Mathaman Marika: Yirrkala Bark Paintings from North East Arnhem Land

Mathaman Marika was a pioneering bark painter from Yirrkala, North East Arnhem Land, whose work in the early 1960s established him as one of the most sought-after Aboriginal artists of his generation. Following the death of his elder brother Mawalan Marika I, Mathaman became leader of the Rirratjingu clan of the Dhuwa moiety, creating masterful depictions of ancestral narratives—richly detailed representations of the creatures, places, and totems central to Yolŋu culture.

This article is designed to help collectors, researchers, and art owners identify whether their bark painting is by Mathaman Marika, drawing on stylistic comparisons and key visual features of his work. If you own a Mathaman Marika bark painting and wish to sell it, or would like to know its value, you are welcome to send a JPEG image and size for assessment—I would be delighted to view it.

Artistic Style and Innovation of Mathaman Marika

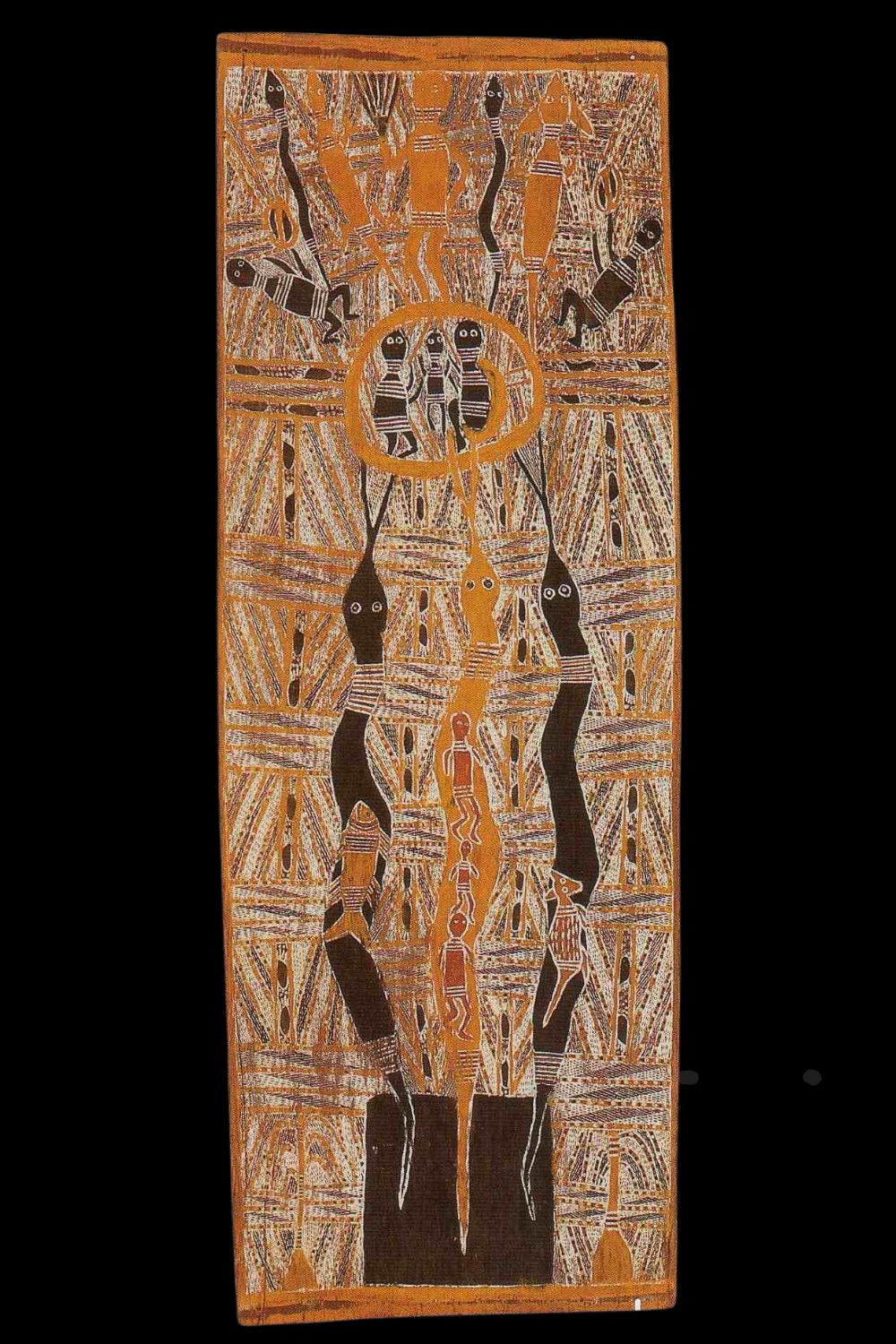

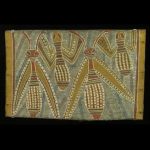

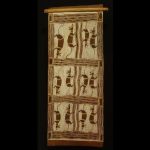

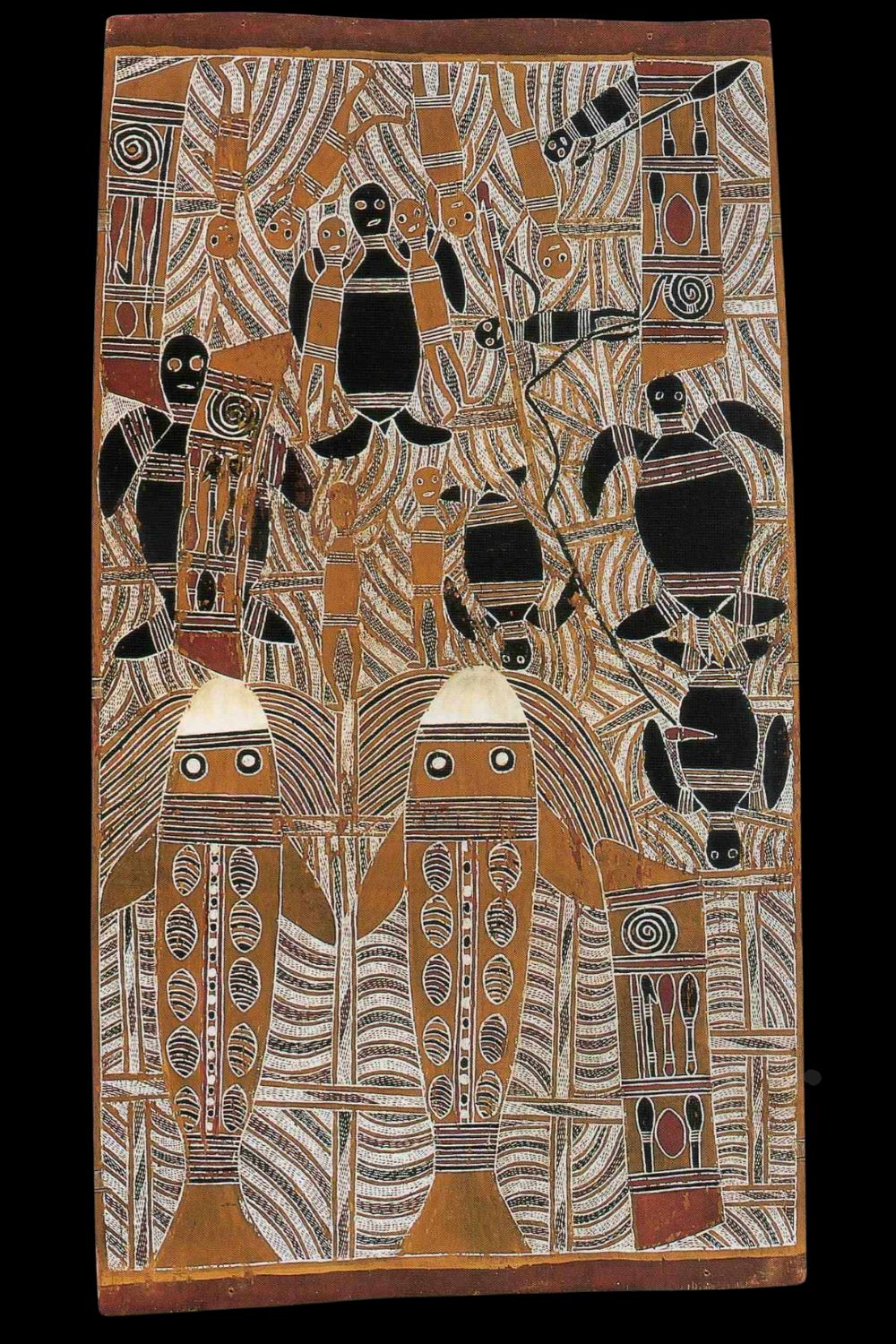

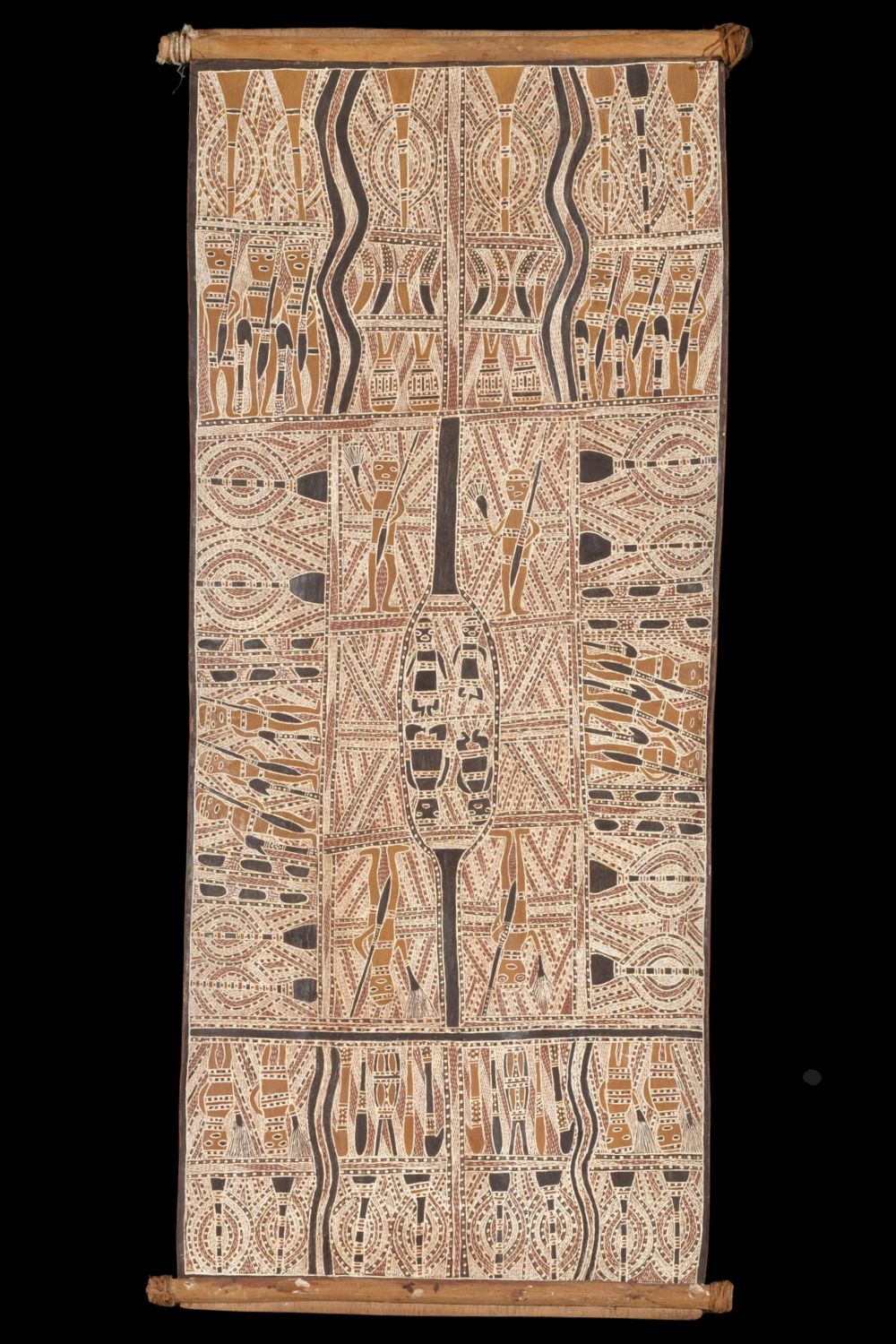

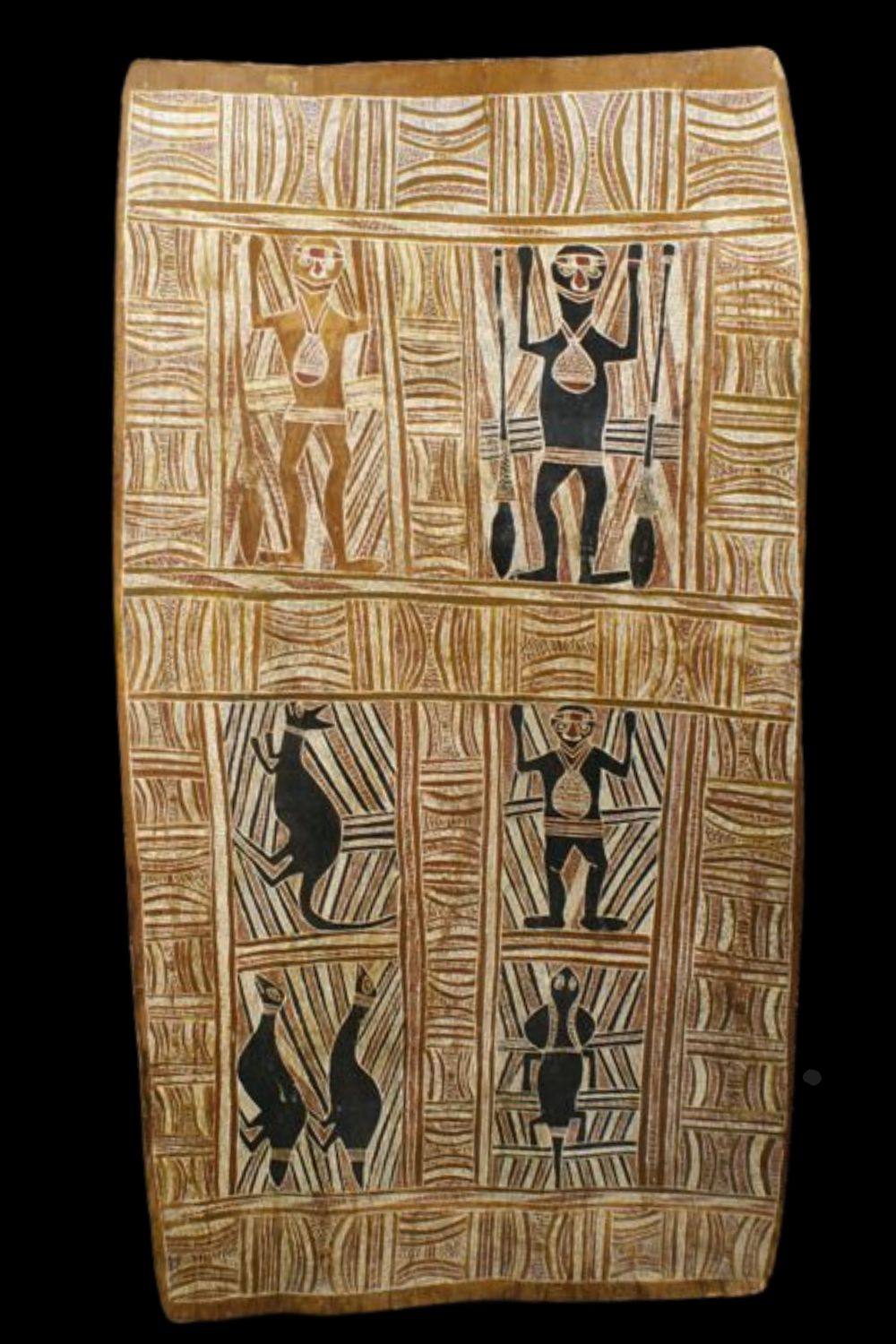

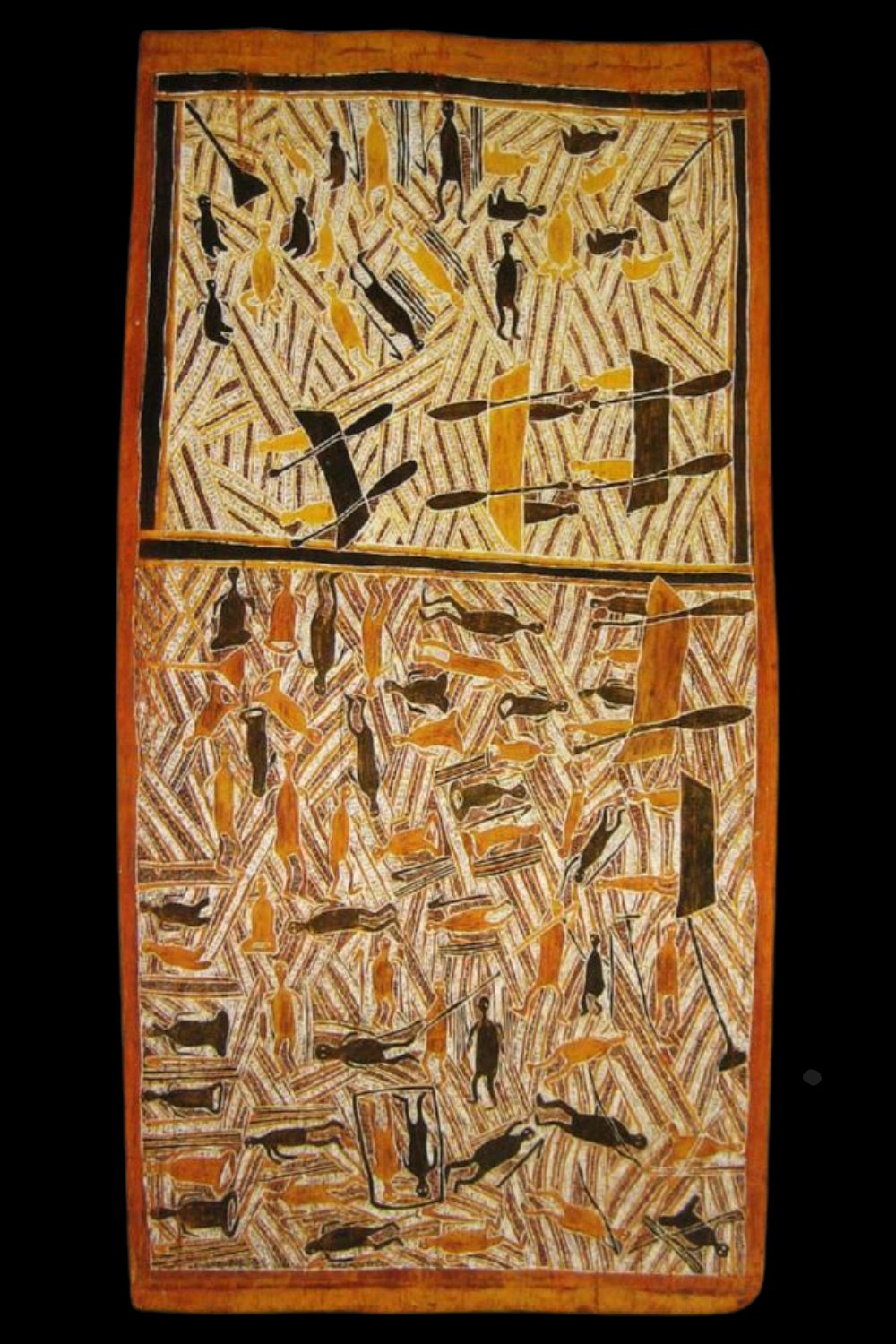

Mathaman Marika’s bark paintings are celebrated for their luminous cross-hatching (rarrk), meticulously applied with a delicacy often described as “spidery” in its fine, deliberate precision. His compositions are characteristically divided into interrelated sections by networks of straight and diagonal lines, creating a visual architecture in which figurative, totemic, and geometric elements coexist in harmonious balance. Totemic animals, ancestral figures, and sacred motifs are rendered in bold silhouette against richly symbolic grounds, producing a striking interplay of abstraction and figuration that conveys a profound spiritual presence.

Technically innovative, Mathaman was the first bark painter from Yirrkala to consistently mix pigments, softening the sharp contrasts of traditional ochre palettes. He favoured warm yellow ochres and muted tones over vivid colour, blending black with yellow to achieve an earthy olive green and substituting stark white with creamier, softened variations. Rejecting European wood glue, he used orchid bulb juice as a natural binder, producing a distinctive matte finish that perfectly complemented his subdued colour harmonies.

While his rarrk is executed with meticulous detail, his figures are often minimal and unembellished, creating a deliberate tension between complexity and simplicity. Mathaman’s bark paintings encompass a rich spectrum of Yolŋu creation narratives, including depictions of the Nhulunbuy stories, the Sugarbag Spirit, the Morning Star Ceremony, and the Wagilag Sisters—ancestral dramas that remain central to the cultural identity of North East Arnhem Land. His ability to unite refined technical mastery with deep ceremonial knowledge places Mathaman Marika among the most significant Aboriginal bark painters of the 20th century.

Biography of Mathaman Marika – Rirratjingu Elder and Master of Arnhem Land Bark Painting

Mathaman Marika was a pioneering bark painter from Yirrkala, North East Arnhem Land, whose work in the early 1960s established him as one of the most sought-after Aboriginal artists of his generation. Following the death of his elder brother Mawalan Marika, Mathaman became leader of the Rirratjingu clan of the Dhuwa moiety, creating masterful depictions of ancestral narratives—richly detailed representations of the creatures, places, and totems central to Yolŋu culture.

This article is designed to help collectors, researchers, and art owners identify whether their bark painting is by Mathaman Marika, drawing on stylistic comparisons and key visual features of his work. If you own a Mathaman Marika bark painting and wish to sell it, or would like to know its value, you are welcome to send a JPEG image and size for assessment—I would be delighted to view it.

Other artists involved in painting the Yirrkala church panels include Birrikitji, Yunapinju and Mithinari.

Mathaman is sometimes spelled Matharman Marika, Mataman Marika, Madaman or Mataman

His works were recently exhibited at the Old Masters Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia.

Rise as an Artist and Cultural Leader

In the decades that followed, Mathaman Marika emerged as one of the leading interpreters of Djangkawu, Wagilag, and Wuyal creation narratives, painting on sheets of eucalyptus bark stripped, cured, and prepared in accordance with tradition. These ancestral stories, central to the Dhuwa moiety, mapped sacred sites, spiritual journeys, and the origins of Rirratjingu society. His work often functioned as both ceremony and declaration—a visual land rights statement rooted in ancient law.

When Mawalan passed away, Mathaman inherited the leadership responsibilities of the Rirratjingu clan. His paintings illuminated the sacred travels of the Djangkawu Sisters, who gave birth to the Rirratjingu people and established the Dreaming tracks connecting clans across North East Arnhem Land.

Recognition and International Collection

The 1950s and 1960s marked a period of growing recognition for Arnhem Land bark painting. Douglas Tuffin, a lay missionary at Yirrkala, introduced the split-stick frame still in use today and began labelling works for authenticity. Mathaman’s paintings quickly found their way into the collections of major figures such as Tony Tuckson (Art Gallery of New South Wales), Dr. Stuart Scougall, Dorothy Bennett, Karel Kupka, Ed Rue, and Louis Allan. His works were acquired by museums and collectors across Australia, Europe, and the United States, elevating him to the forefront of Yirrkala bark painting.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Mathaman witnessed the arrival of the Nabalco mining company on Rirratjingu lands. He organised protest corroborees and instructed younger men in ceremonial and artistic law, ensuring the transmission of sacred knowledge. Mathaman Marika passed away at peace, returning to the Dreaming that had inspired his life’s work.

Today, his paintings remain vital records of Yolŋu cultural heritage—maps of sacred country, embodiments of ancestral law, and masterpieces of North East Arnhem Land Aboriginal art. They are held in major institutional and private collections, testifying to his role as both a cultural leader and a pioneering artist whose vision continues to inspire future generations.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Meaning of Mathaman Marika Bark paintings

Buralku – Spirit Place for the Dead

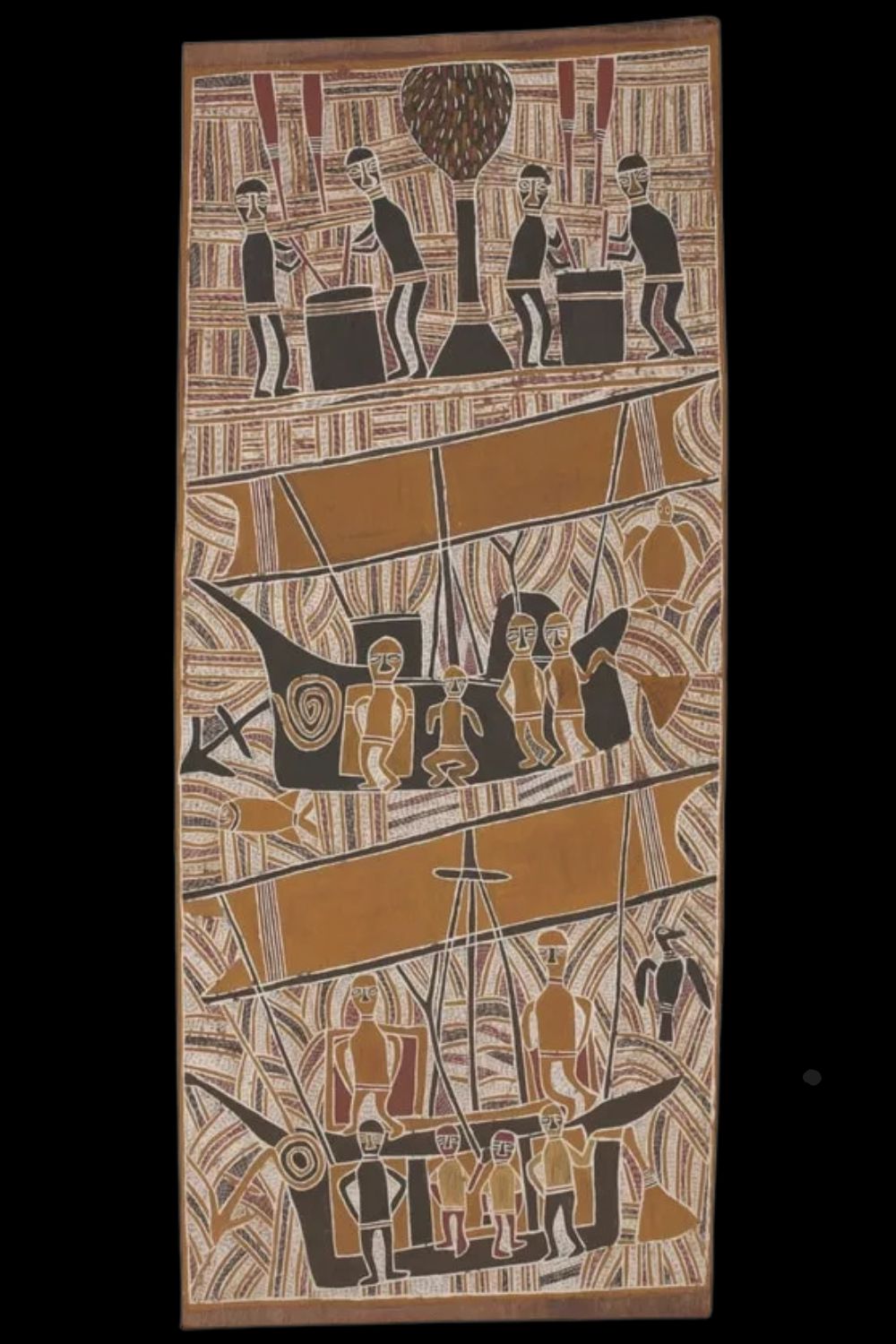

Macassan interactions: Icon of Yolŋu Maritime History in Bark Painting

The Macassan prau (perahu) holds a distinctive place in the cultural and artistic heritage of Arnhem Land, symbolising centuries of maritime exchange between the Yolŋu people and Makassan trepang (sea cucumber) traders from Sulawesi. From the at least the early 18th to the early 20th century, these elegant lateen-rigged vessels brought new technologies, goods, and influences into Yolŋu life, leaving an enduring mark on ceremony and art.

In this Aboriginal bark painting, the Macassans are painted yellow and the Aboriginals painted black. It is more than a record of contact—it represents trade, diplomacy with Yolŋu people depicted cooking and preparing sea cucumbers and Maccassans crews.The depiction is on a background of clan designs, visually anchoring it within the sacred geometry of Yolŋu country.

On the art market, bark paintings featuring the Macassan prau are highly prized for their aesthetic beauty and their role in preserving one of Australia’s most significant maritime histories.

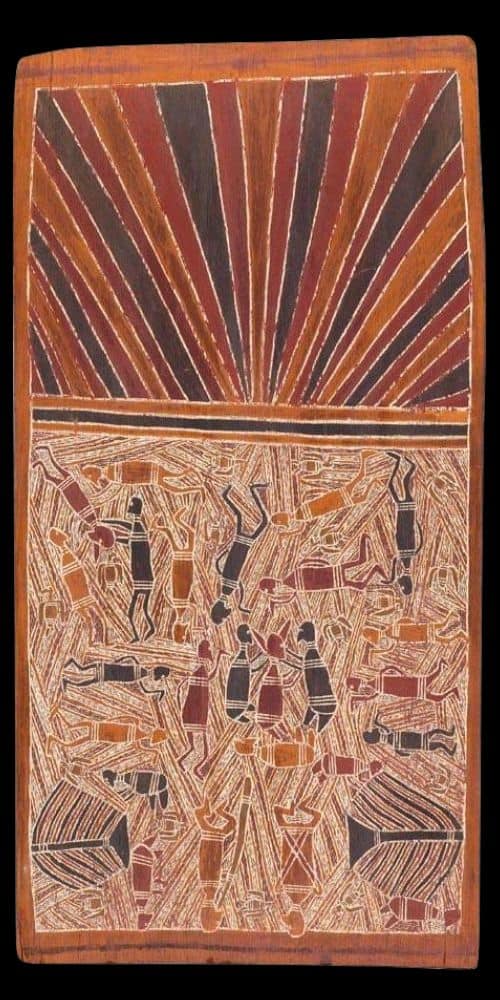

The Wagilag Sisters – Ancestral Law in Arnhem Land Bark Painting

The Wagilag Sisters are among the most important ancestral beings in the cosmology of the Yolŋu people of North East Arnhem Land. Belonging to the Dhuwa moiety, their epic journey forms the foundation of ceremonial law and inter-clan relationships, and remains a central subject in Aboriginal bark painting.

According to Yolŋu tradition, the Wagilag Sisters travelled across country with their children, naming places, creating sacred sites, and instituting the laws, ceremonies, and kinship structures that continue to guide Yolŋu society. Their journey is most dramatically remembered for the confrontation with the great Rainbow Serpent (Ngalyod). Seeking shelter in a sacred waterhole, the sisters inadvertently transgressed local law, angering Ngalyod, who rose from the depths, encircling and eventually swallowing them. This act of retribution sealed the sacred status of the site and became a cautionary law story passed down through generations.

In Yirrkala bark painting, the Wagilag Sisters are often depicted alongside the serpent, their forms rendered in natural ochres with luminous rarrk (crosshatching) and geometric clan designs. Each composition functions both as an artwork and a ceremonial document, embedding legal, moral, and territorial meaning within its design.

Collectors prize these works for their aesthetic beauty, historical resonance, and their role in preserving one of Arnhem Land’s most profound narratives—a story of creation, law, and the enduring balance between people, ancestors, and land.