Munggurrawuy Yunipingu Yirrkala Bark Painter

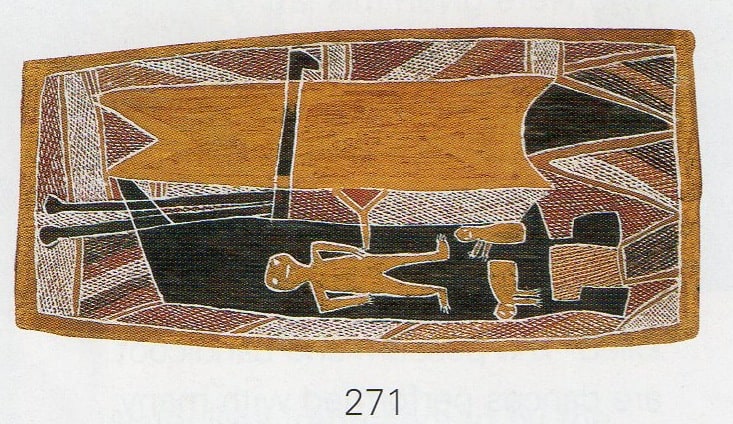

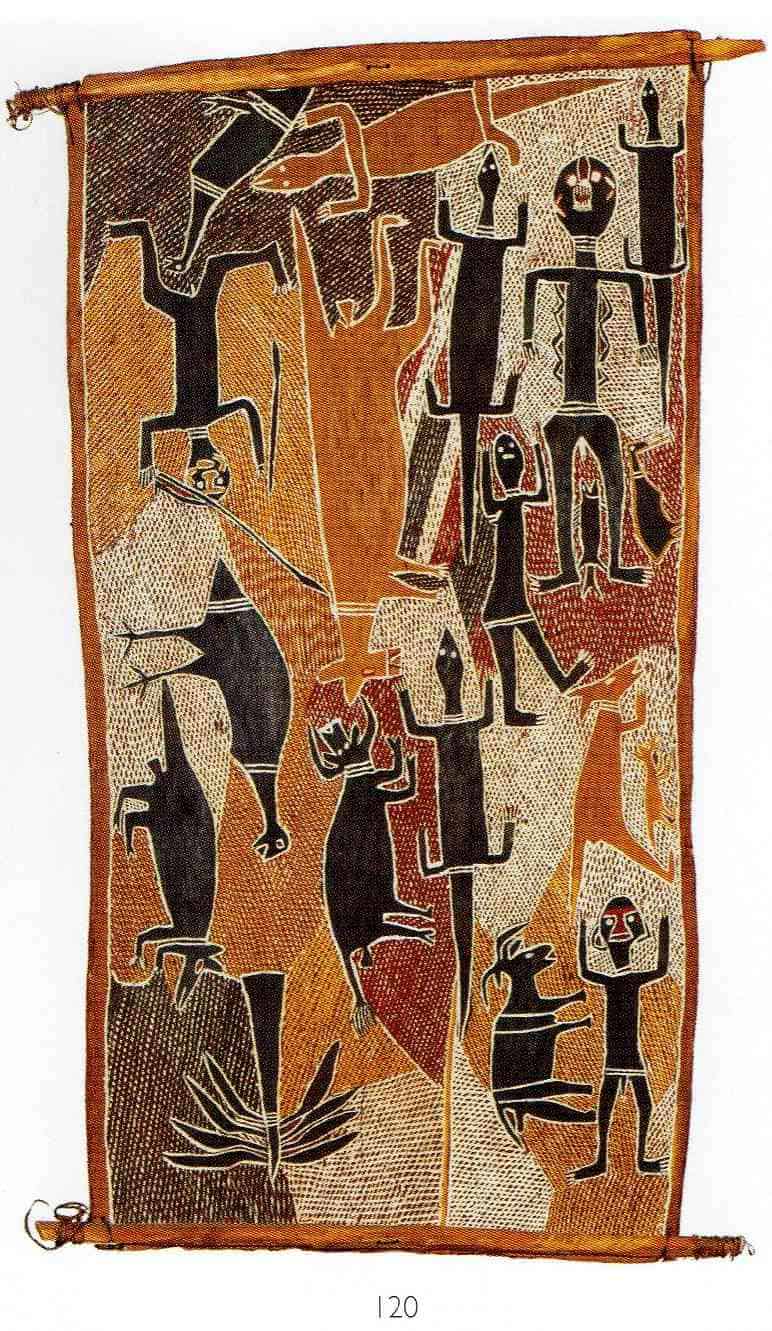

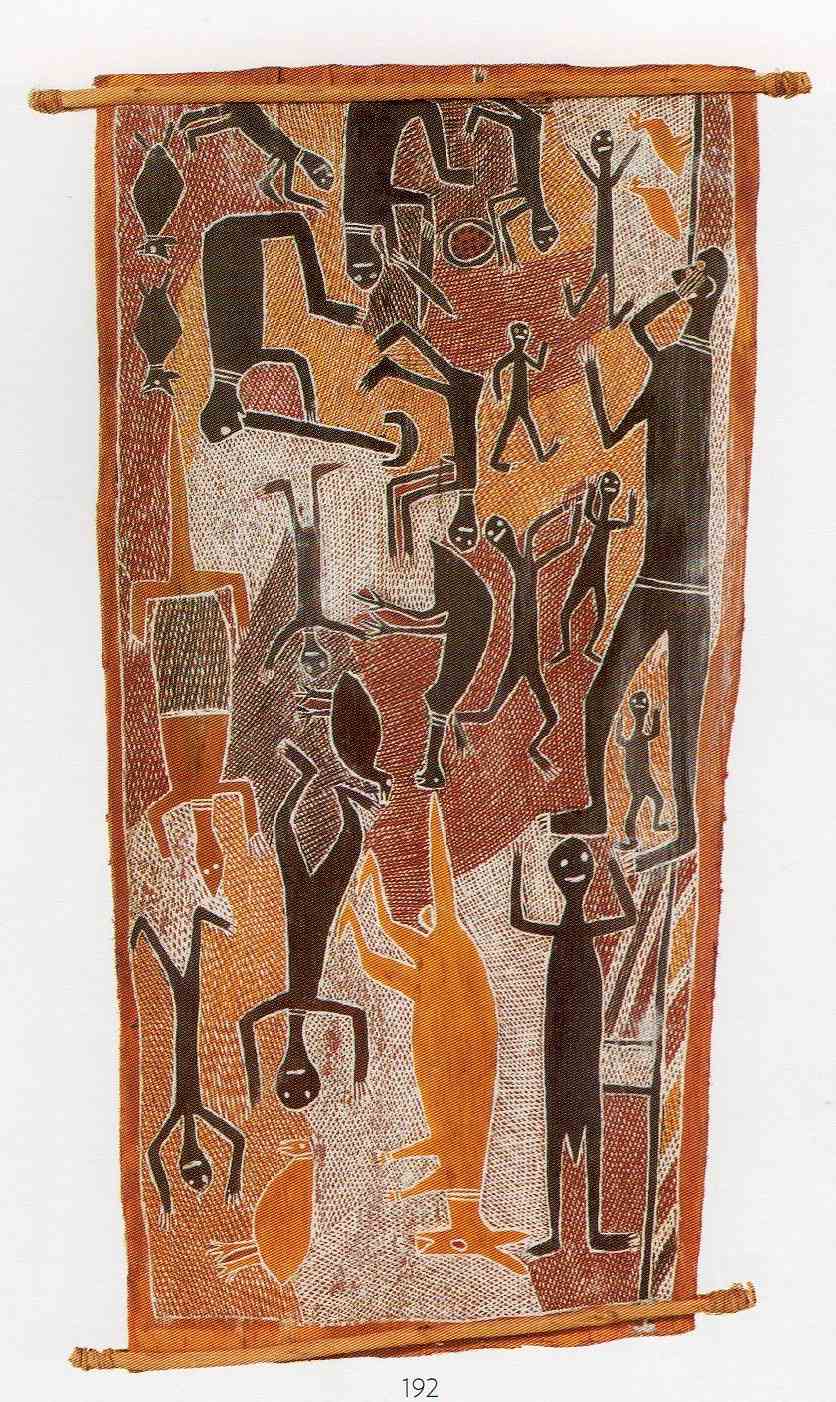

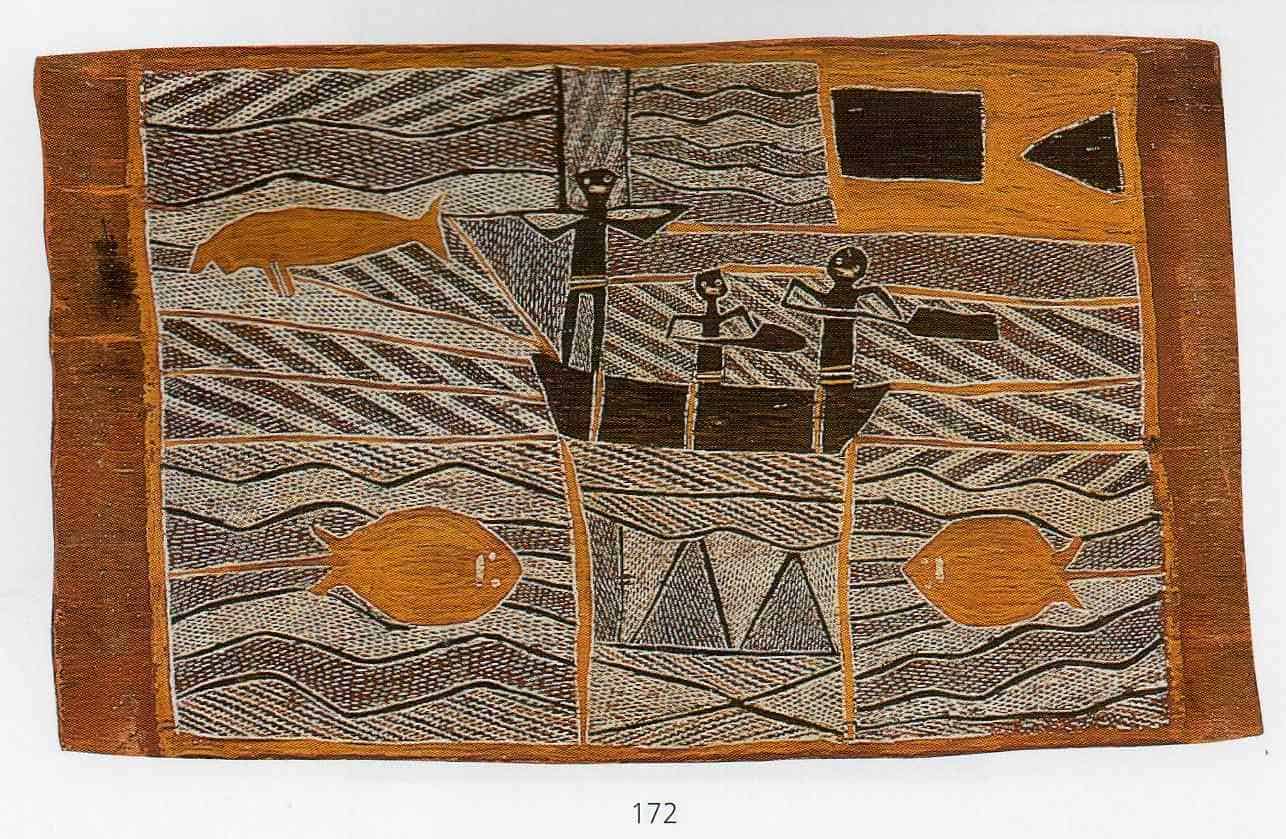

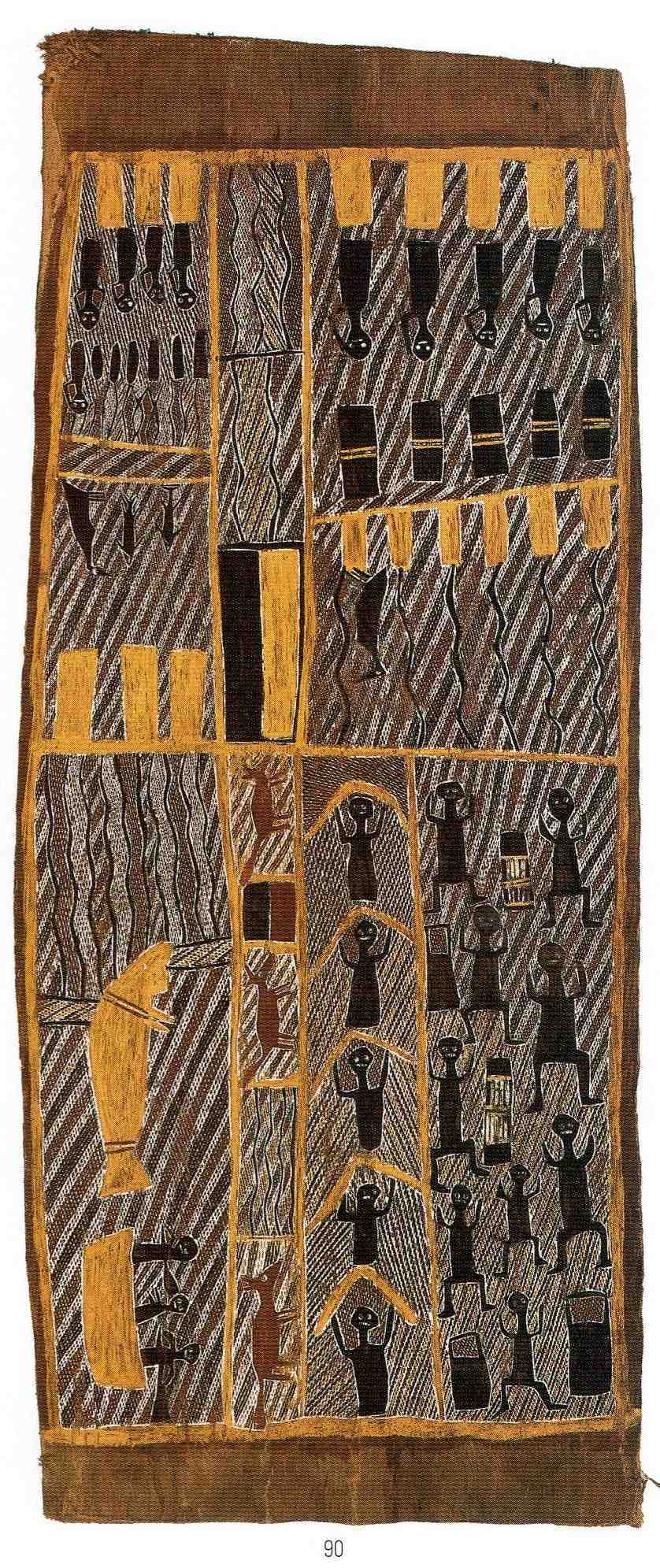

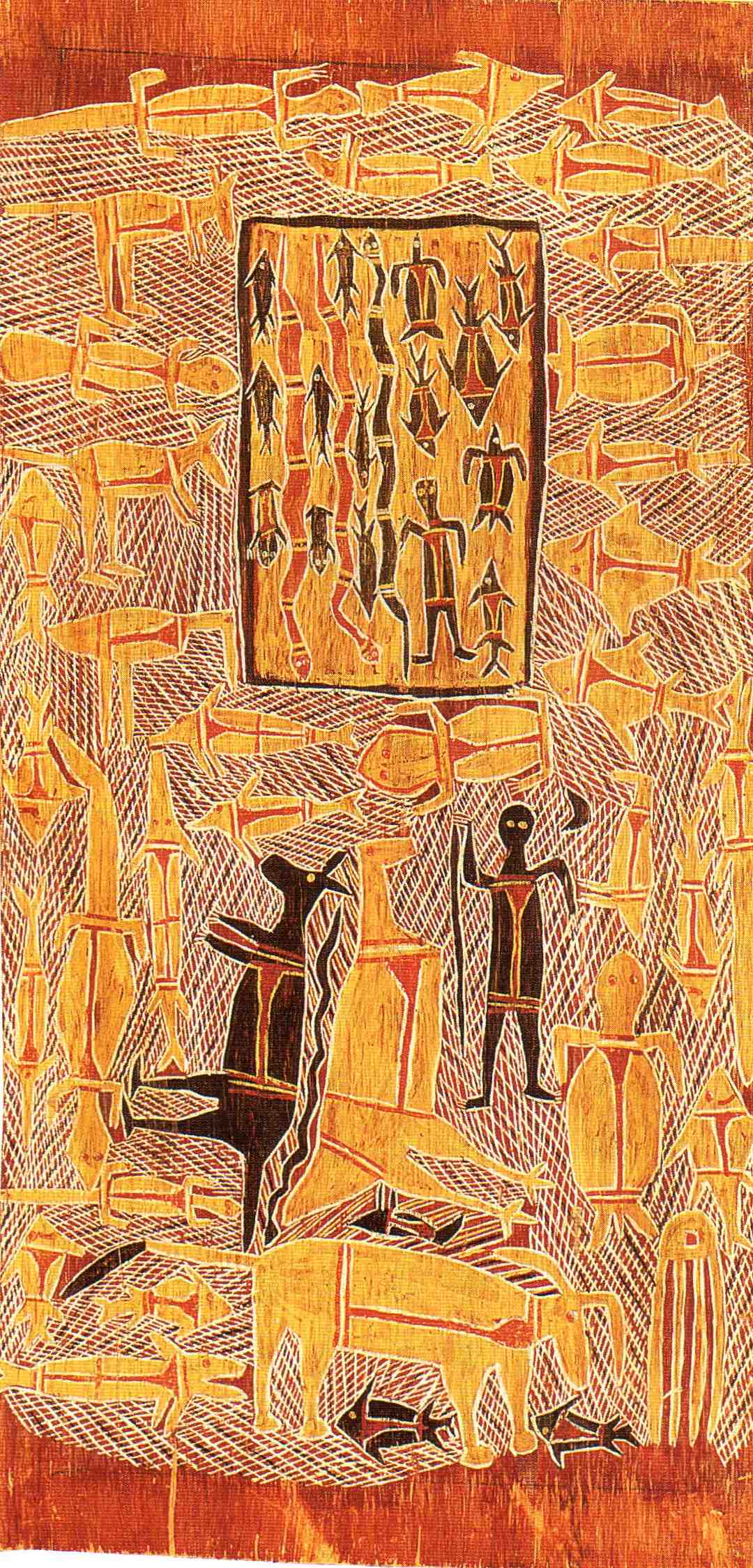

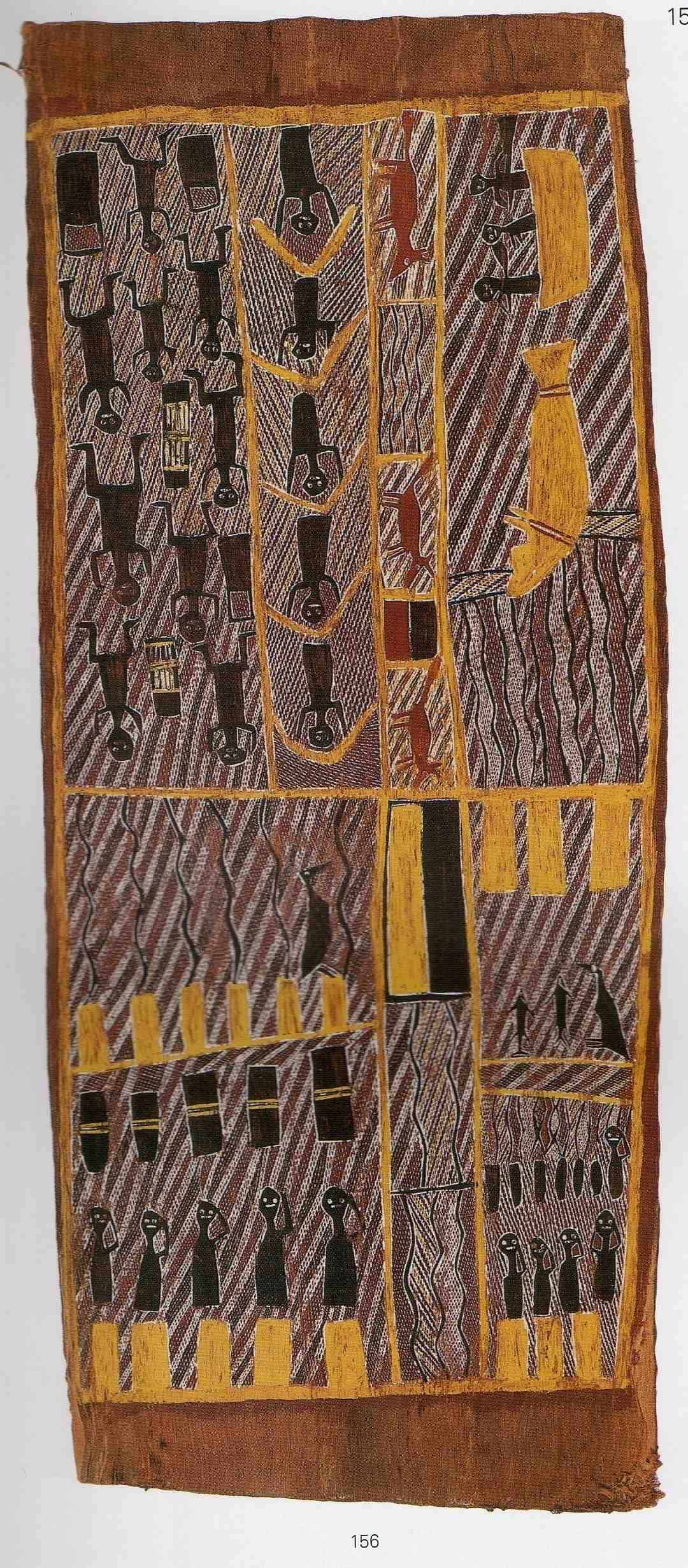

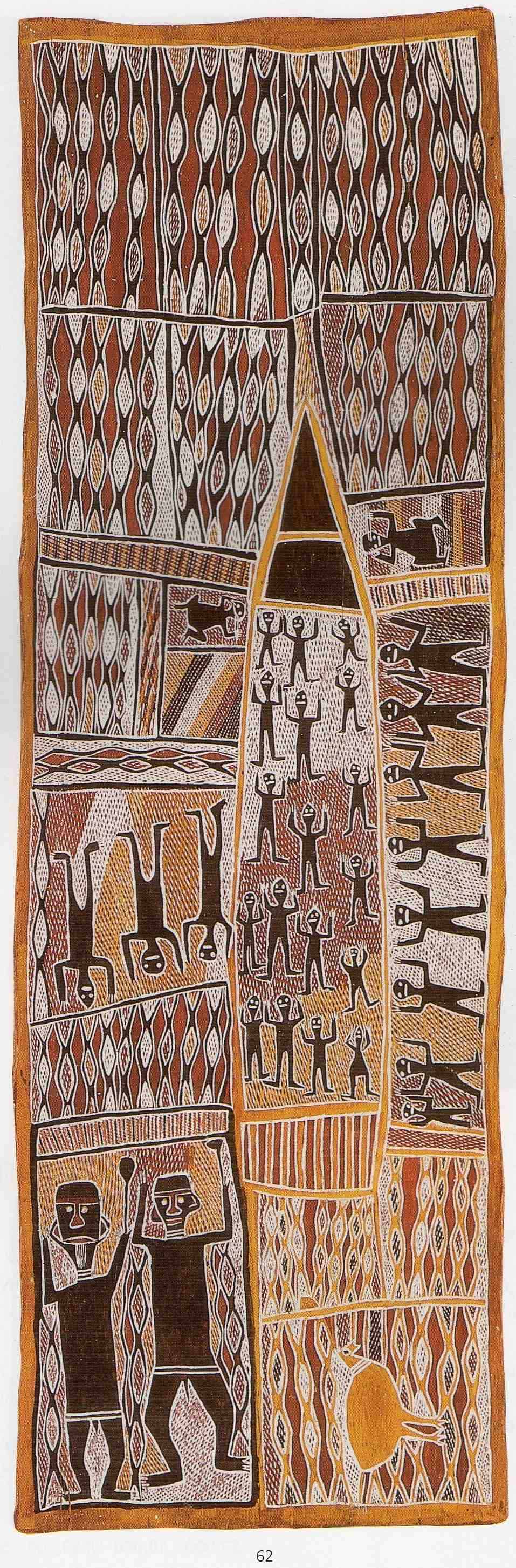

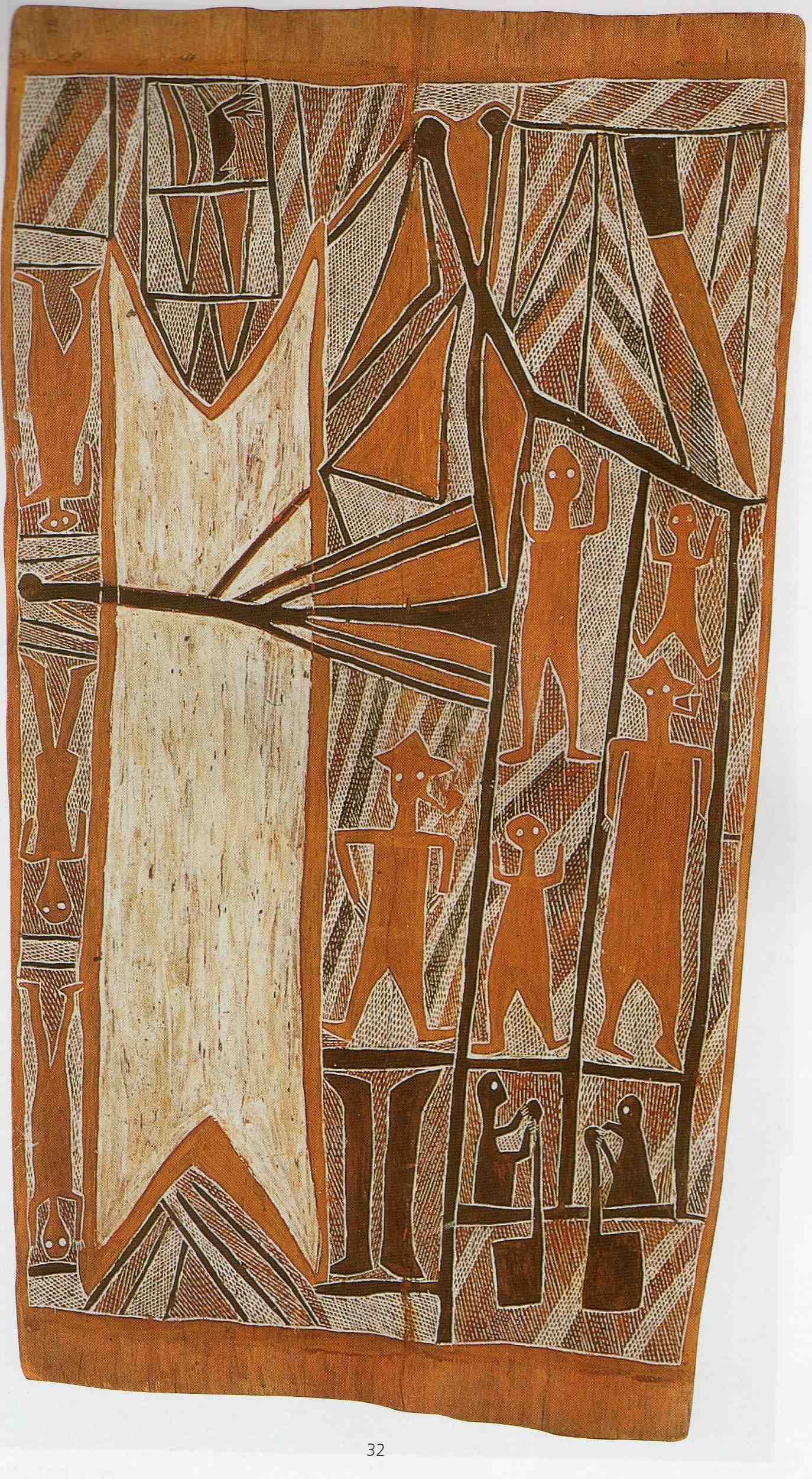

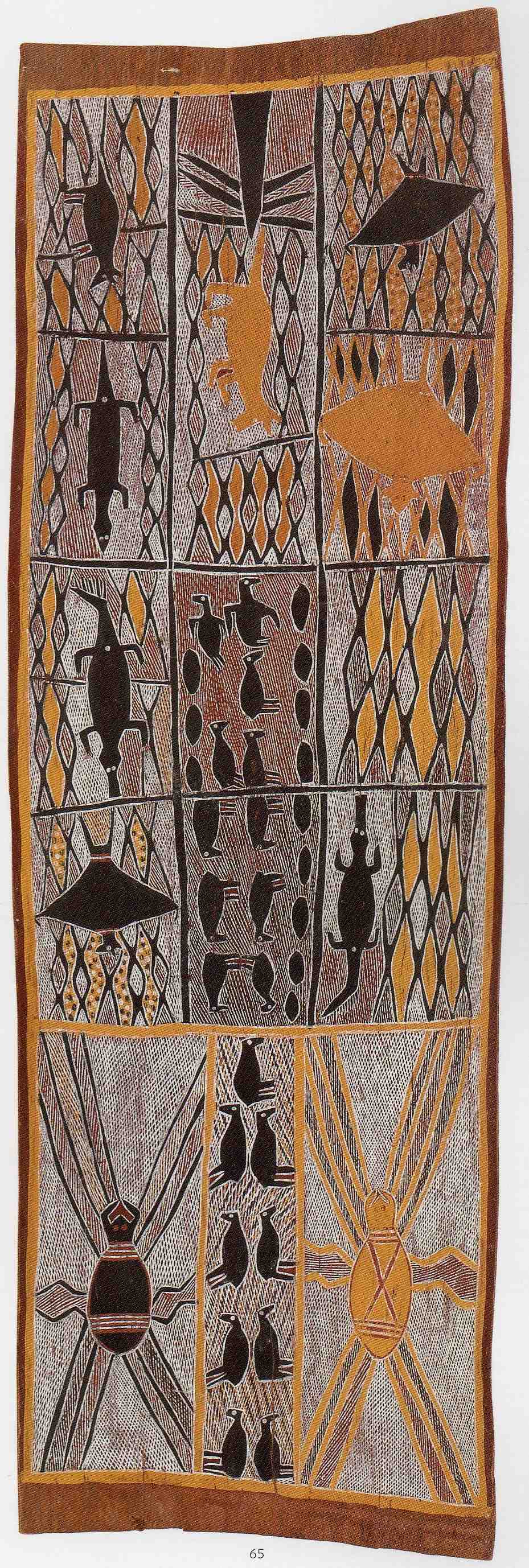

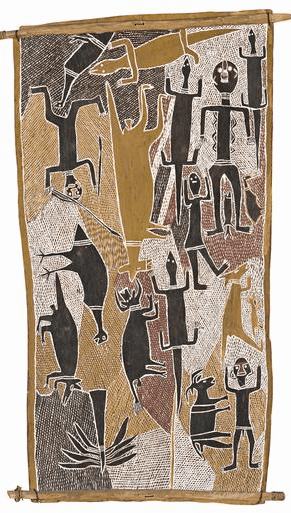

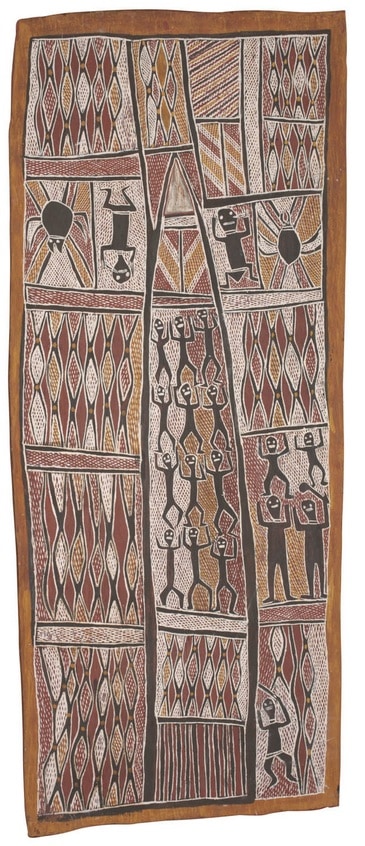

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu was a prolific bark painter and sculpture artist. He was a master of both bark painting and figurative carving. The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their bark painting is by Munggurrawuy Yunipingu. It compares many examples of his work. He painted in a Northeast Arnhem Land style.

If you have a Munggurrawuy Yunipingu bark painting to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your Munggurrawuy Yunipingu painting is worth please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

Style

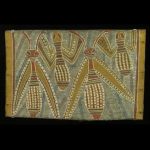

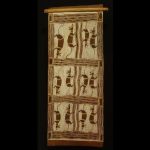

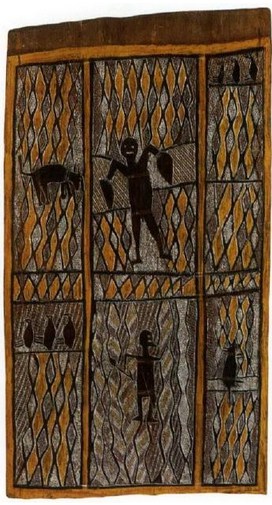

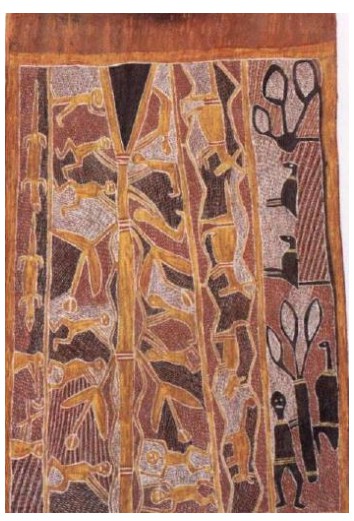

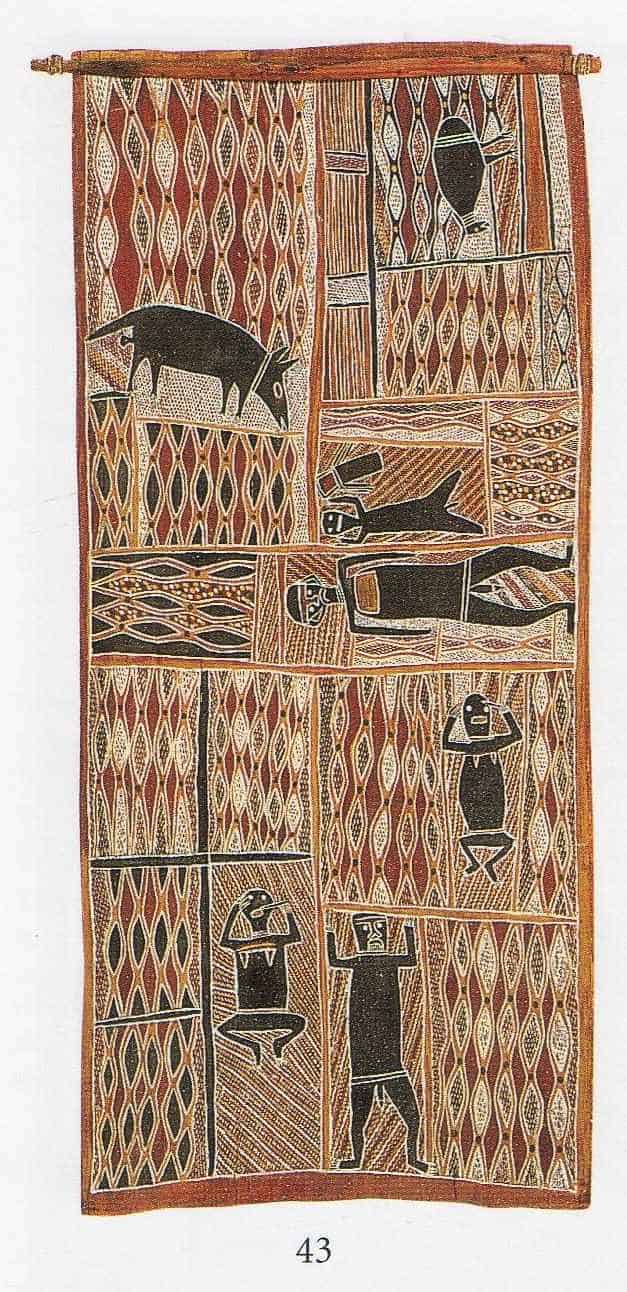

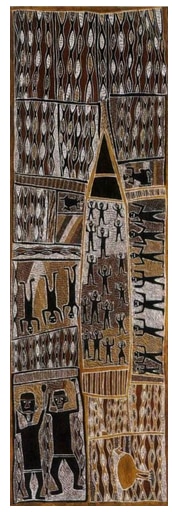

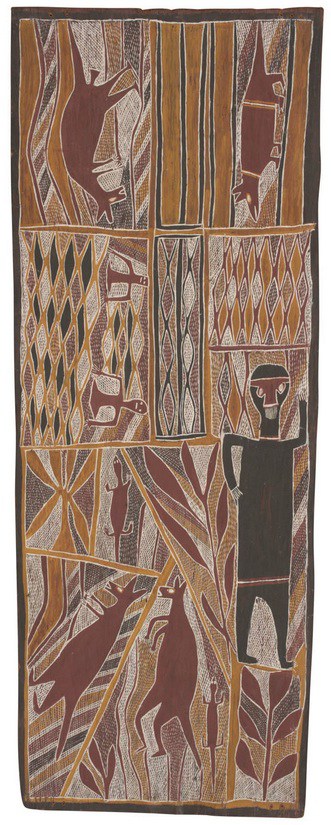

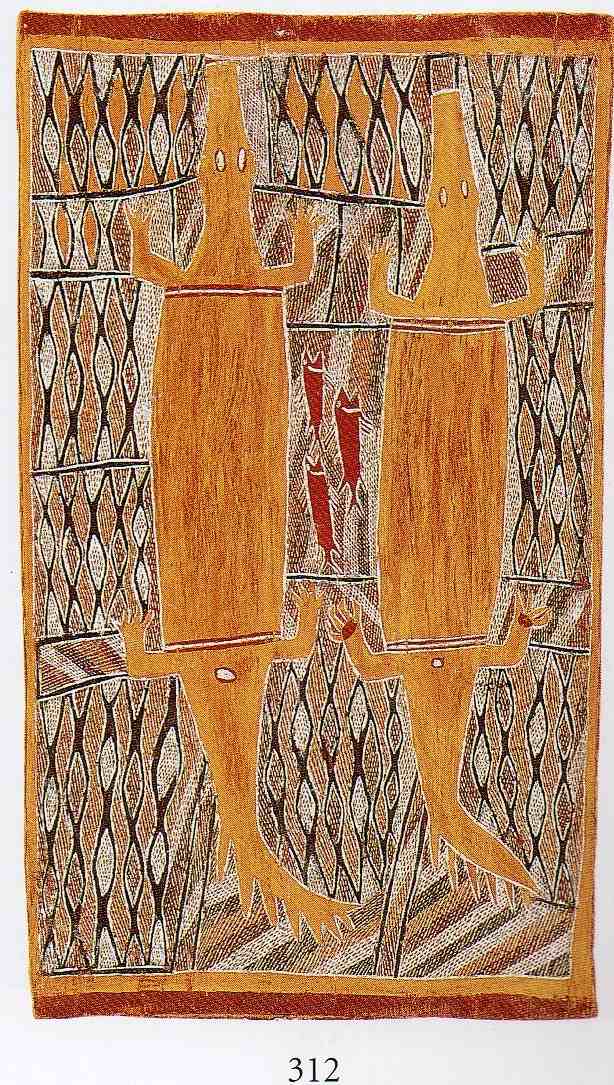

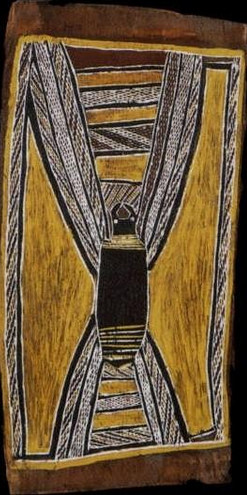

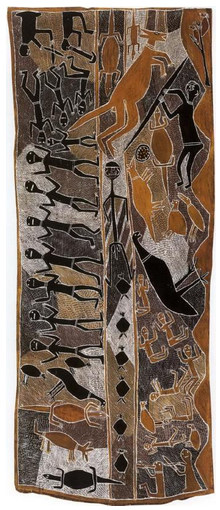

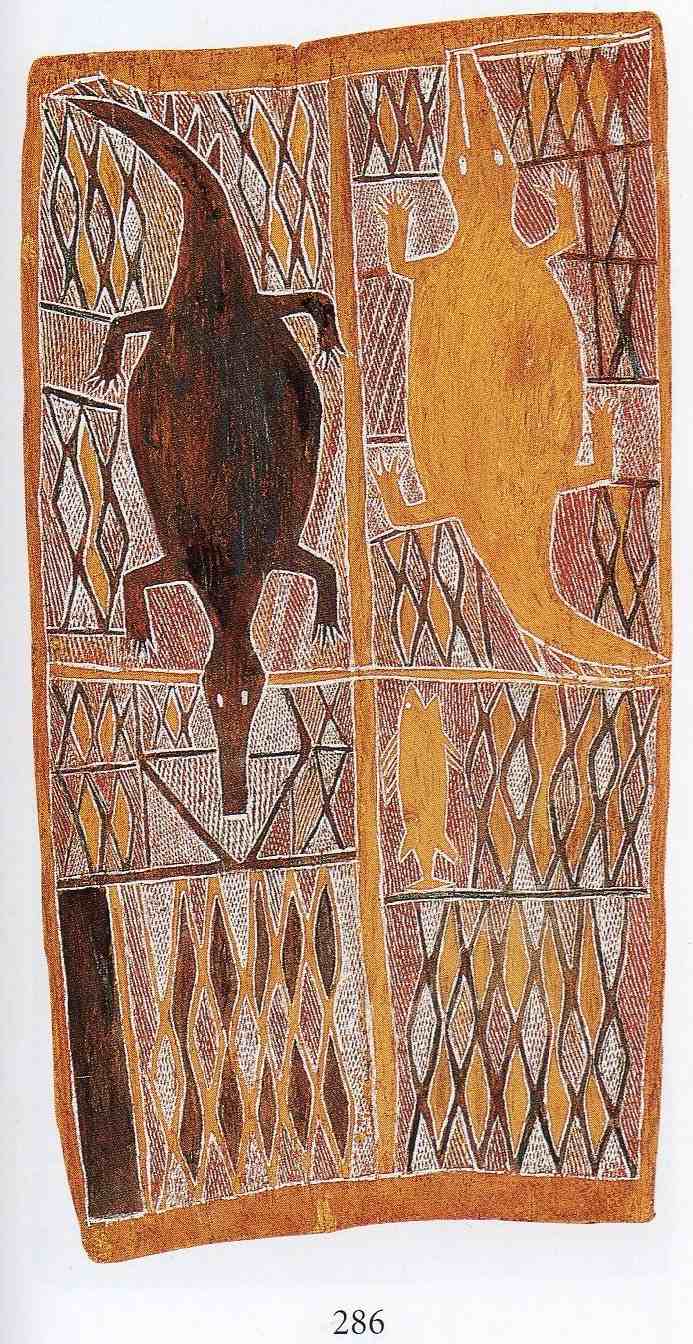

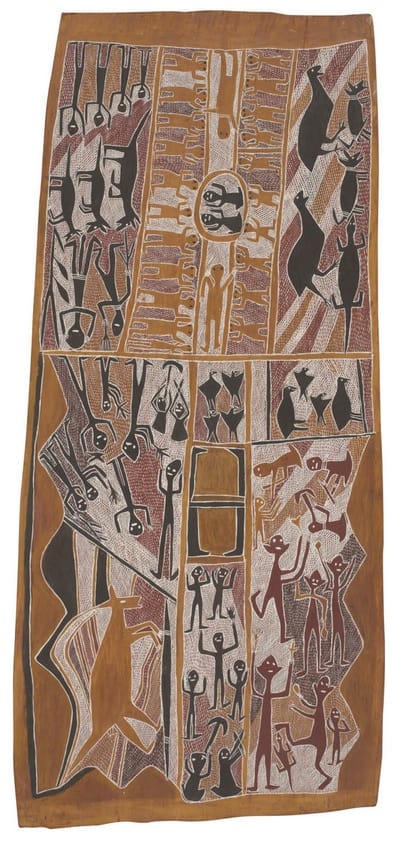

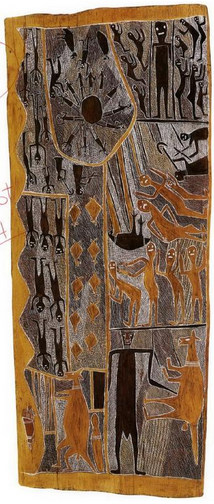

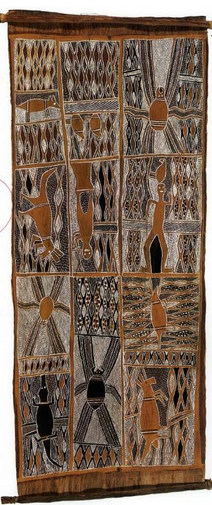

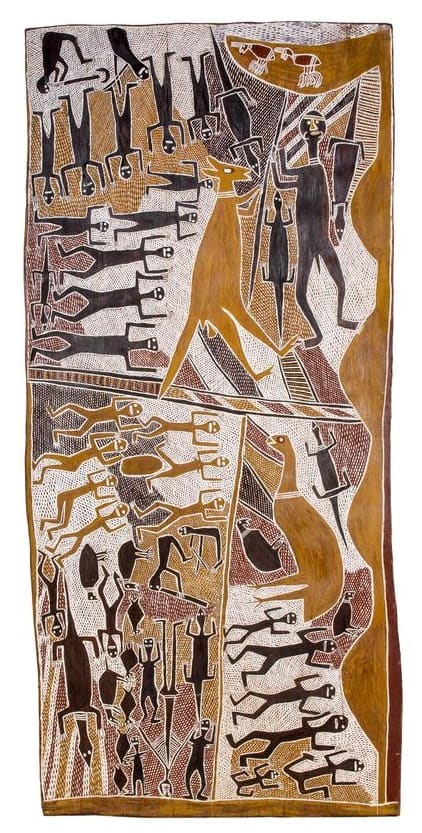

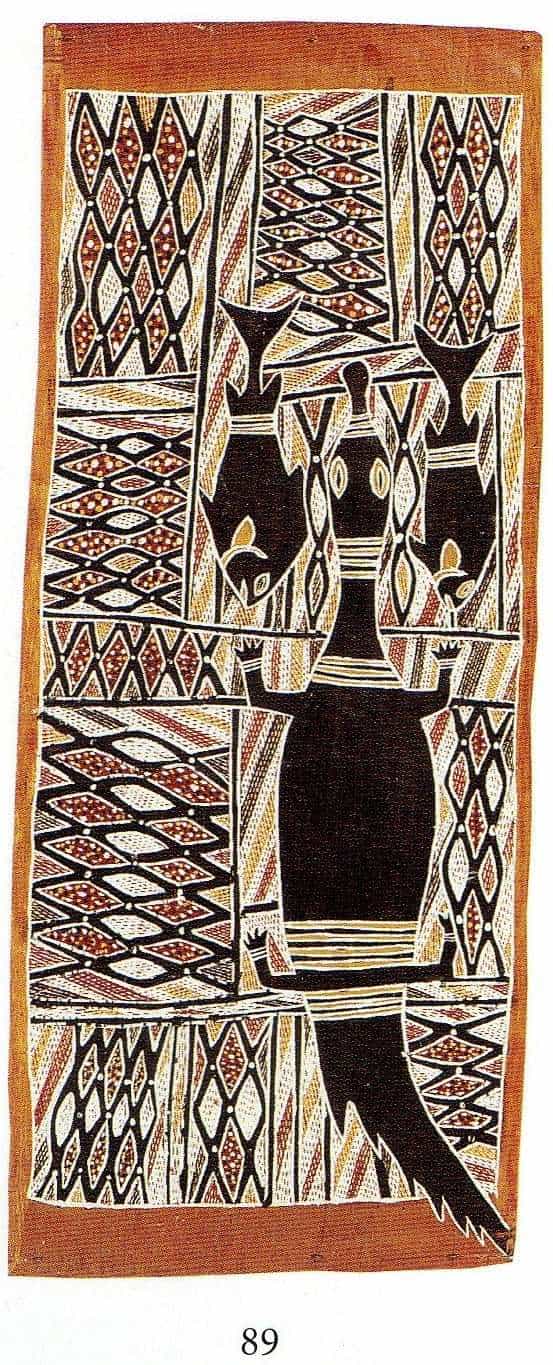

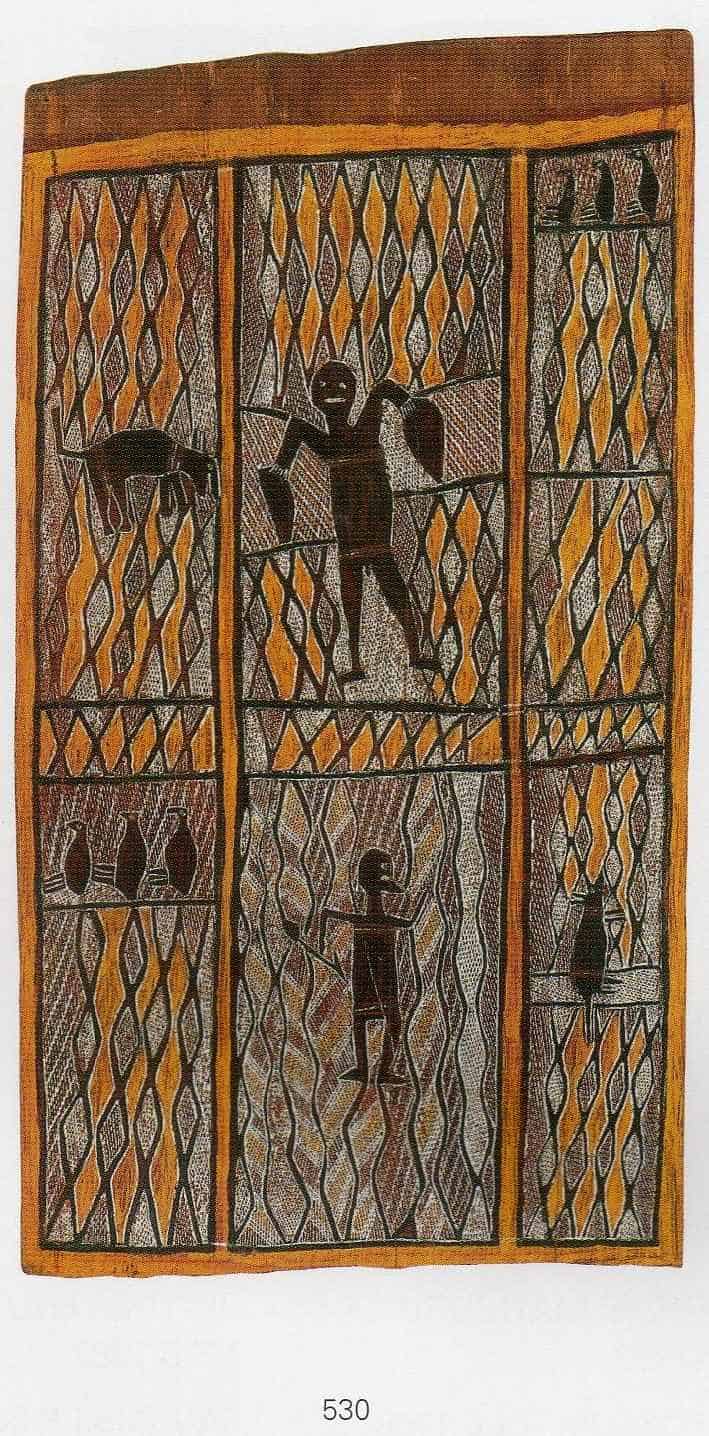

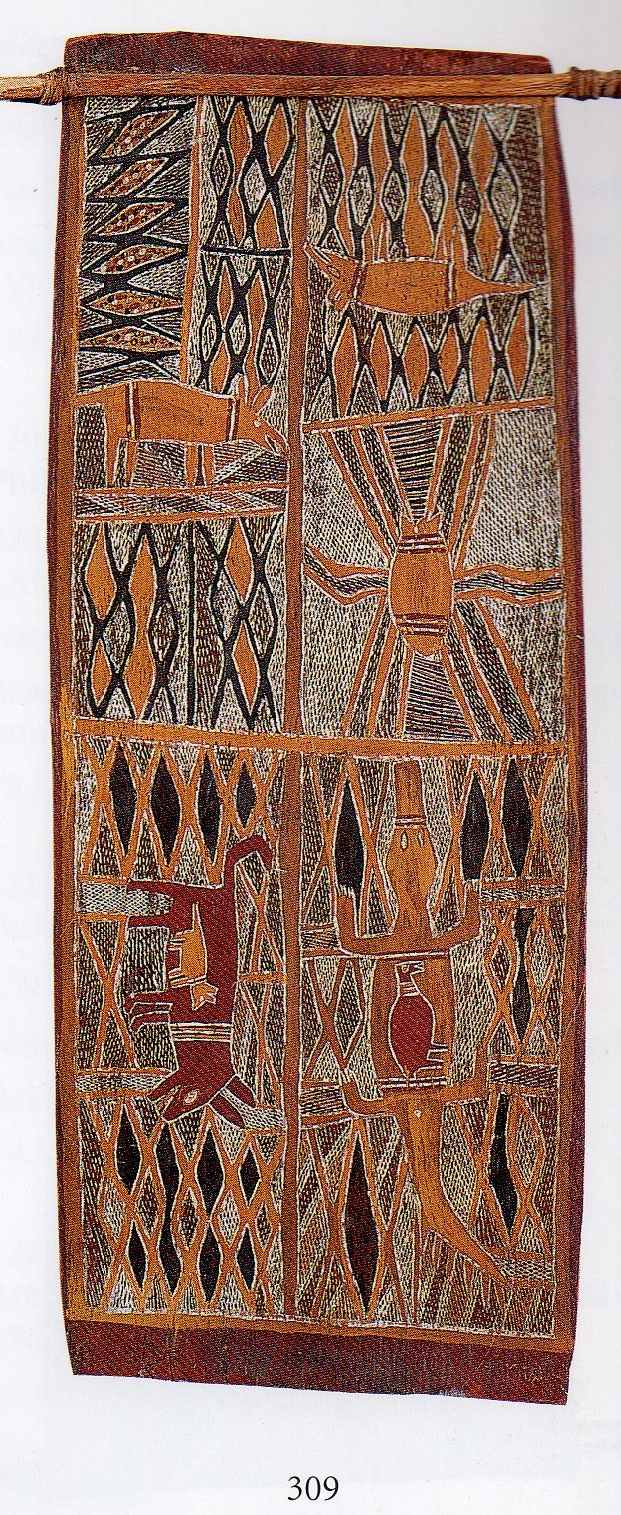

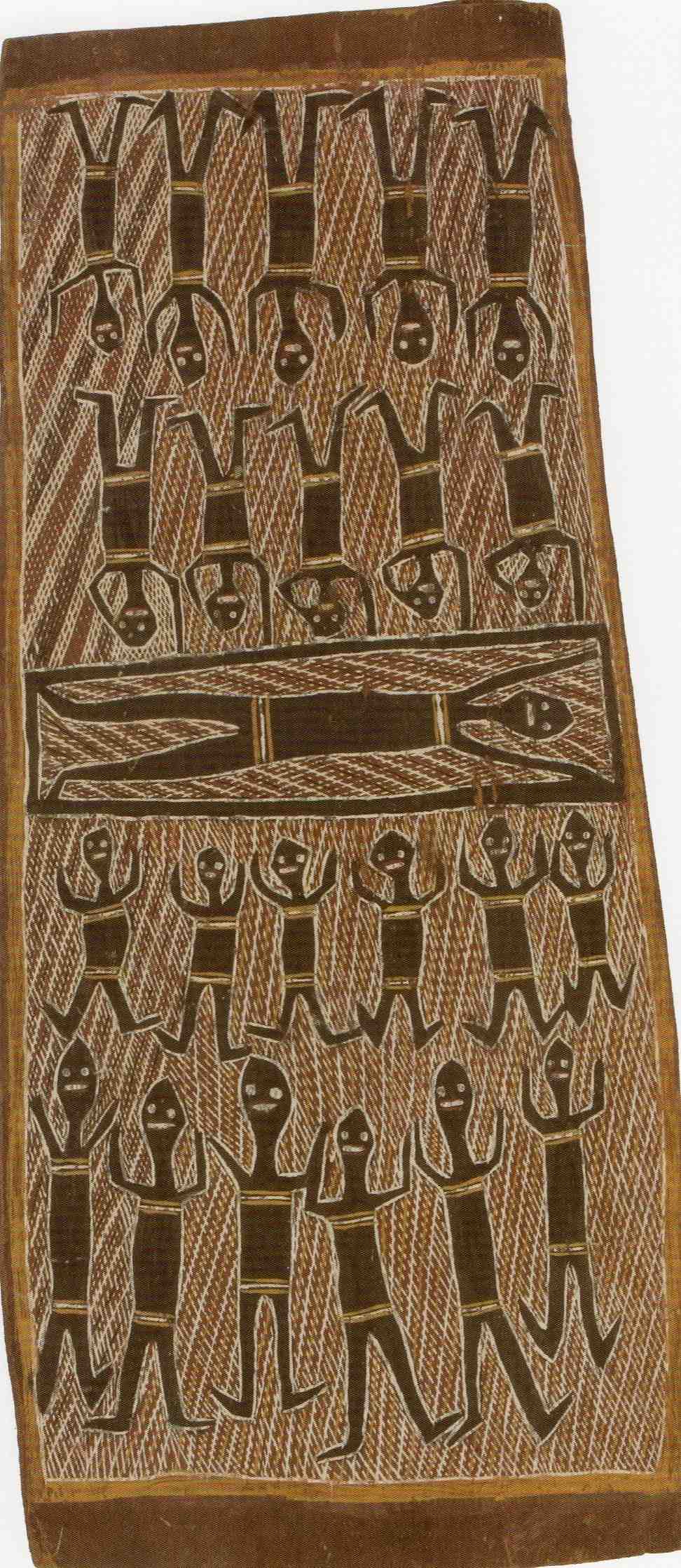

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu early works are very traditional. They consist of geometric schematic clan patterns. It is within these background schematic patterns, that his great skill and control of crosshatching is best demonstrated. He probably along with Mawalan Marika developed an episodic or panel style of bark paintings. These bark paintings consist of panels which each panel represents the same customary story, at different moments. As a result, his allows mythical sequences to unfold across time.

His figures tend to be simplistic with an almost childlike charm to them. This later figurative content expressed mythological themes.He introduced figurative elements because of external demand. He realized other artists received a higher price for figurative work. His best and probably the most sort after works are geometric schematic clan patterns.

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu was also an outstanding sculpture artist. These sculptures are comparatively realistic and covered with painted totemic patterns. According to Roland and Catherine Berndt these sculpture were similar to earlier sacred examples. Sculptures played an important part in the religious life and sacred ceremonies of Yolngu peoples.

The painted patterns on the figures are representations of body painting. Particular designs reflect different ancestors. Figures were originally secret and sacred. The commercial production of these distinctive figures marked a change in artist attitude. They mark when the dominance of individual expression asserted itself over the confinement of traditional cultural values. They are an important step in the development of North-Eastern Arnhem Land art. These sculptures are collectible in their own right.

Biography

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu was born around 1907. He was a senior elder of the Gumatj clan. In the 1960’s and 1970’s he was keeper of the law for the Yirritja moiety. This was an important period of aboriginal history. It is when the Yolngu of North East Arnhem Land gained artistic recognition. Art was also an integral part of a political campaign. This campaign sort recognition of traditional land rights.

Munggurrawuy helped paint the Yirrkala bark petitions in 1963. The bark petitions have become historic Australian documents. They are the first traditional documents prepared by Indigenous Australians recognized by the Australian Parliament. They became the first documentary recognition of Indigenous people in Australian law. Bark paintings acted as a form of land title.

He established an important relationship with Melbourne art dealer Jim Davidson. Jim saw that his work got into major museums both nationally and internationally.

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu’s art has gone on to inspired many other Arnhem Land artists. He also taught his daughter Nyapanyapa Yunupingu to paint. She is a collectible artist in her own right. His works have been in a large number of major exhibitions.

He had twelve wives and numerous children. The most famous of his children was Manawuy who was a talented artist in his own right

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Yirrkala Artworks and Articles

Munggurrawuy Yunipingu Bark Painting images

The following images are not a complete list of the artist’s works but give a very good idea of his style and variety.