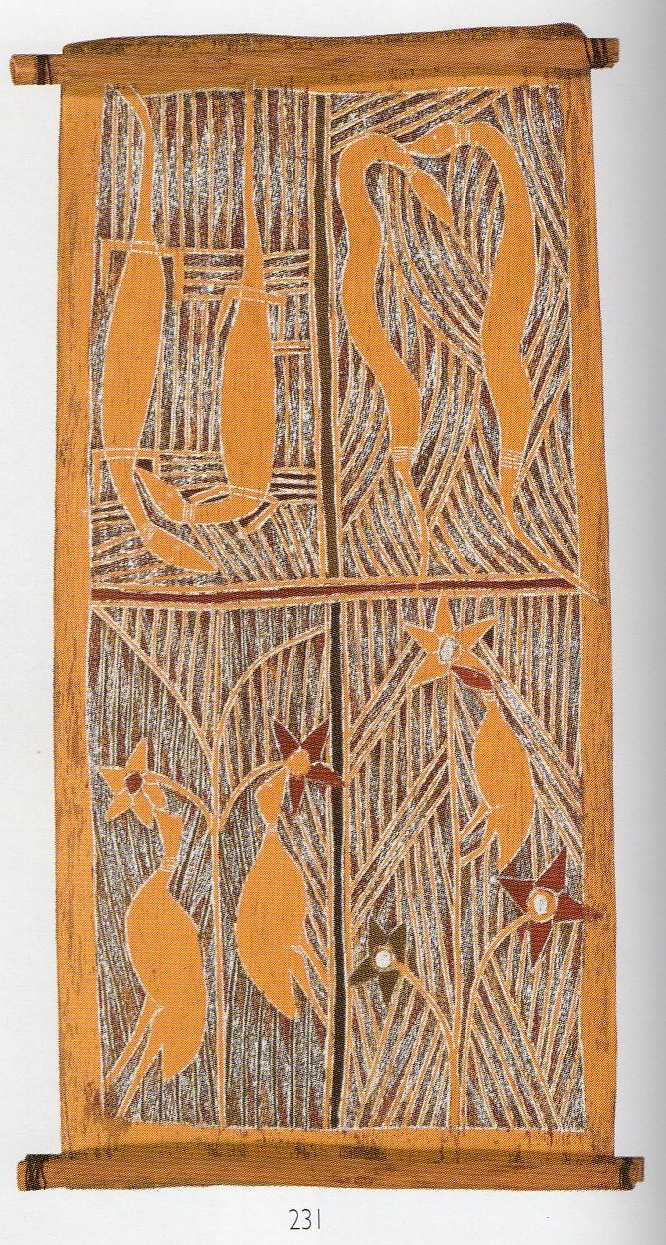

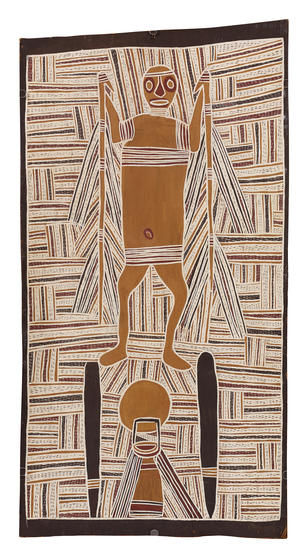

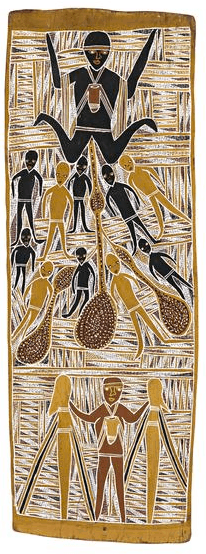

Style

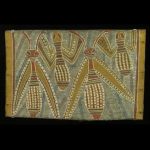

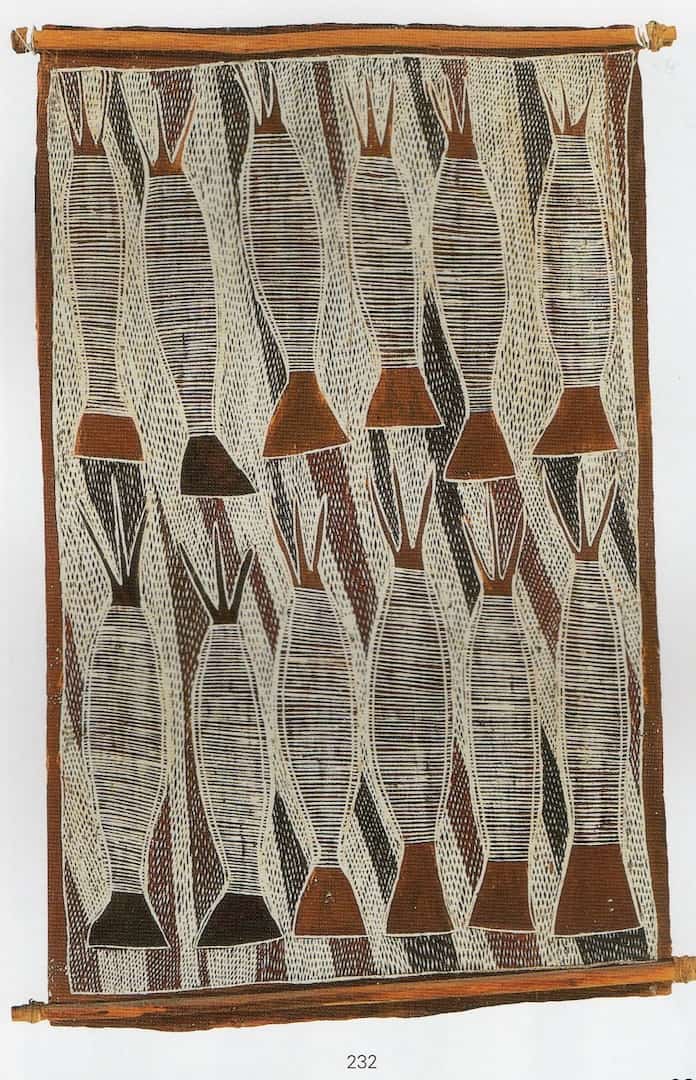

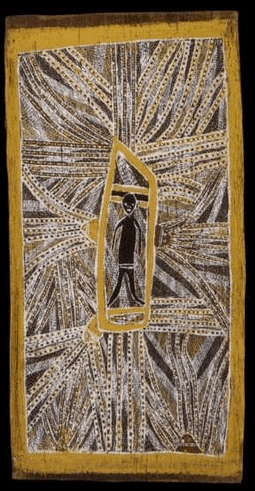

Wanjug Marika painted in an eastern Arnhem land style covering the entire bark but bordering it on all four sides. His paintings tend to have animals or figures predominantly in a single color surrounded by rarrk. Due to his high clan status, he could use sacred yellow and does so prolifically in many of his works.

Many of his works in separate panels but others are a single panel. His totemic animals include snakes lizards emu turtles and catfish.

He also did some later barks that appear more commercial.

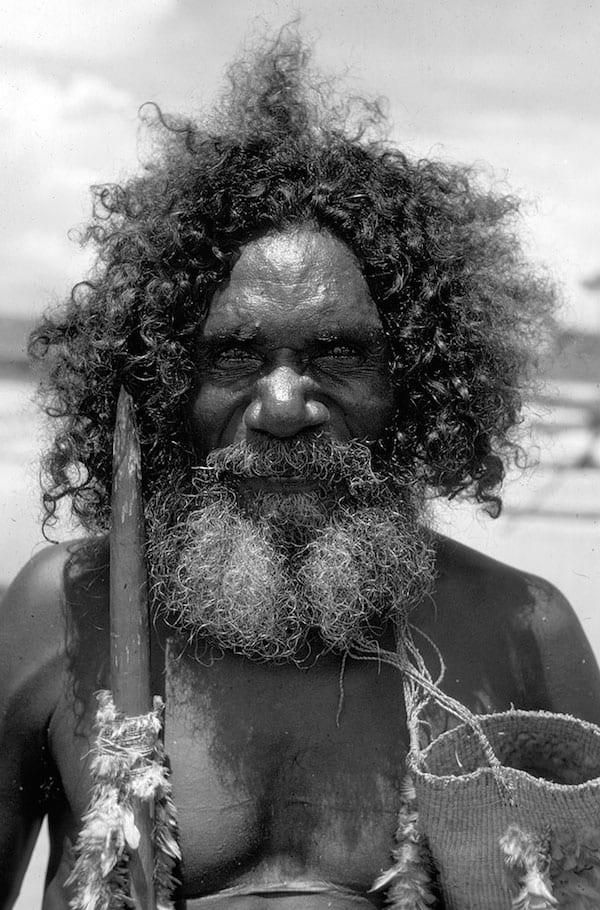

Biography

During childhood, Wanjug Marika traveled by foot throughout north-east Arnhem Land. He also traveled by canoe around the coast from Melville to Caledon bays. When his father Mawalan Marika died he became a clan leader and inherited extensive rights to land.

He went to school at the Mission station at Yirrkala and went on to become a teacher’s assistant in the mission school. He translating the Bible into his own language Gumatj. As a young man, he interpreted for his father and others for anthropologists visitors, and researchers.

In 1963 Wanjug Marika was a catalyst for the protests of several clans against the decision to grant mining leases on the Gove Peninsula. In August 1963 he helped to send the first of several bark petitions to the Commonwealth government. These barks were a sign of traditional ownership rights.

Marika learned to paint barks by watching his father. They undertook collaborative paintings of the great Rirratjingu clan themes. Galleries and museums acquired these barks in the 1950s and 1960s. He soon became a major artist like his father. Marika was a member of the Aboriginal arts advisory committee of the Australian Council for the Arts (1970-73). He was also heavily involved in the Aboriginal Arts Board, which he chaired in 1975-80.

Later Life

He assisted Birrikitja and Yunupingu with painting the Yirritja church panels. The church panels are now in the Buku-Larrnggay Museum.

In 1973 he was angry at finding his interpretations of spiritual themes reproduced on souvenir towels. This led him to lobby for the creation of the Aboriginal Artists Agency in 1973 to protect Indigenous intellectual property.

He worked closely with ethnographic and documentary film-maker. He also had musical talent and was a powerful didgeridoo player.

In 1979 he got an OBE. He died on 15 June 1987 and buried with full Indigenous rites.

His works were recently exhibited at the Old Masters Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia.

Wanjug is sometimes spelled Wondjuk or Wondjug. He is also known by the name Djuakan.

Wanjug Marika on Didgeridoo

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Yirrkala Artworks and Articles

Wanjug Marika Bark Painting Images

The following images are not a complete list of his bark painting. They do however give a very good idea of the style and variety of the artist