Narritjin Maymura Yirrkala Bark Painter

Narritjin

The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their bark painting is by Narritjin

If you have a Narritjin Maymuru bark painting to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your Narritjin Maymura painting is worth please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

Style

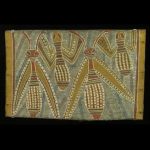

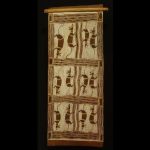

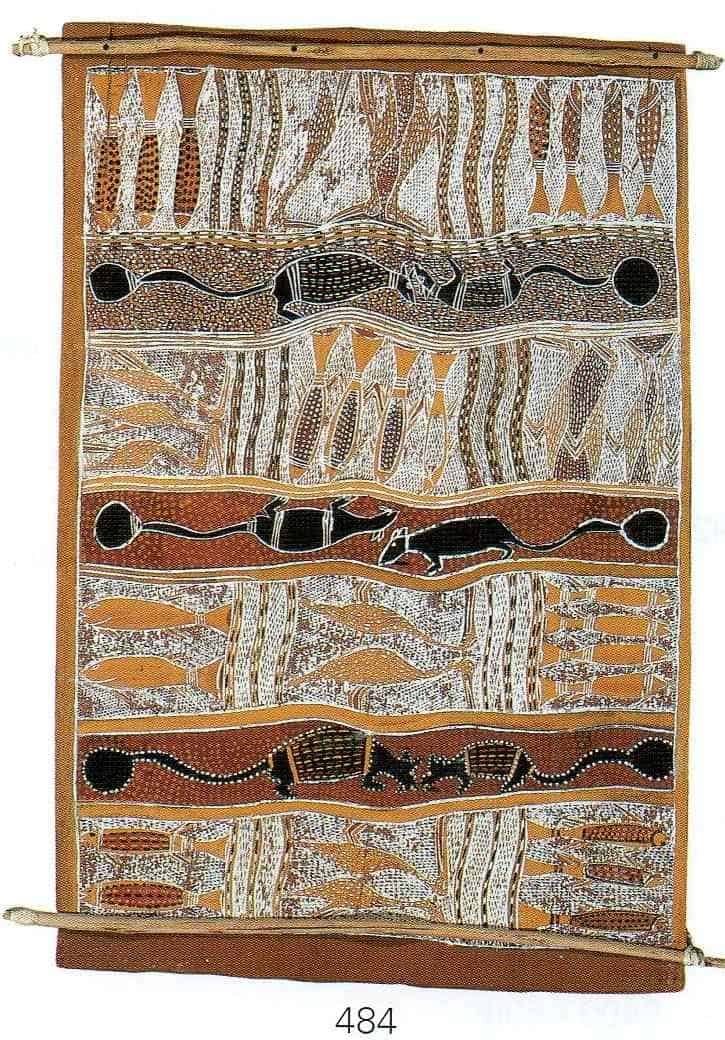

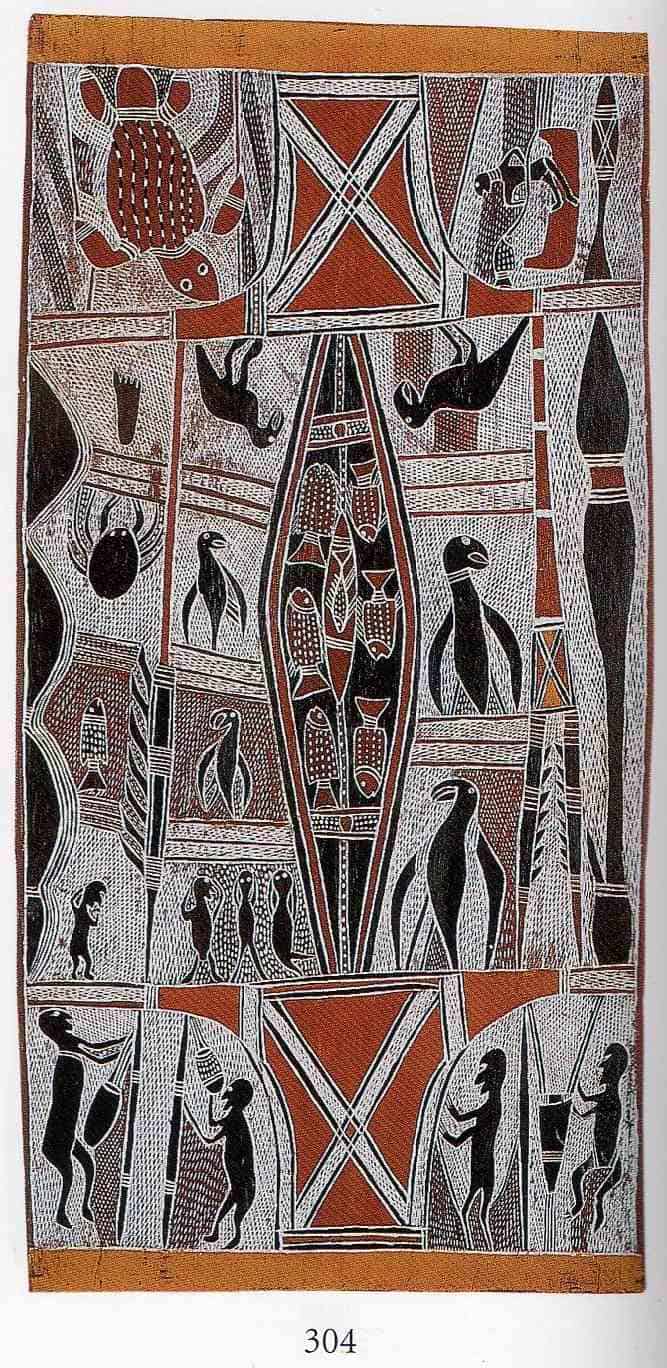

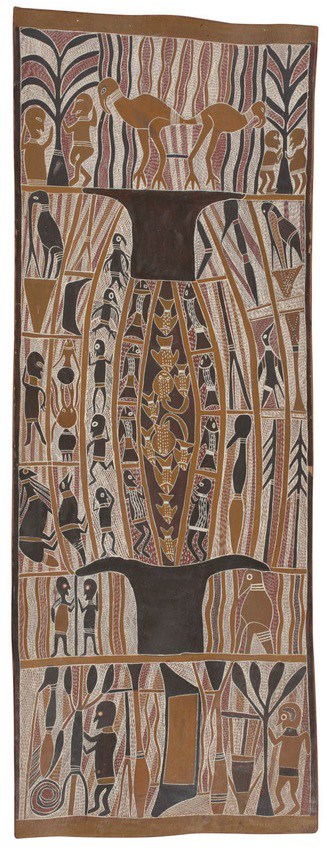

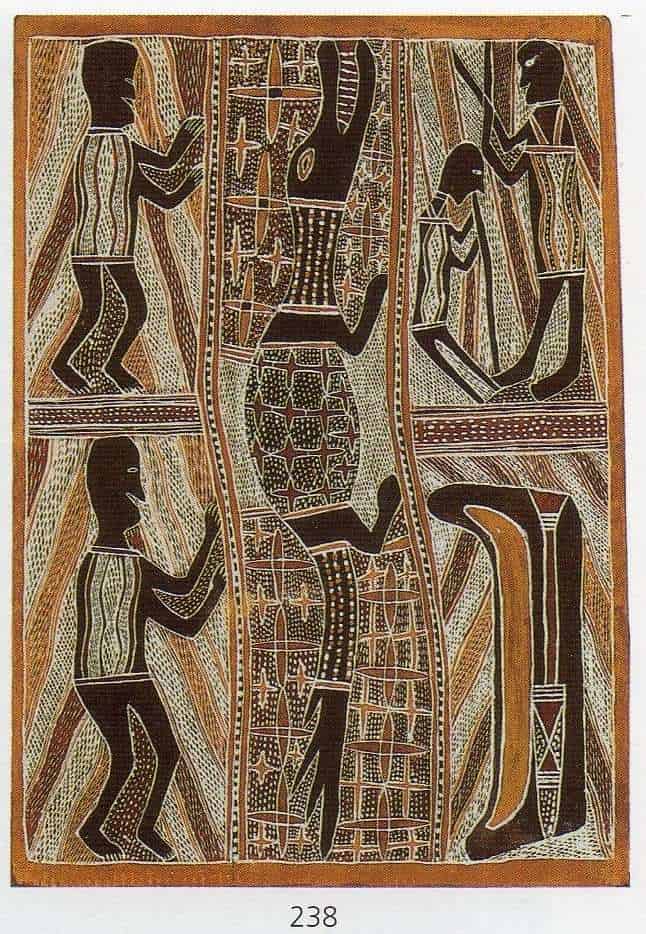

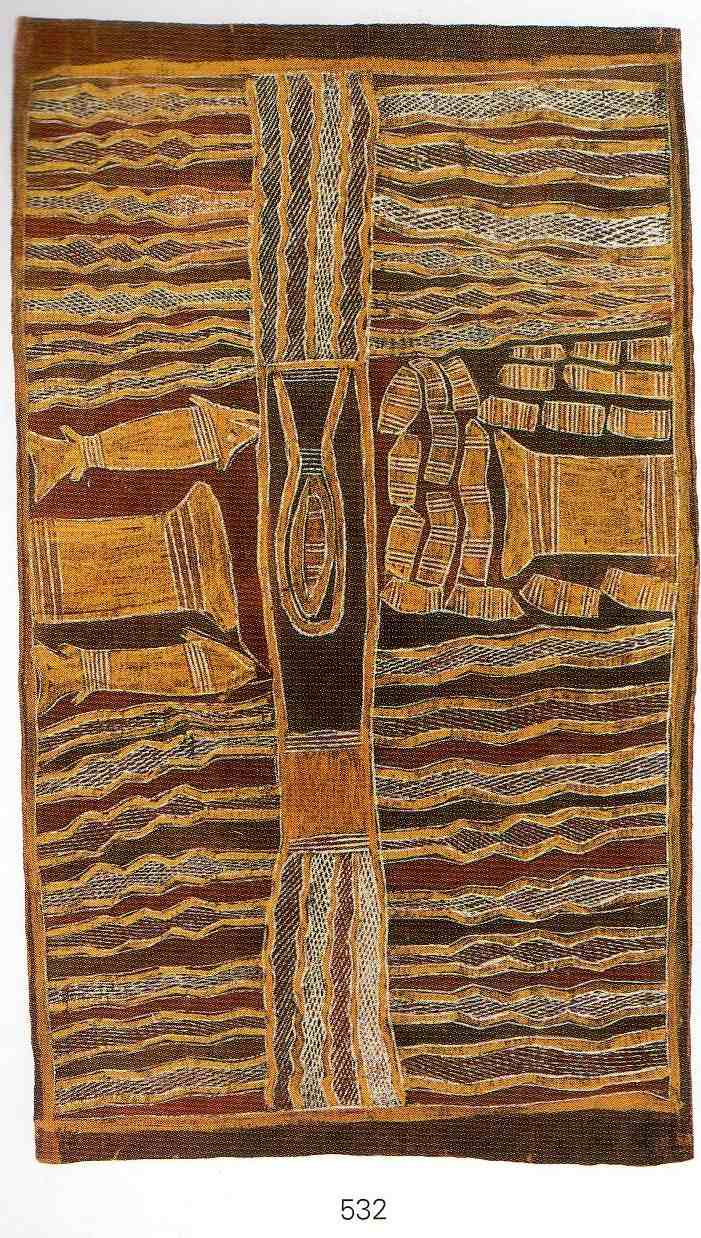

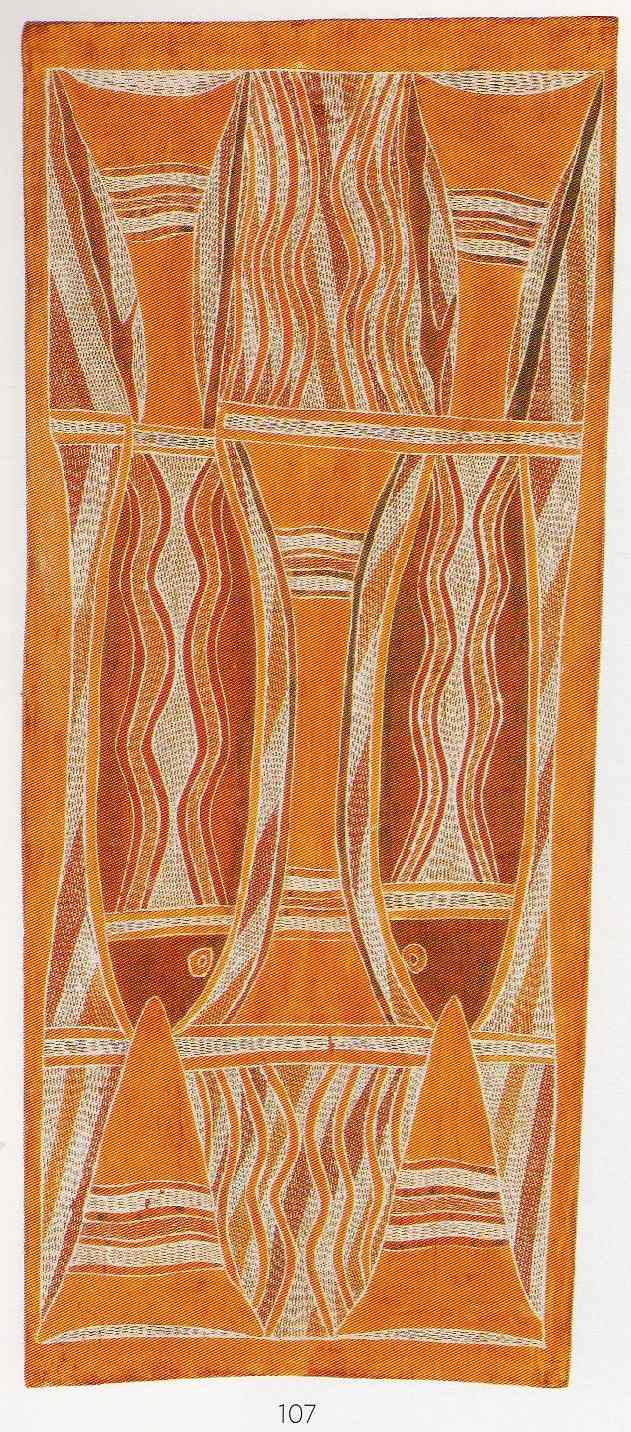

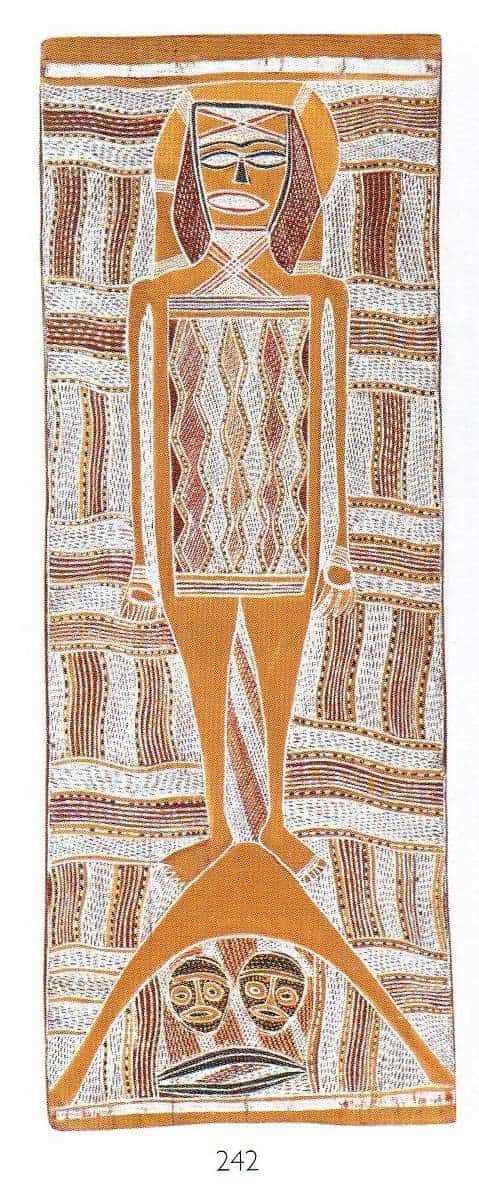

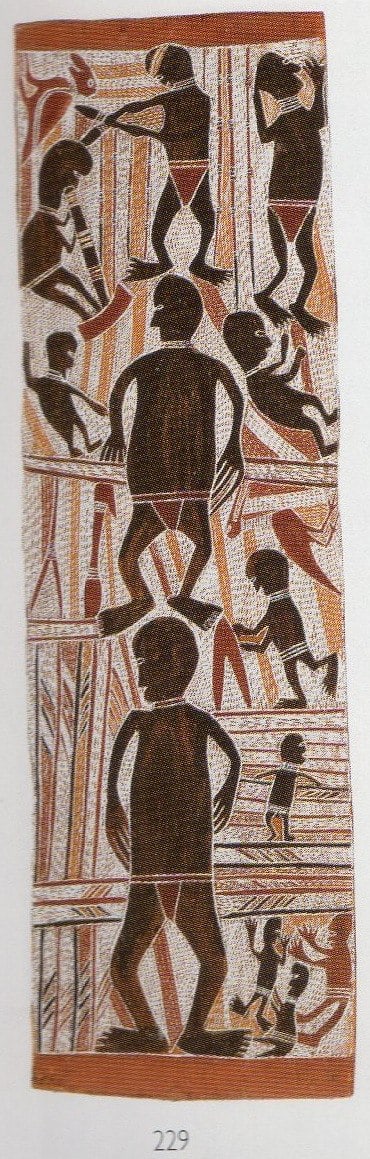

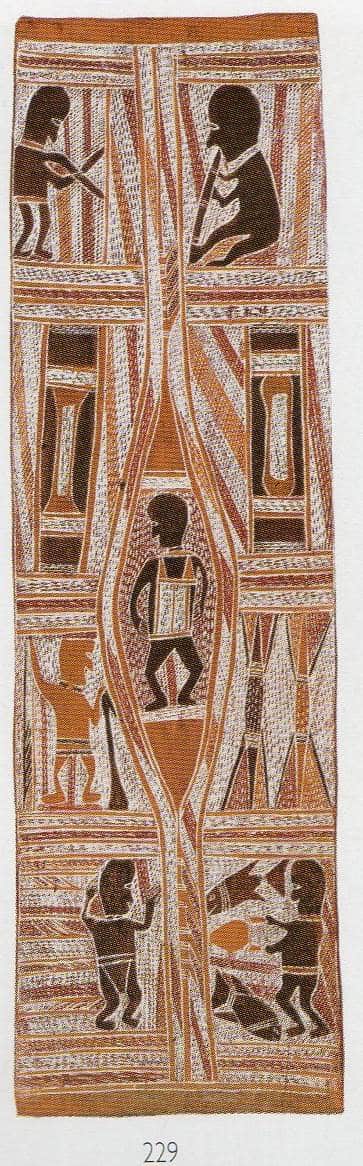

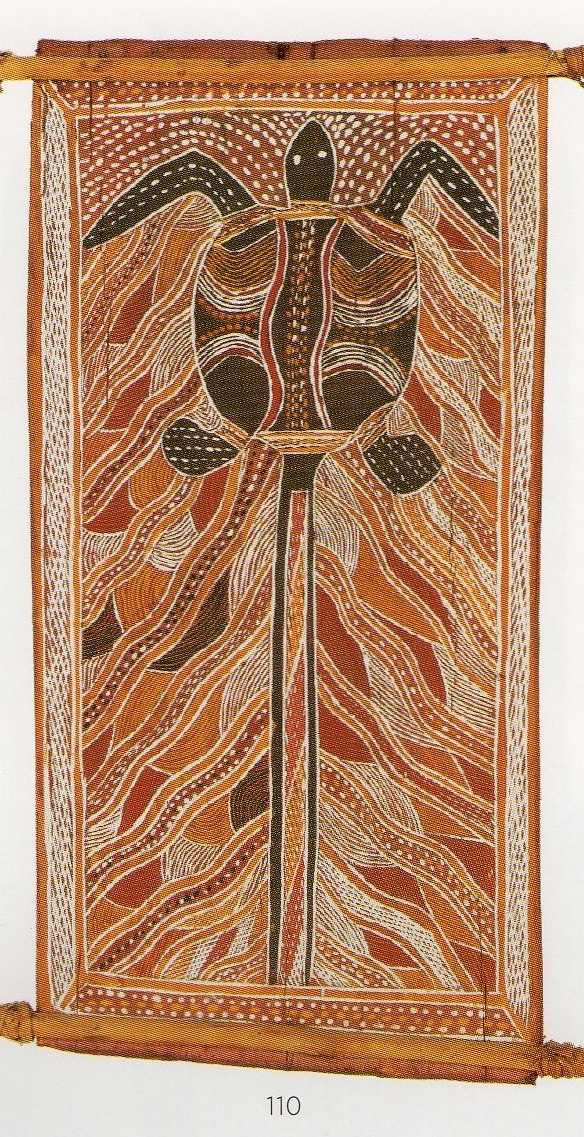

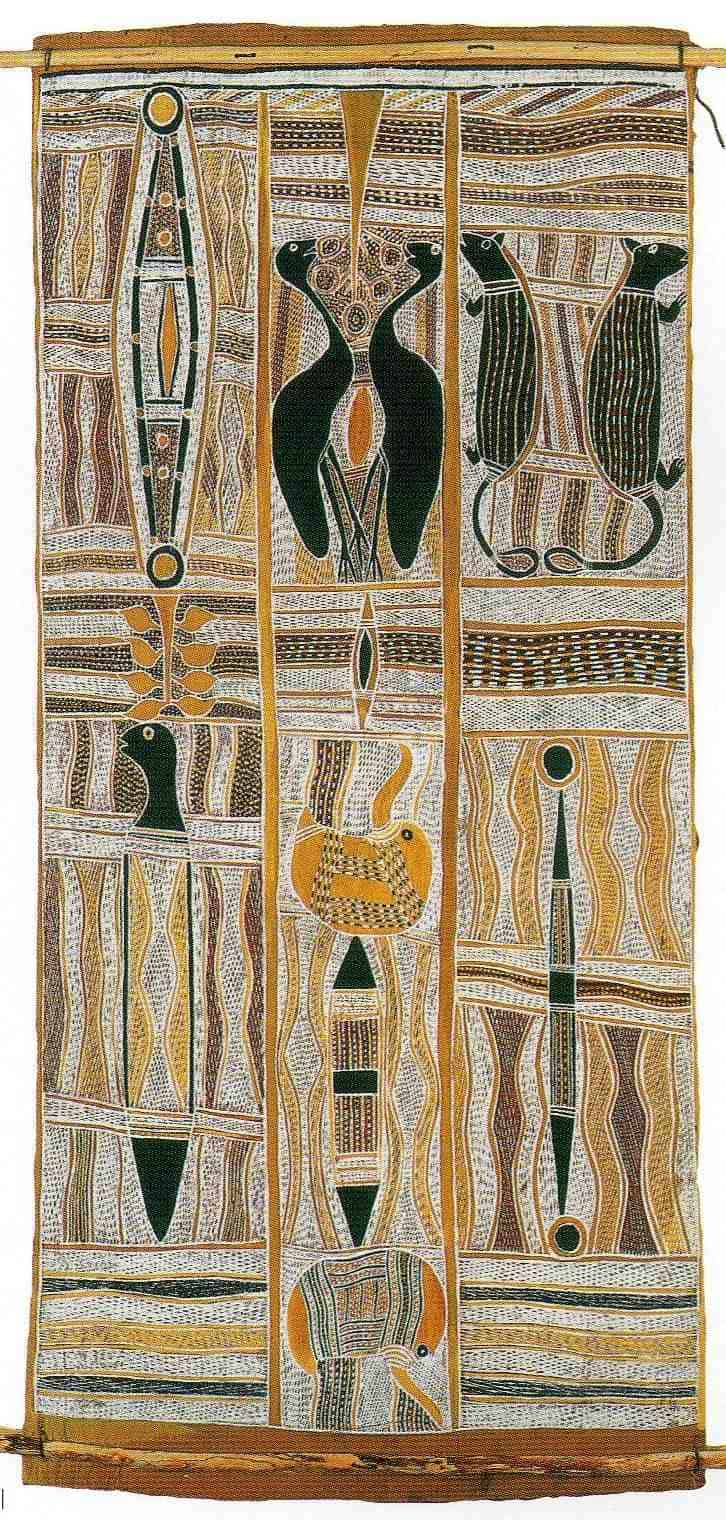

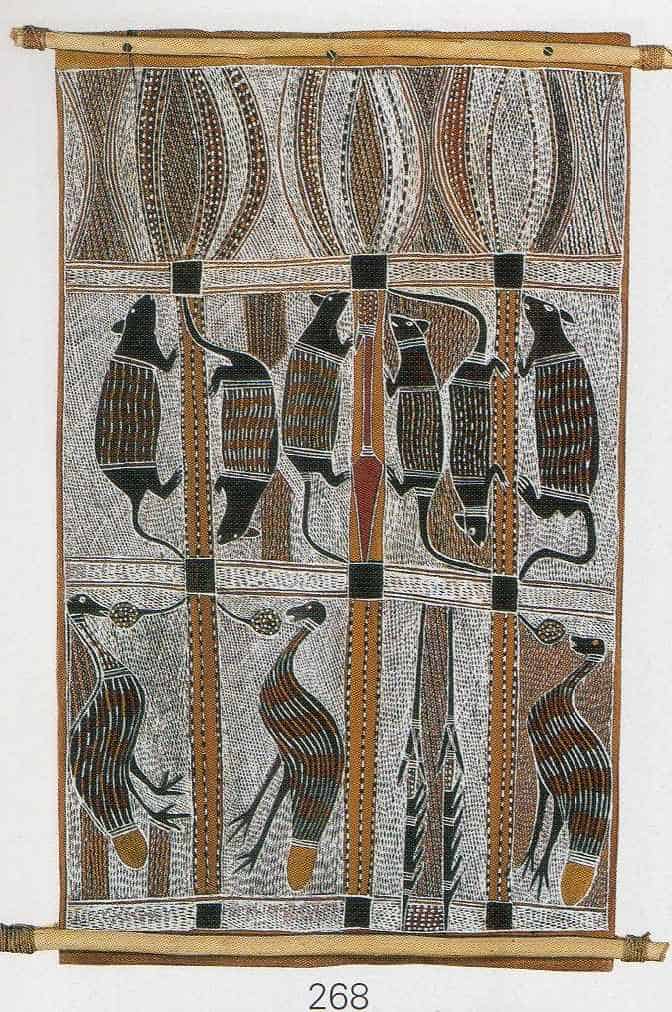

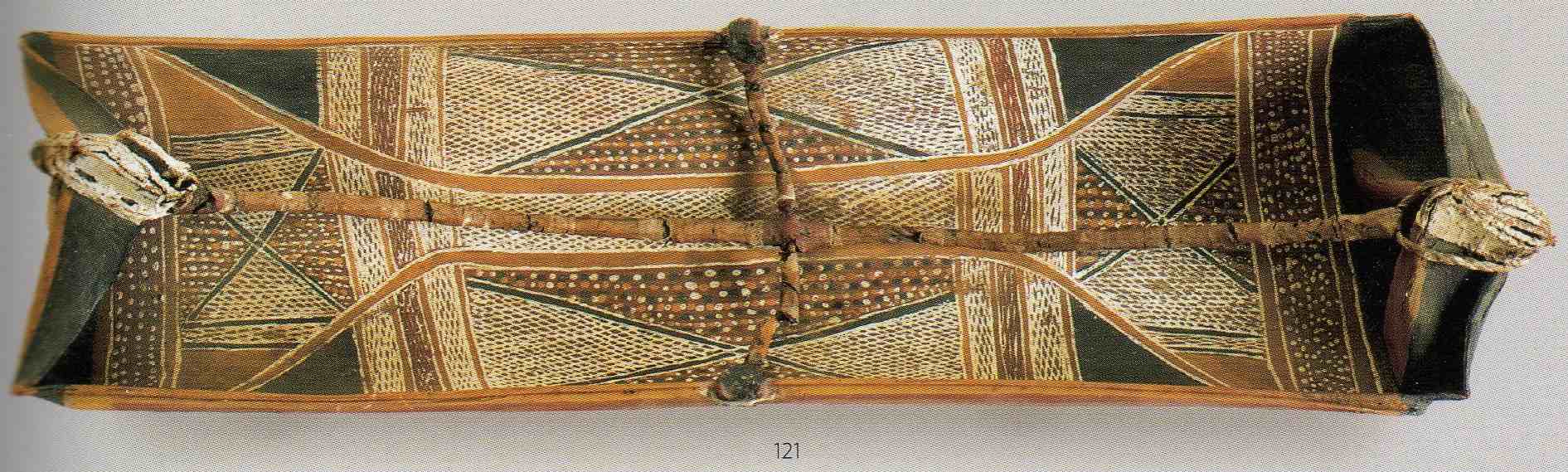

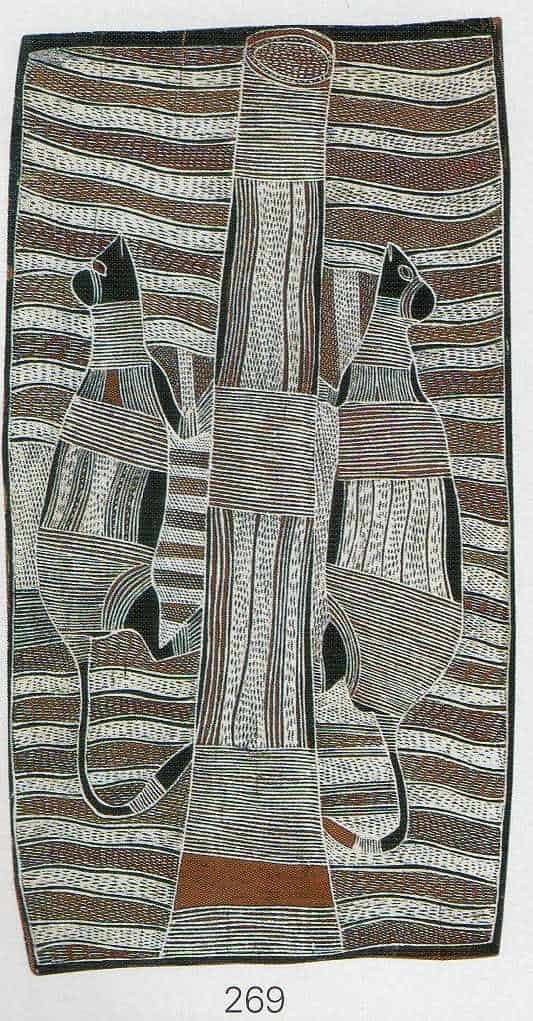

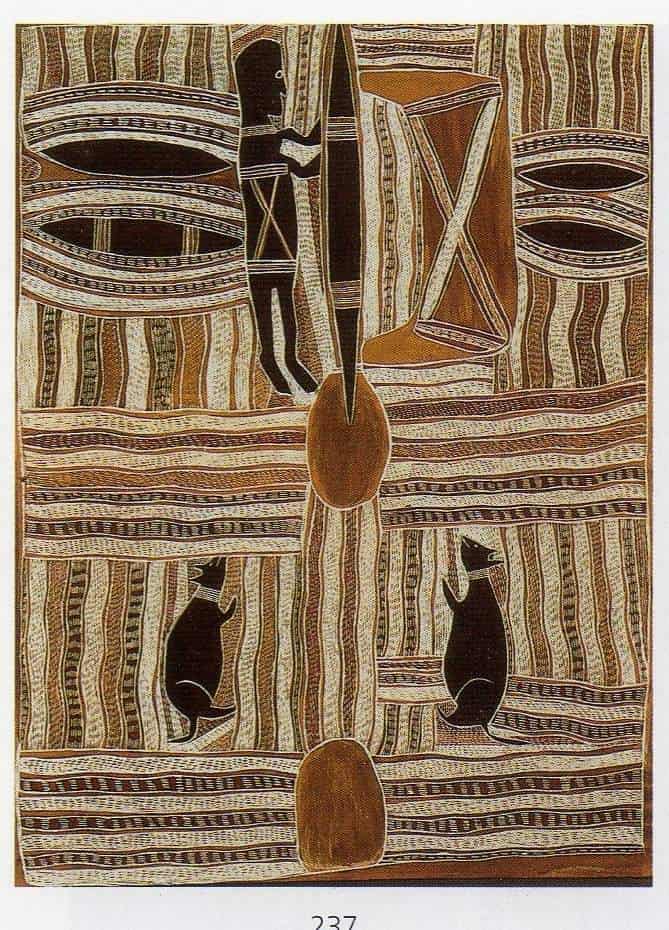

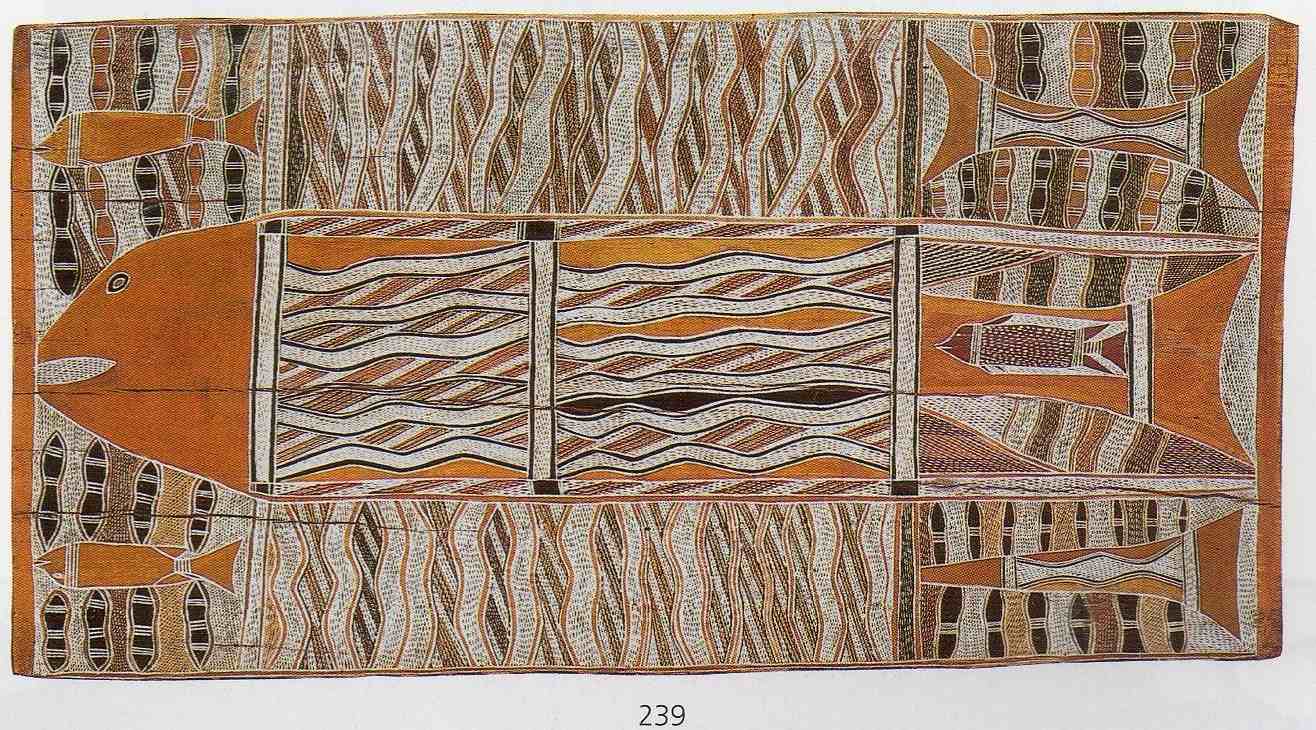

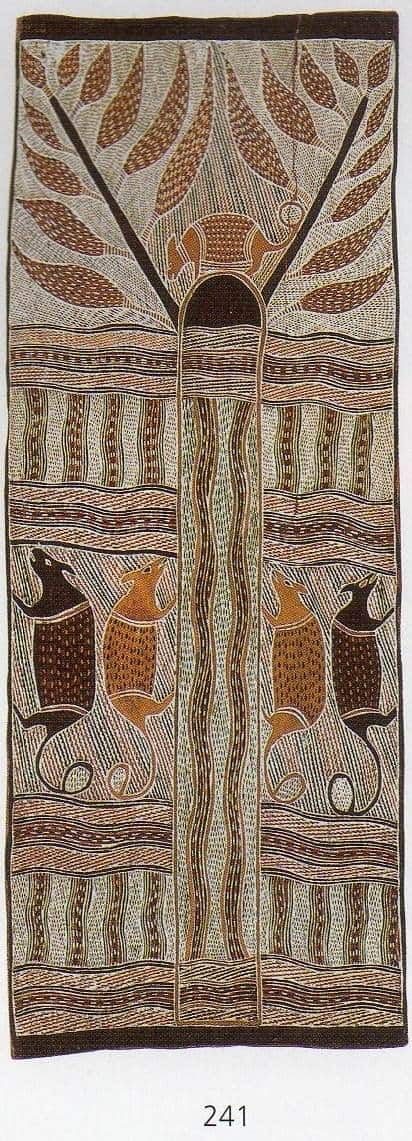

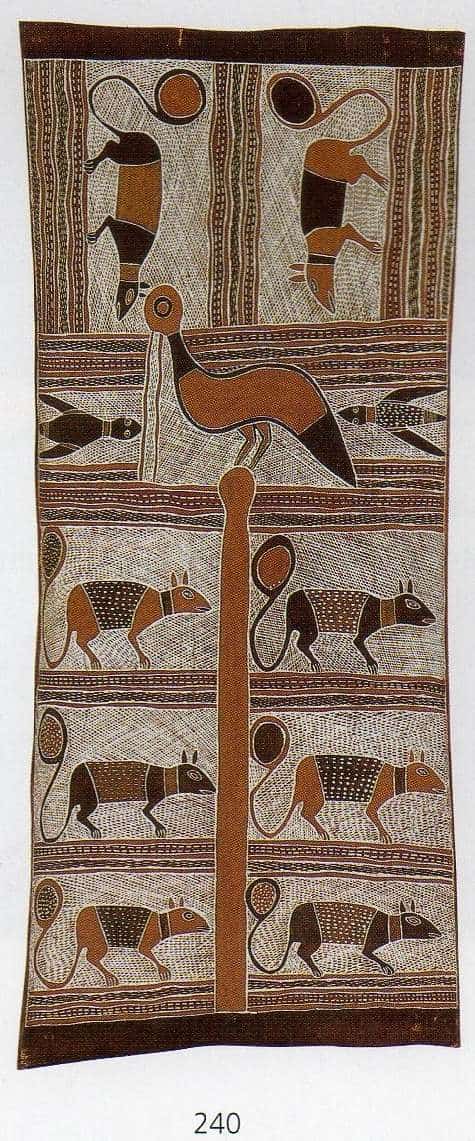

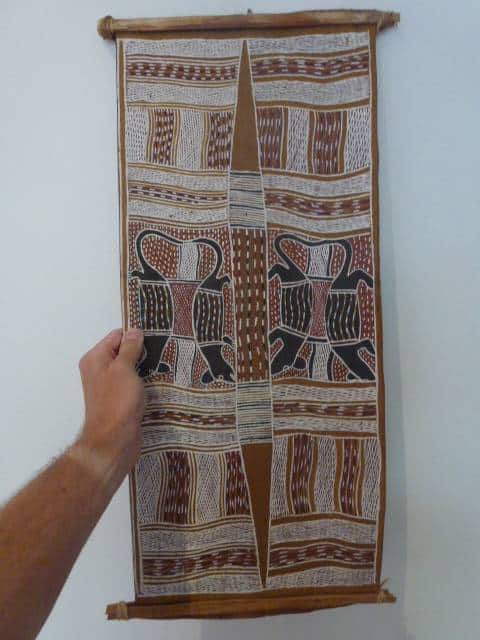

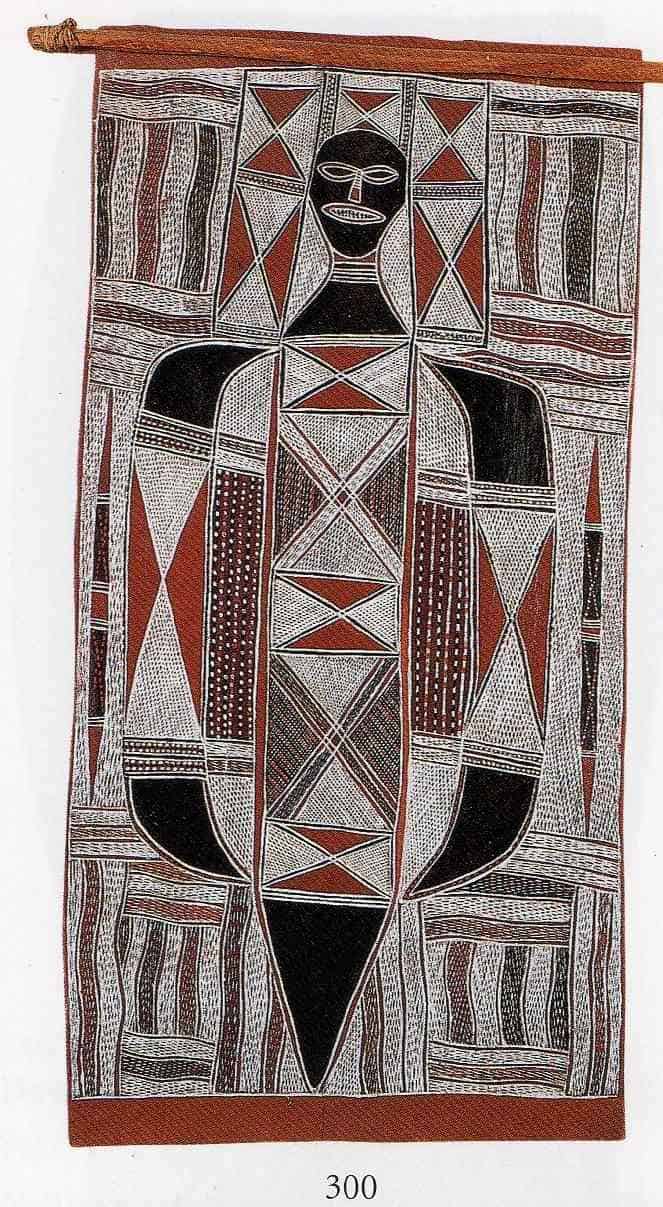

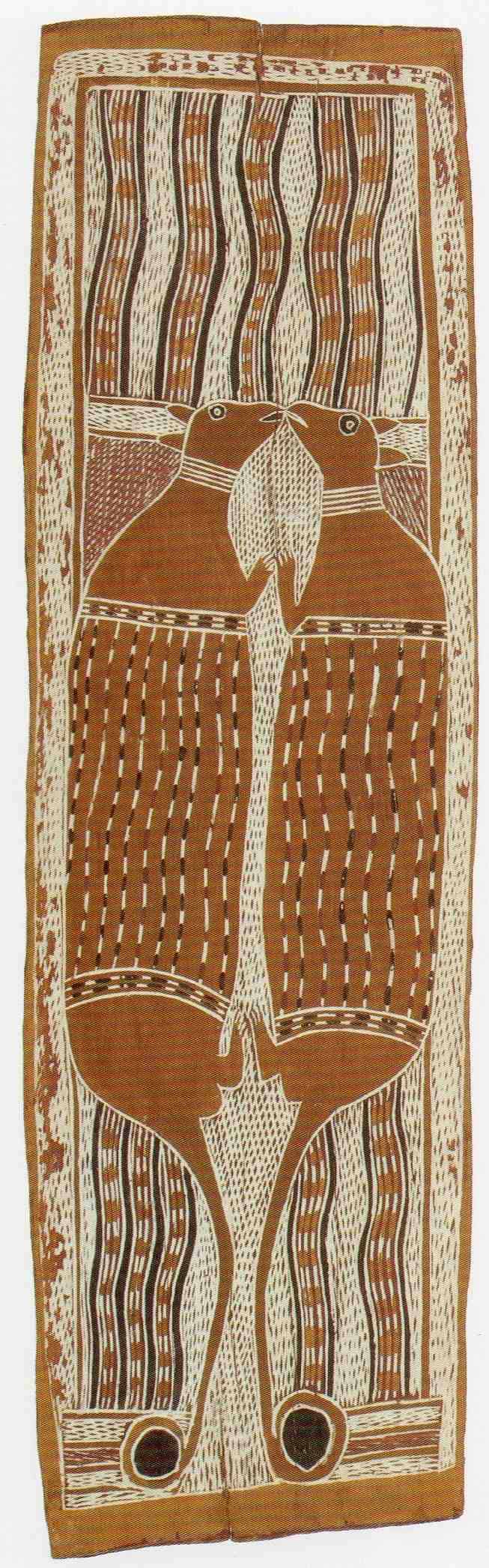

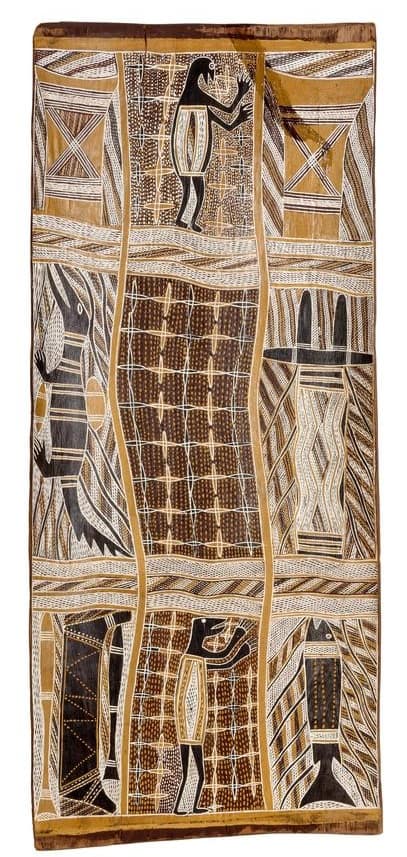

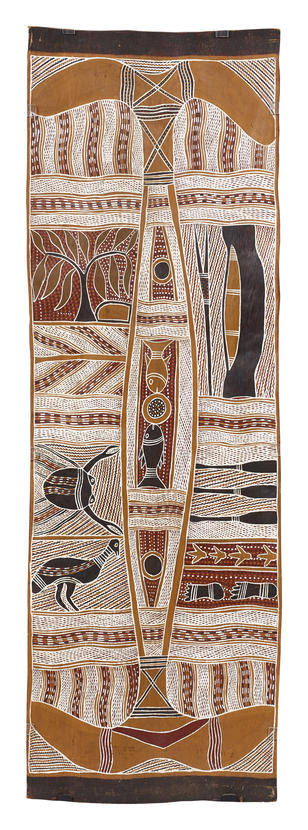

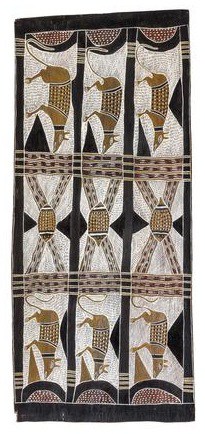

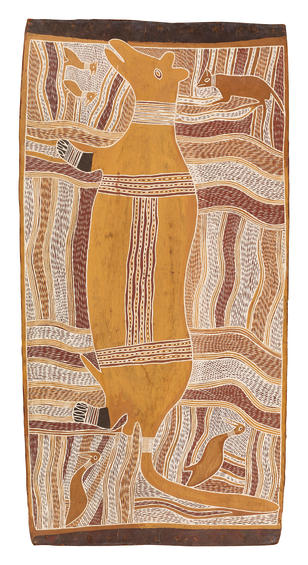

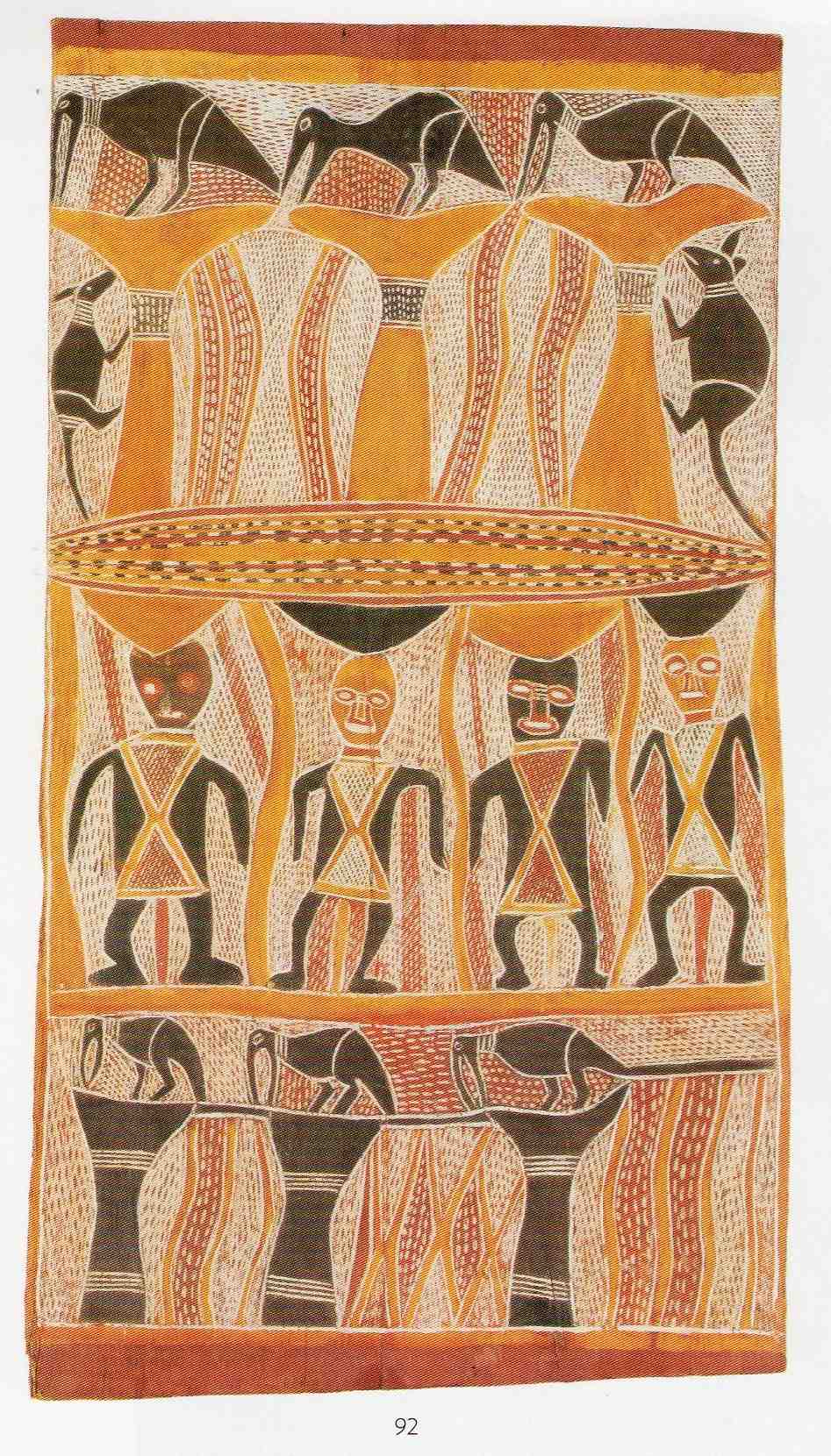

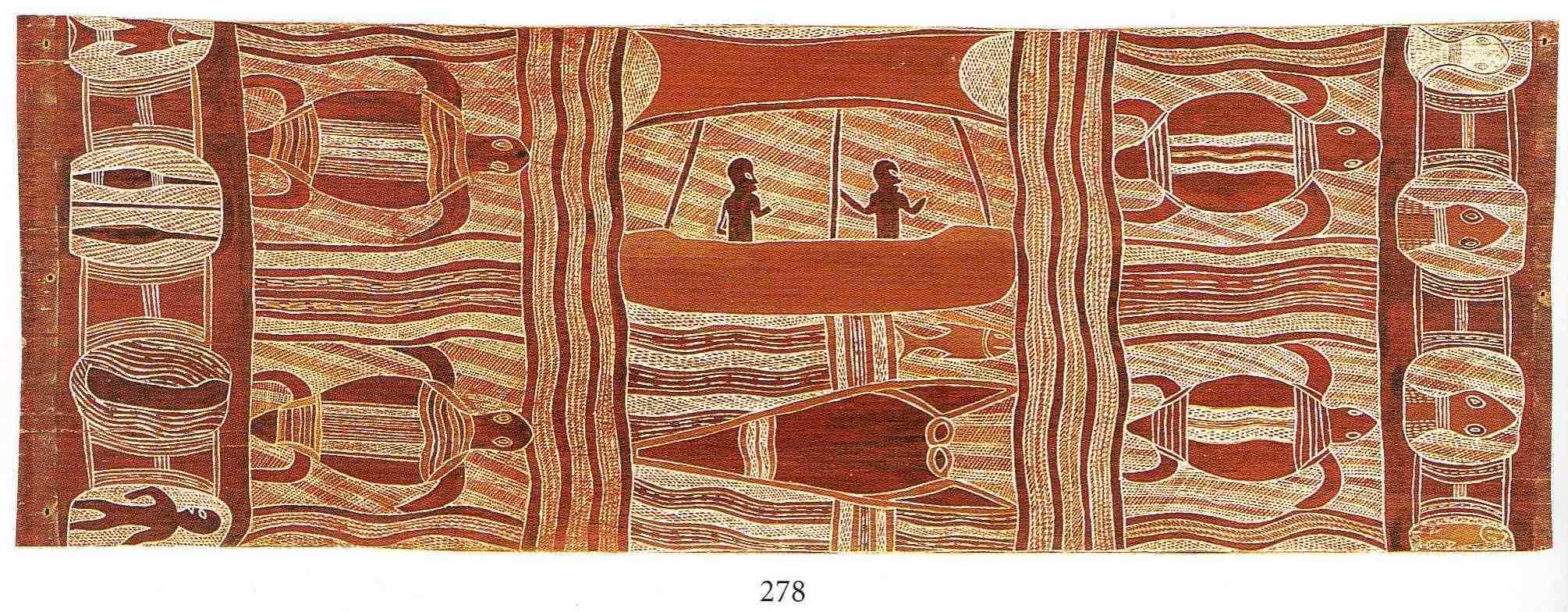

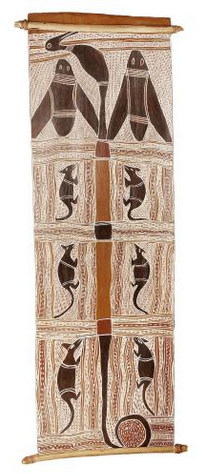

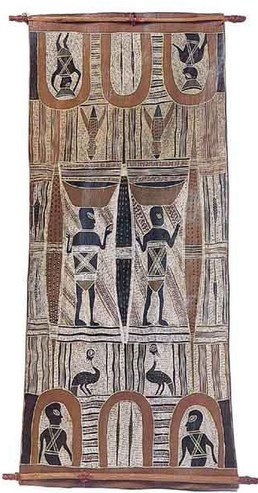

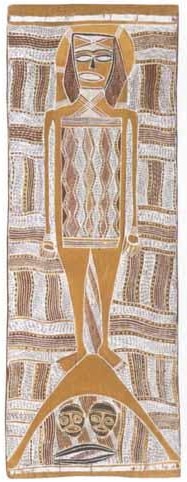

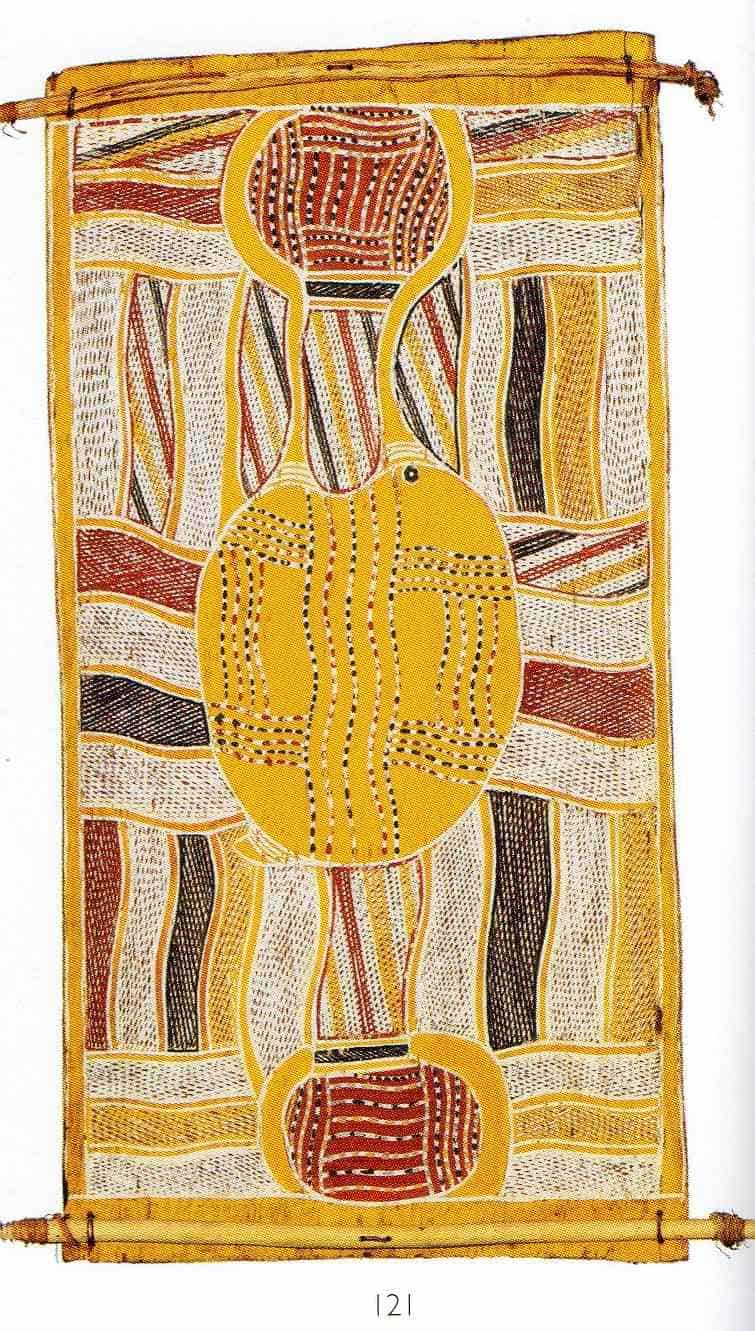

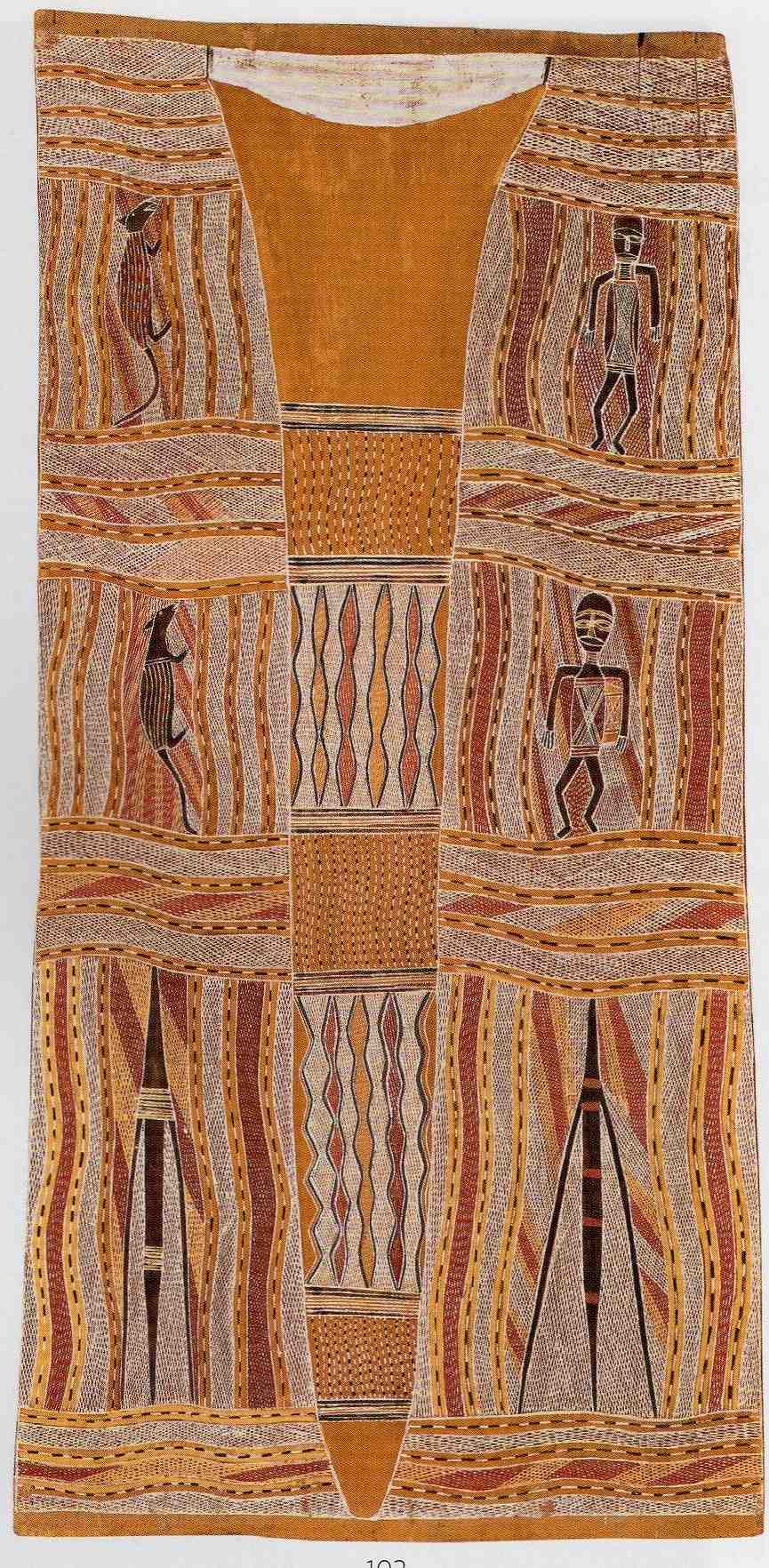

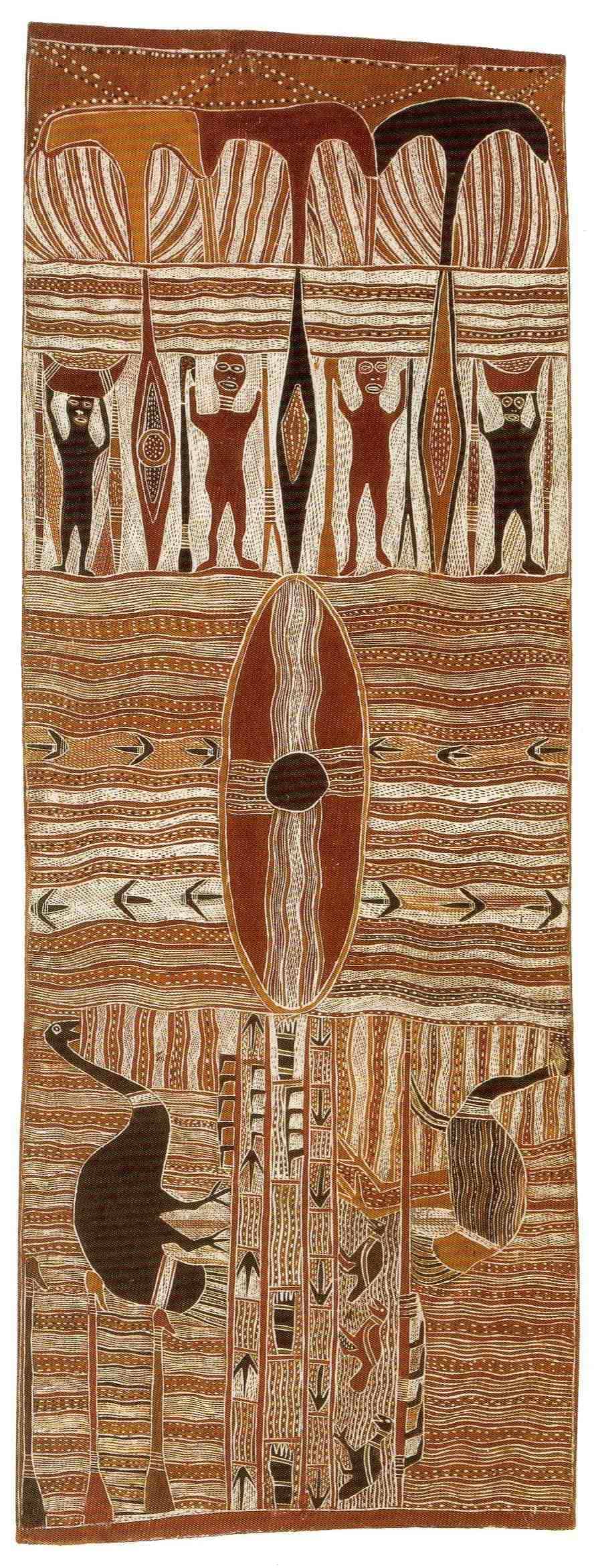

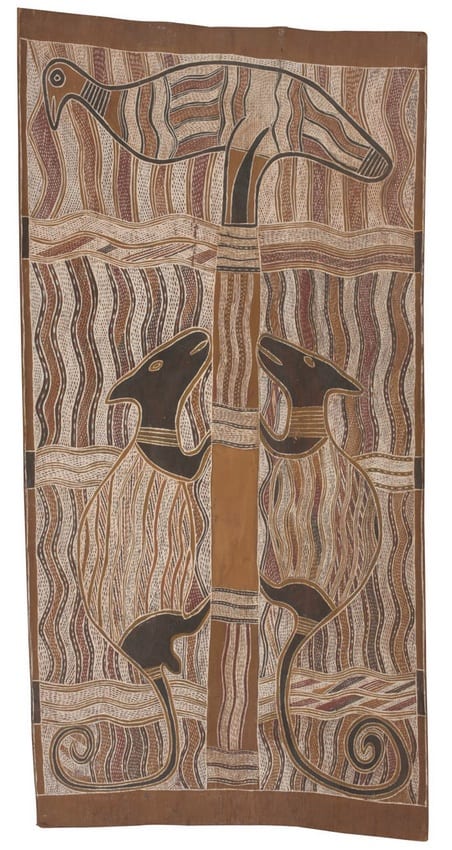

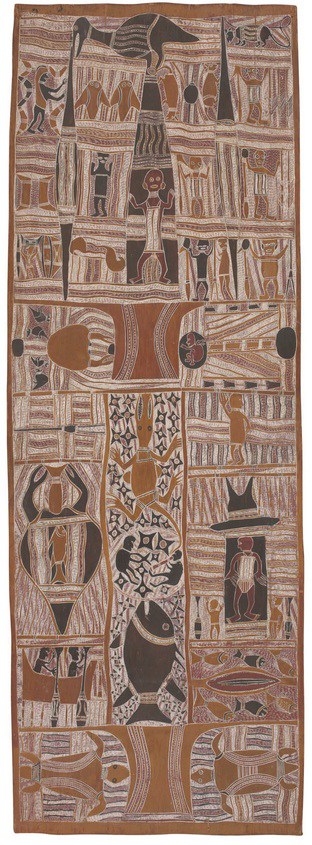

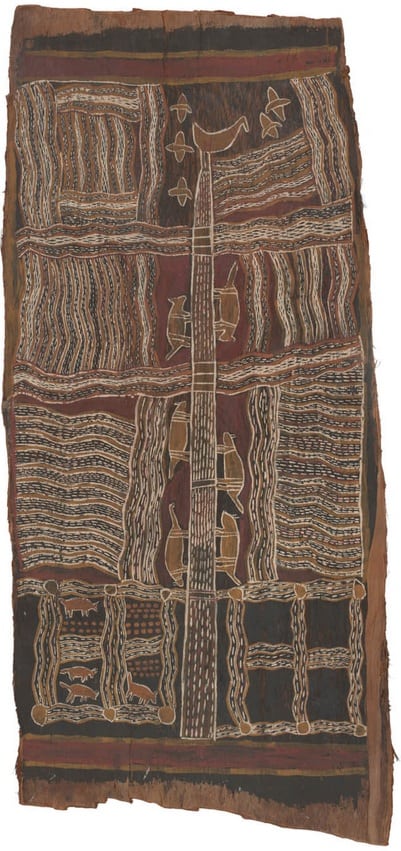

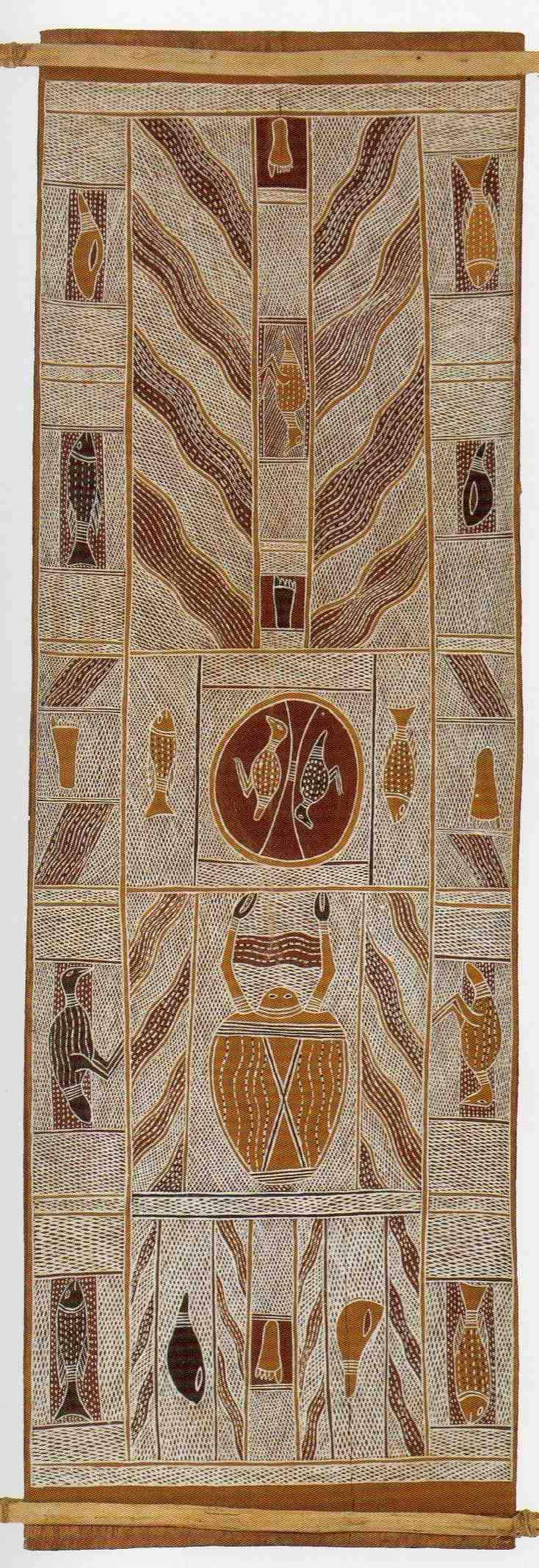

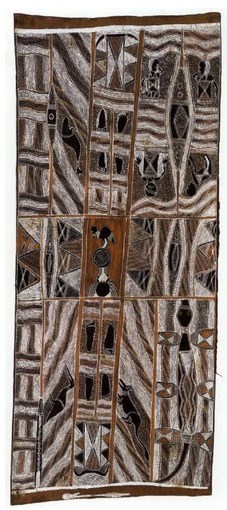

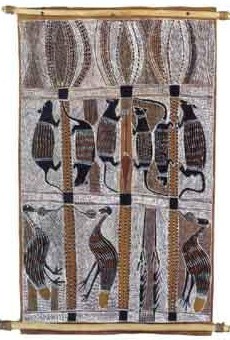

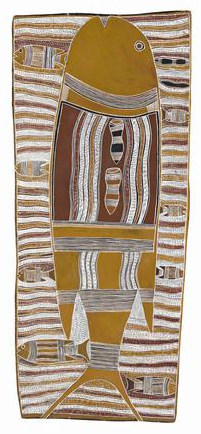

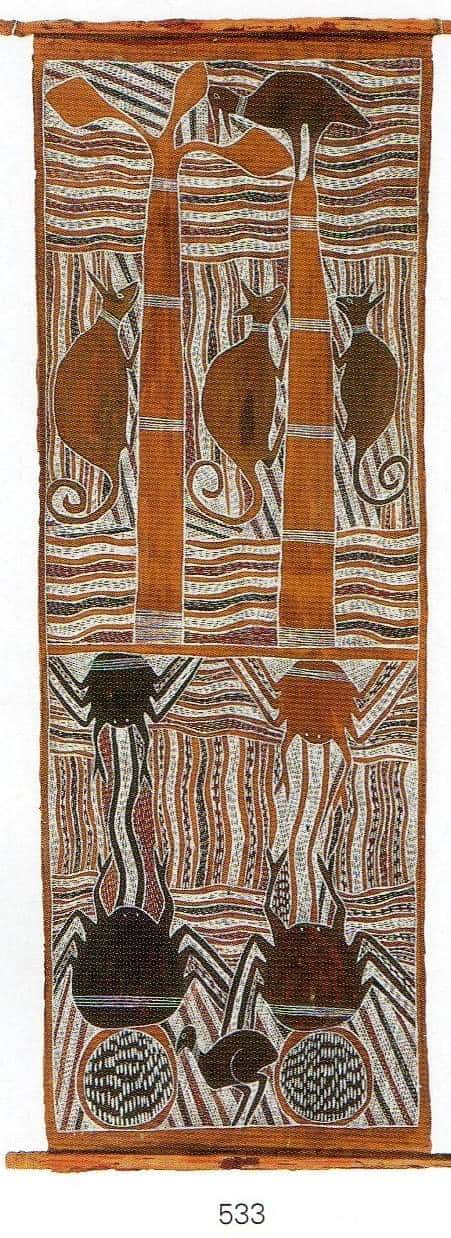

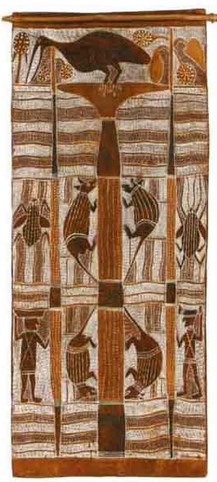

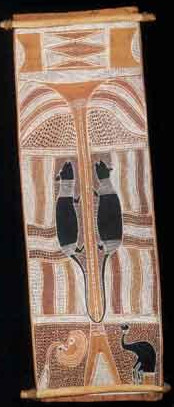

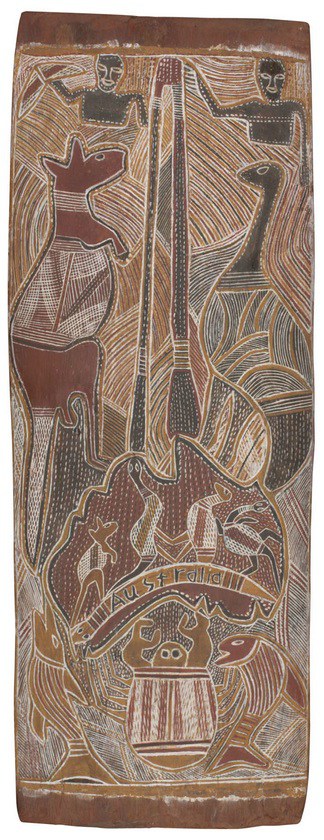

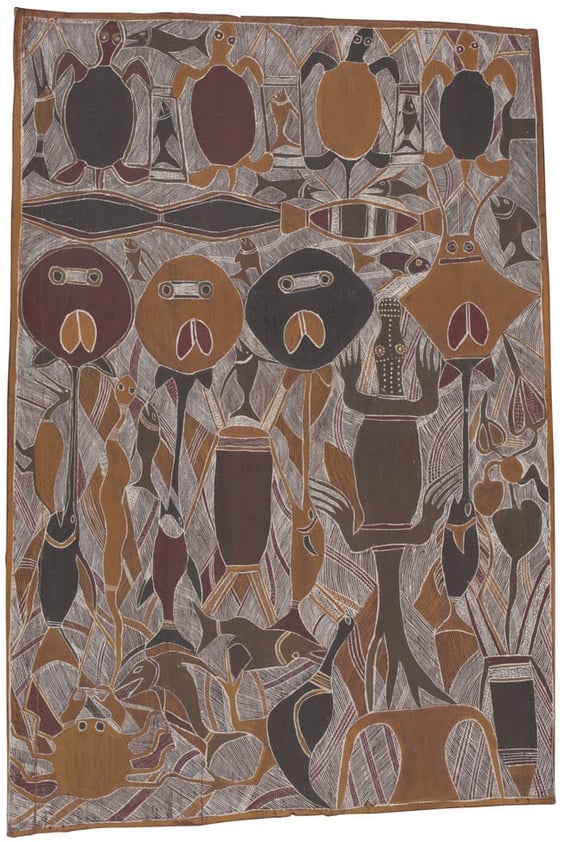

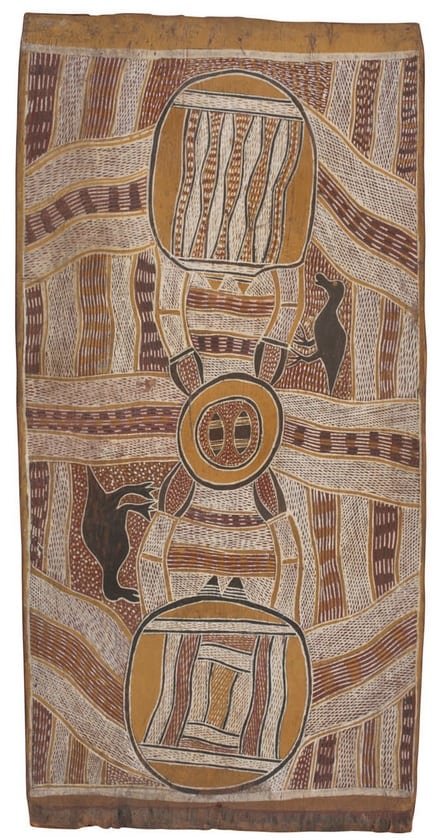

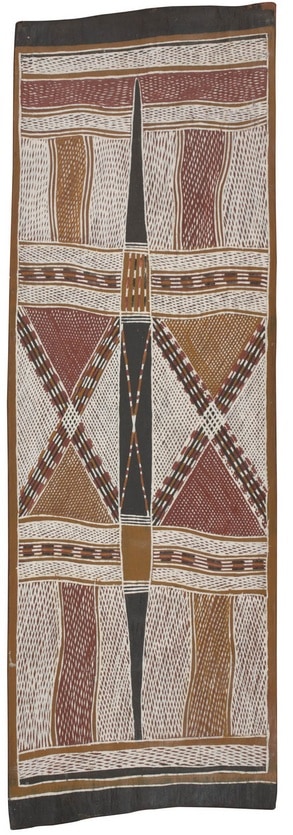

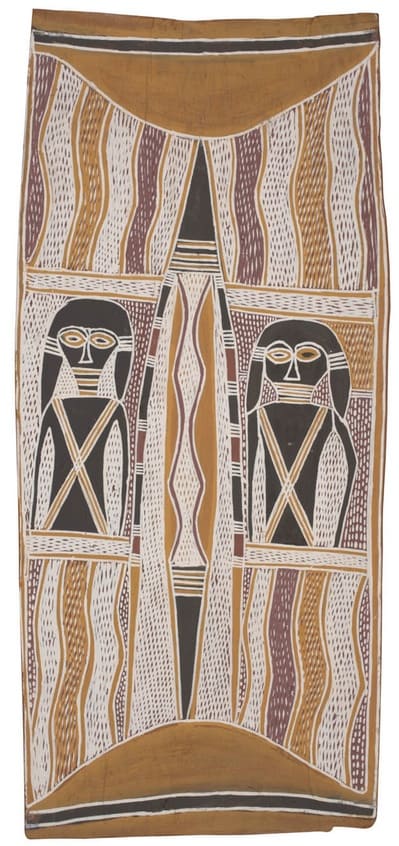

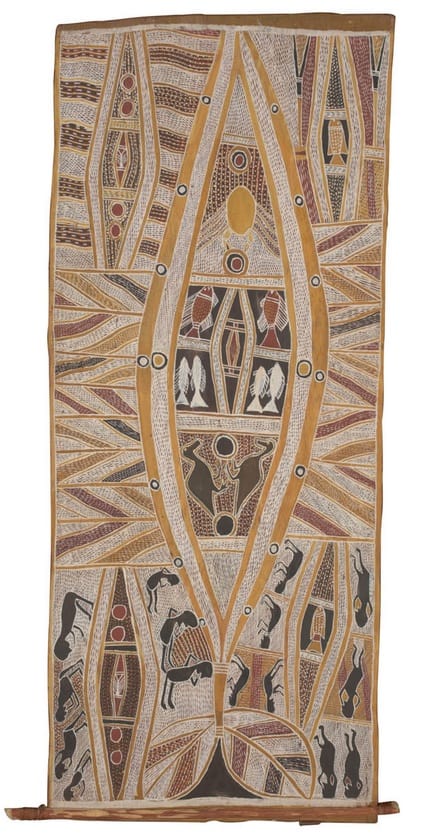

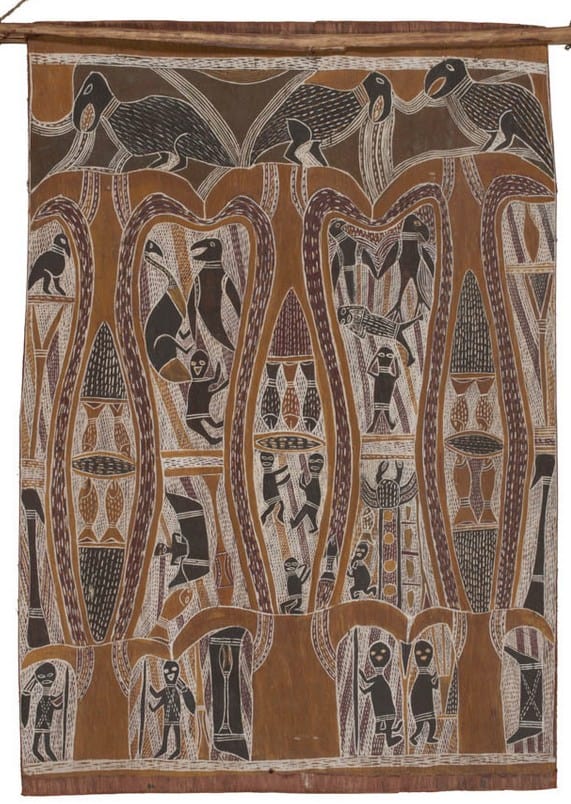

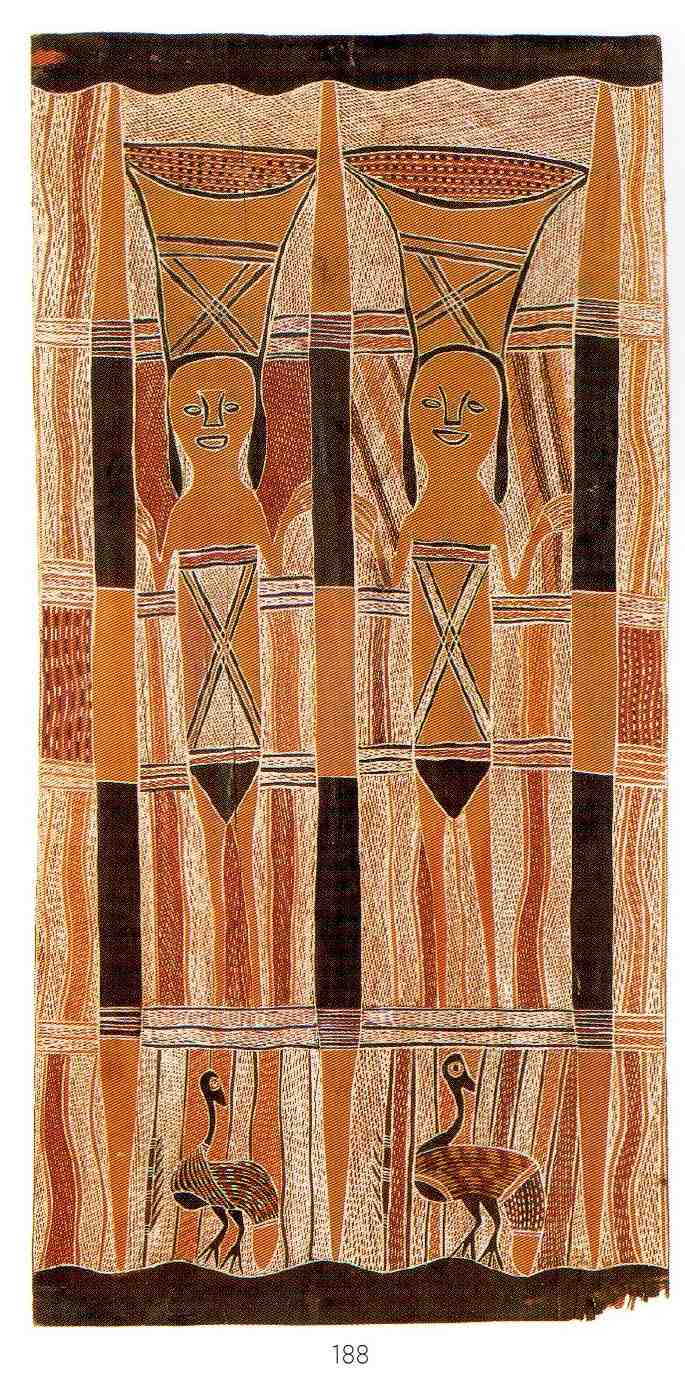

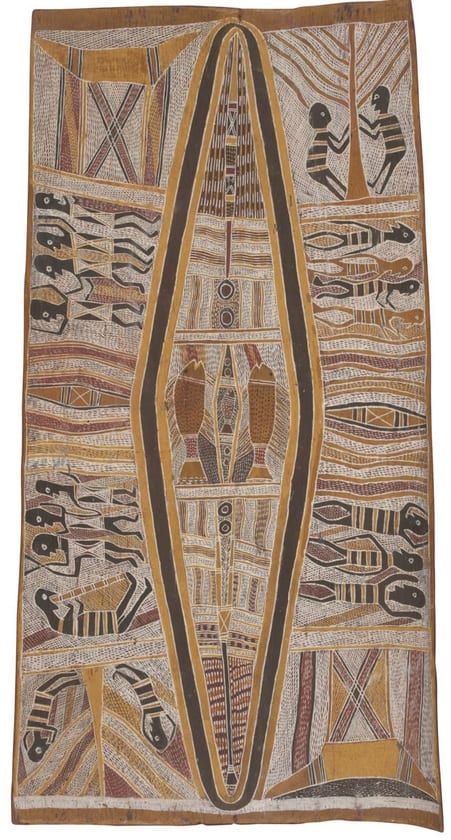

Narritjin Maymura often separated his bark paintings into schematic panels. Vertical and horizontal features separate these Schematic panels. He painted backgrounds completely in rarrk crosshatching and in traditional motifs. These motifs include diamonds, rows of dashes, anvil shapes and an X pattern. He often depicts possums. Possums relate to the Marrngu ancestral story. Marrngu was a creator ancestor of his Manggalili People.

Figures and animals on Narritjin barks have a black face and are static and formalized. Stark figurative elements contrast with the intricate background. Intense rarrk cross-hatching creates an optical clarity. Narritjin continued to use a human-hair brush and natural ochre long after alternatives were available.

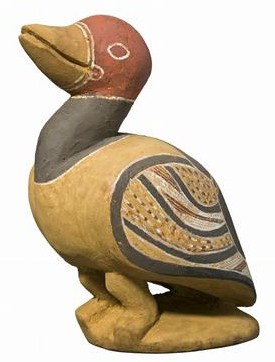

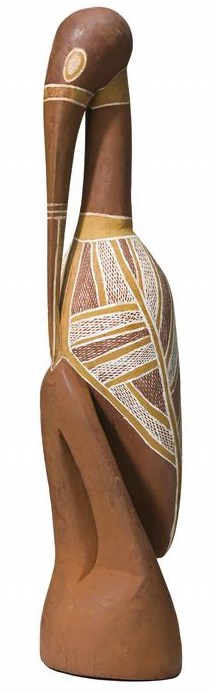

Maymura has also done a few East Arnhem Land sculptures but they are not as collectible as his bark painting.

Biography

Narritjin spent his early years hunting and gathering in East Arnhem Land. He lived in the area between Blue Mud Bay and Caledon Bay. As a young man worked with Fred Gray in the trepang industry. Narritjin moved to Yirrkala Mission soon after its establishment in 1935. He was one of the first Yolngu people to become a Christian. Narritjin worked with the missionaries to bring peace to the Yolngu. He negotiated peace and stopped them fighting among themselves. Narittjun Maymuru first learned to paint from his father Lotama Guthitjpuy. He was later taught to paint by his maternal grandfather Birrikitji. He tried to educate his children in both the old and the new ways. In the mid-1970’s he worked hard to establish an outstation for his family at Djarrakpi Cape Shield.

He taught all his children, both boys, and girls, to do bark painting. Many of his children have become successful artists in their own right. Narritjin always tried to convey to non-Aboriginal Australians respect for Yolngu culture. His art ties Yolngu culture to the land. His older brother Nanyin was also a bark painter

A man of great traditional wisdom and known amongst his people as Guduwurru, (the western equivalent would be a philosopher). He assisted Birrikitji and Munggurrawuy Yunupingu with painting the Yirritja church panels. The church panels are now housed in the Buku-Larrnggay Museum.

Other artists involved in painting the church panels include Wandjuk Marika, Mawalan Marika and Mithinarri Gurruwiwi

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Yirrkala Artworks and Articles

Narritjin Maymura Bark Painting Images

The following images are not a complete list of his bark painting. They do however give a very good idea of the style and variety of the artist