Animals in Aboriginal Art – A Teacher’s Guide for the Classroom

A teaching resource

Welcome! This page is designed to support primary school teachers with background knowledge, resources, and engaging activities to help you confidently teach about animals in Aboriginal art. You’ll find information about how animals are used in traditional Aboriginal stories, ideas for the classroom, and art templates inspired by real Aboriginal art styles. There’s even a PowerPoint to help get you started.

Why Are Animals So Important in Aboriginal Art?

Aboriginal people have lived across Australia for over 50,000 years, developing a deep understanding of the land, the seasons, and the animals that share their Country. Many Aboriginal groups were traditionally hunters and gatherers, with an intimate knowledge of animal tracks, behaviours, and habitats.

But in Aboriginal art, animals are much more than just food or wildlife—they are part of a bigger spiritual world.

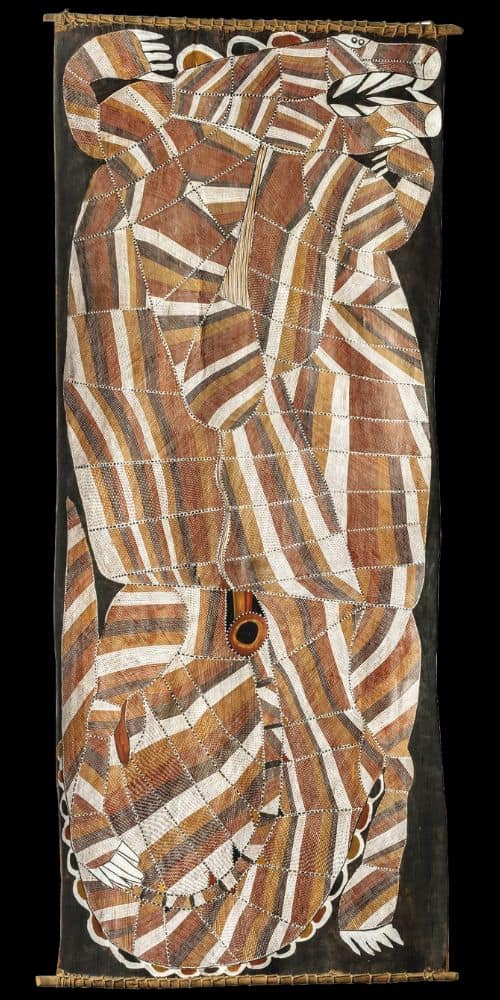

Echidna by

Animals and the Dreamtime

Many animals in Aboriginal art are part of Dreamtime stories, also called Songlines. These are ancient stories that explain how the land, rivers, animals, and people were created. They are passed down through generations by storytelling, song, dance, and ceremonial art.

When you see an animal in Aboriginal art, it’s not just a drawing of a kangaroo, emu, or goanna—it represents a character in a sacred story, often with rules, lessons, and spiritual meaning. Different Aboriginal groups have different stories, and so they paint different animals depending on their Country and clan.

A Long History of Animal Art

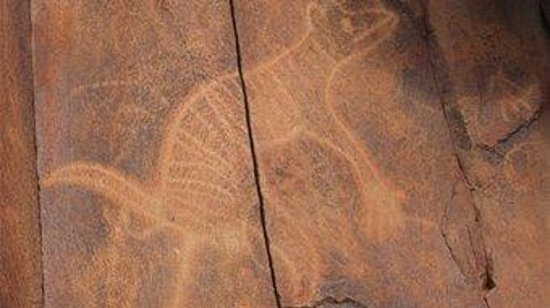

Did you know that some of the oldest artworks in the world are Aboriginal rock paintings of animals?

- Aboriginal rock art goes back tens of thousands of years.

- Some paintings show extinct animals—like the Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger)—which disappeared from parts of Australia over 11,000 years ago.

- A painting of a Thylacine was found in the Pilbara region of Western Australia—proving how long animals have been part of Aboriginal storytelling and art.

These ancient artworks show us that animals have always had a special place in Aboriginal culture and belief systems.

A famous example of this is the Thylacine or Tasmanian Tiger. A Tasmanian tiger appears in rock art in the Pilbara in Northern Australia. It went extinct in this area eleven thousand years ago at the end of the last ice age.

Right: Animals in Arnhemland Rock Art

Different Styles of Animal Art Across Australia

There isn’t just one style of Aboriginal art. Australia is a big country, and Aboriginal people from different regions have different ways of telling their stories.

Let’s look at two major styles:

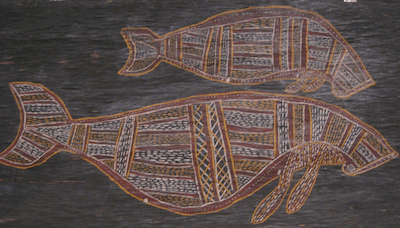

1. X-Ray Art from Arnhem Land

In Western Arnhem Land, artists often draw animals using a style called X-ray art. This means the painting shows both the outside and inside of the animal—bones, organs, and all!

Here are some key features of X-ray animal art:

- The background is a single colour (often red, yellow, or brown).

- The animal’s outline is filled with white.

- Inside the animal, you’ll see patterns made with red, yellow, black, and white.

- Artists use cross-hatching, parallel lines, and dotting to show detail.

🖍 Classroom tip: This is a wonderful style for students to try, because it teaches them to look closely at shapes and patterns, and it respects the traditions of Aboriginal art.

2. Dot Style and Animal Tracks from Central Australia

In Central Australia, animals are sometimes shown in a more symbolic way. Rather than painting the whole animal, artists often use footprints, track marks, or abstract shapes to represent animals in their stories.

This means that a painting might not look like an animal at first—but to Aboriginal people who know the story, the meaning is clear.

🖼 Teacher tip: These paintings are about connection to Country, and they’re often created during ceremonies. While this style is beautiful, it’s harder for students to understand without deeper cultural context. That’s why it’s often better to focus on X-ray styles or narrative animal images for primary school art activities.

How to Teach Animals in Aboriginal Art in the Classroom

To help bring this topic to life, I’ve included:

- A PowerPoint slideshow explaining the role of animals in Aboriginal art and culture.

- Printable art templates for students to create their own “X-ray style” animal artworks.

- Easy-to-follow instructions using traditional techniques like monochrome backgrounds, white outlines, and patterned infill.

These resources are designed to be respectful, age-appropriate, and engaging for primary students. They also help students explore visual storytelling, pattern, and cultural diversity in Australian history.

Final Thought: Animals Are More Than Just Animals

In Aboriginal art, animals are not just painted because they look interesting—they are part of a living cultural tradition. They belong to stories that are sacred and are painted with deep meaning. When teaching students about animals in Aboriginal art, it’s important to share that these are spiritual symbols, not just decorations.

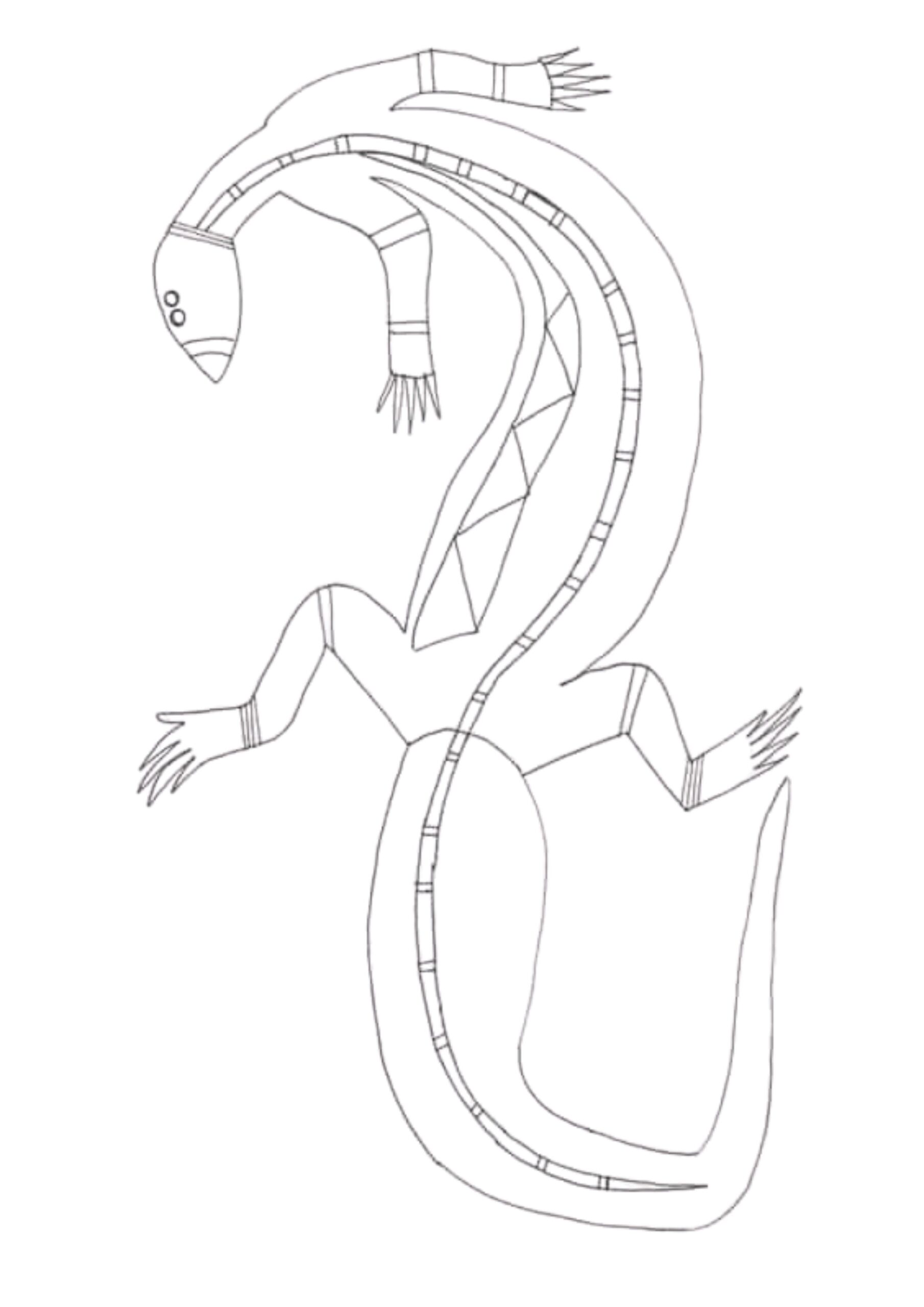

Aboriginal Animal Art Templates

I have attached some Aboriginal Art Animal templates based on art by aboriginal artists which you are welcome to use.

Students should be encouraged to fill in areas with cross-hatching or parallel lines rather than solid blocks of color.

The templates are free to use and original designs but draw heavily on artworks by Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek and Dick Murra Murra.

Aboriginal Art Animal Stories

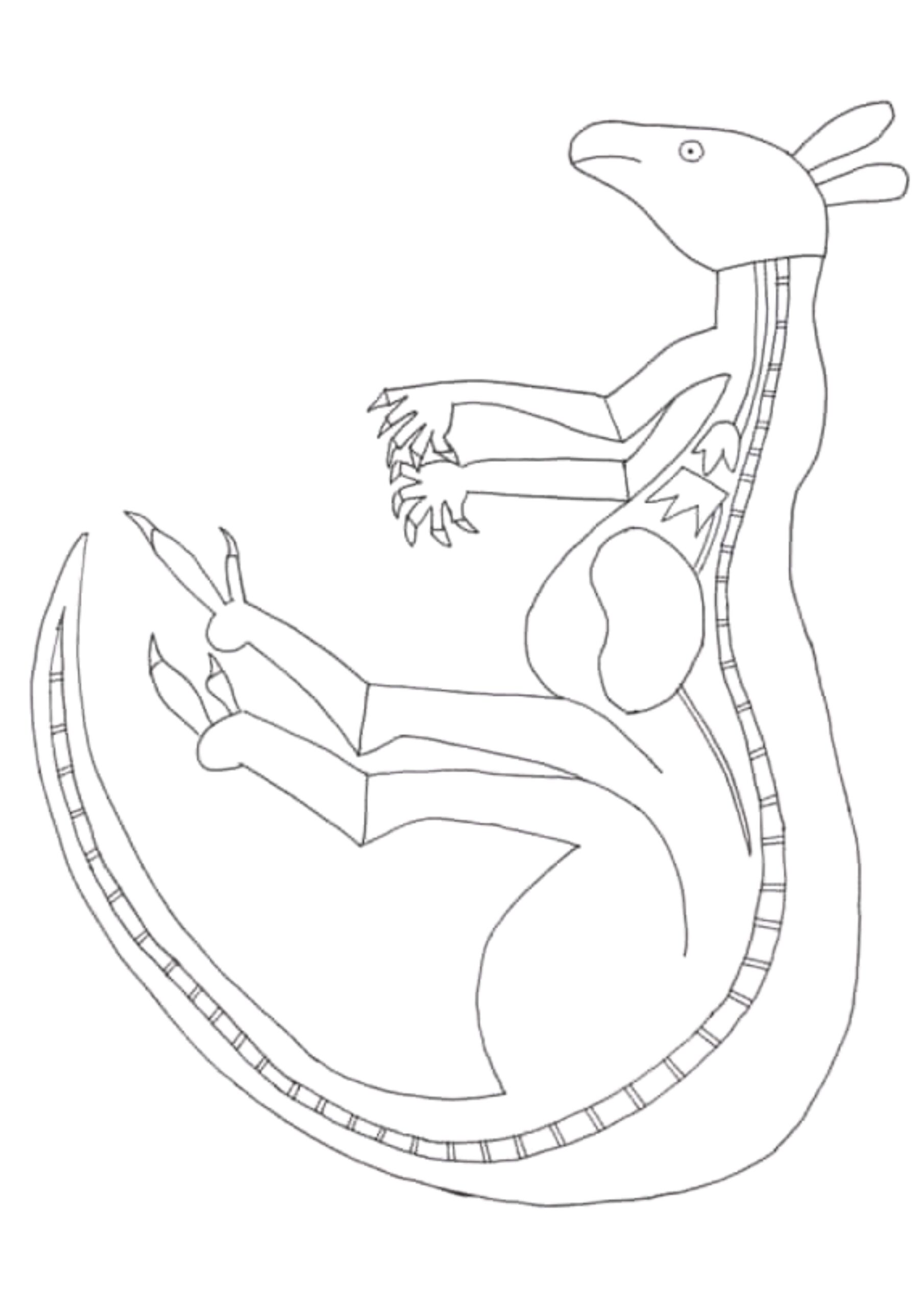

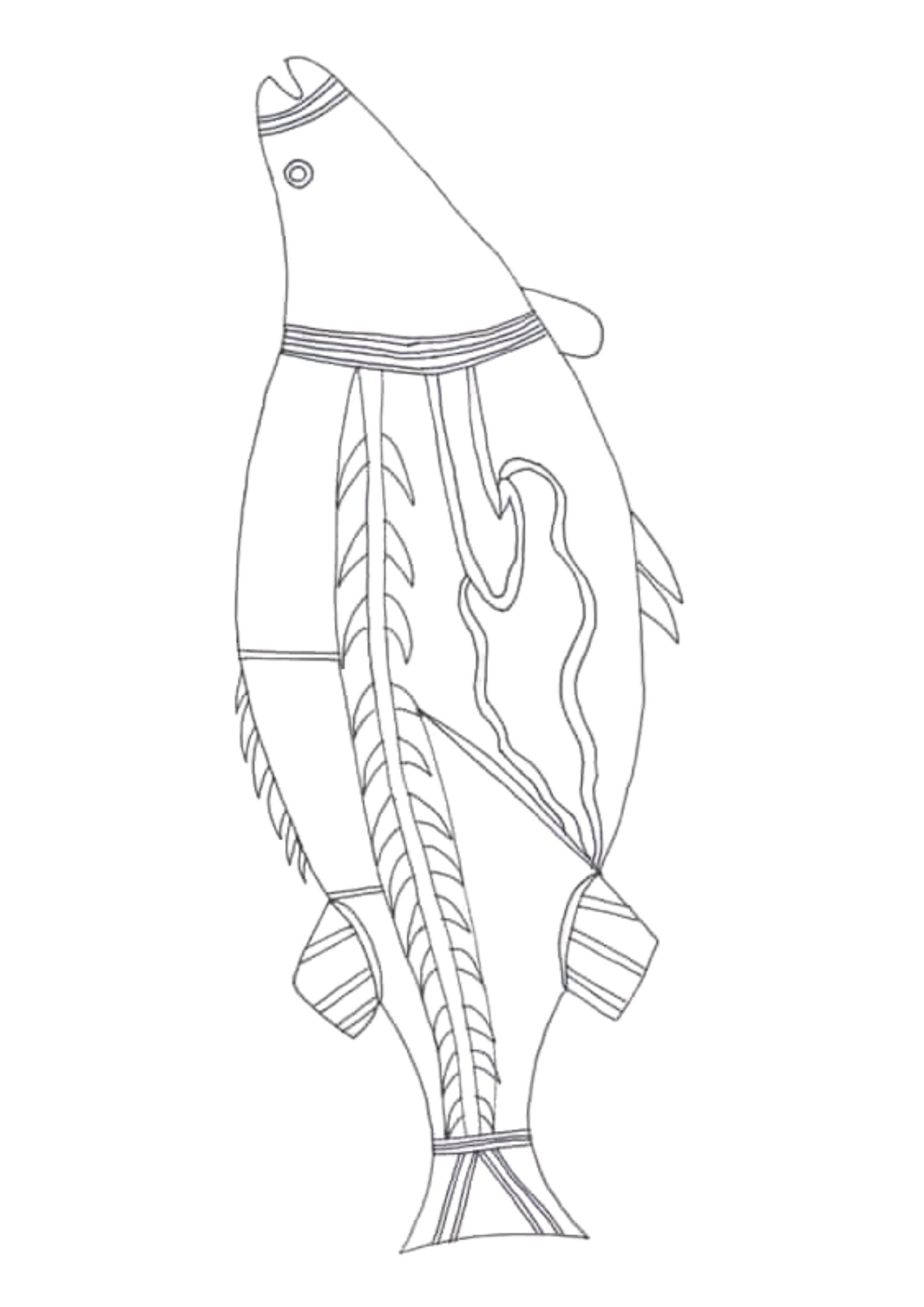

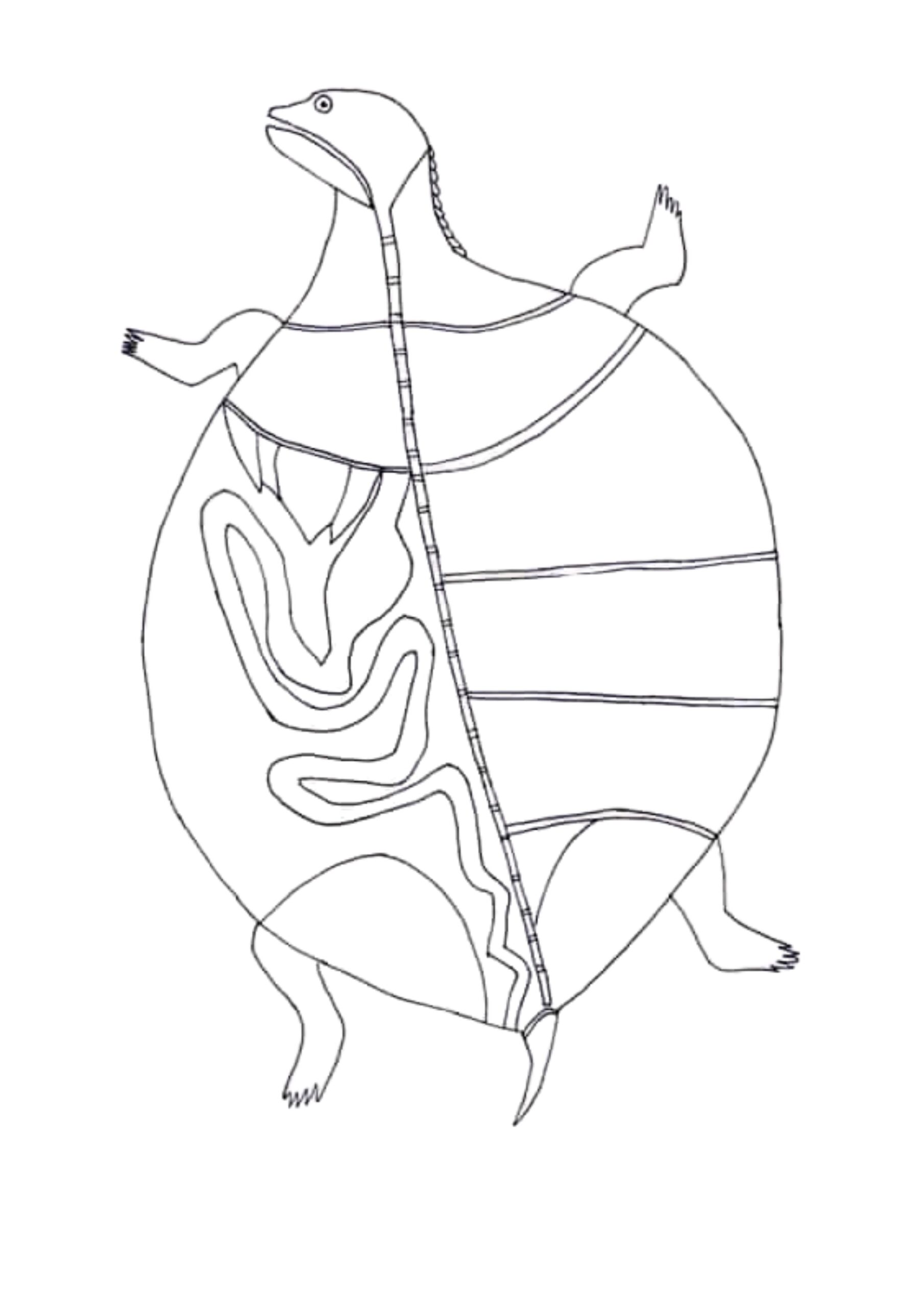

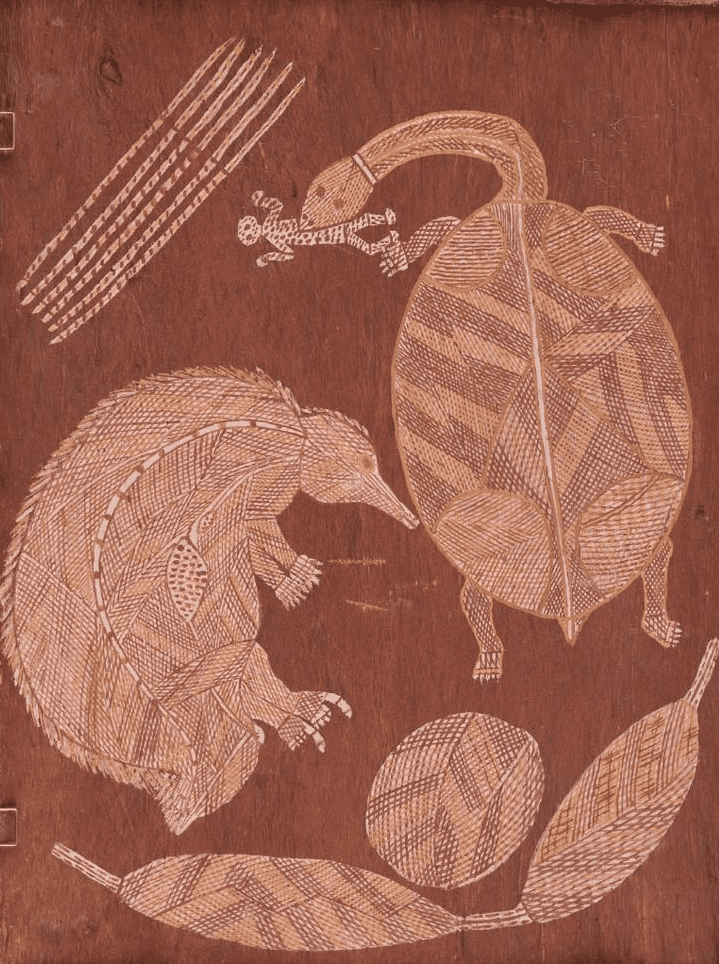

The Echidna and the Turtle.

The Echidna and long neck turtle are important species that features in the Yabbadurruwa ceremony.

There is an important creation story of the battle between two powerful beings Ngarrbek and Ngalmangiyi. Ngarrbek had a young baby eaten by Ngalmangiyi. This lead to a legendary battle between the two powerful ancestors.

Ngalmangiyi had many spears and threw so many at Ngarrbek they covered his entire body. These spears later transformed into the spines and turned Ngarrbek into an echidna.

Ngarrbek however possed a magic grindstone which he smashed onto the body of Ngalmangiyi. The grindstone transformed into a hard shell and Ngalmangiyi turned into a Northern Snake-necked Turtle.

At the site where this epic battle occurred, there is still a thicket of bamboo grass used for making spears.

This legendary battle is still acknowledged through ceremony. Kuninjku performs two major regional ceremonies, the Kunabibbi and Yabbadurruwa. The ceremony celebrates the major creation journey of creator beings. These creator beings travelled first north, and then returned south, through their country. Kunabibbi belongs to the Duwa moiety social grouping. Yabbadurruwa belongs to the Yirridjdja moiety.

The two ceremonies are a pair, whereby the different social groups have reciprocal roles to play. One group aligns with Ngalmangiyi (Duwa Moiety) and the other with Ngarrbek (Yirridjdja Moiety). The ceremonies maintain the cycle of the seasons, and, in particular, the general fertility brought to the world by the coming of the wet season.

The long neck turtle and Echidna are often depicted with interior decoration to emphasise their important ceremonial role.

Turtle and Echidna Story.

Notice at top left is the spears and at the bottom the grinding stone.

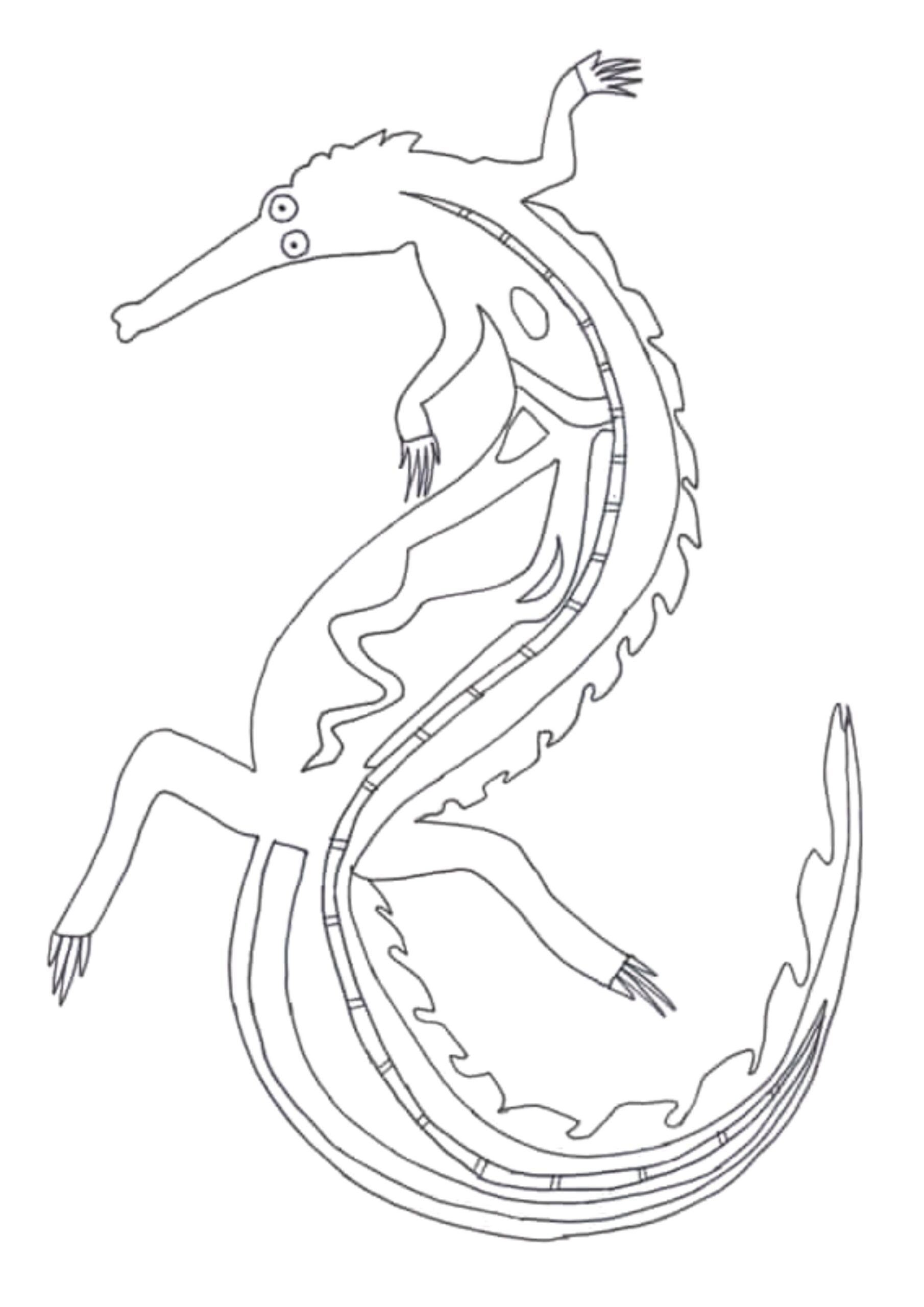

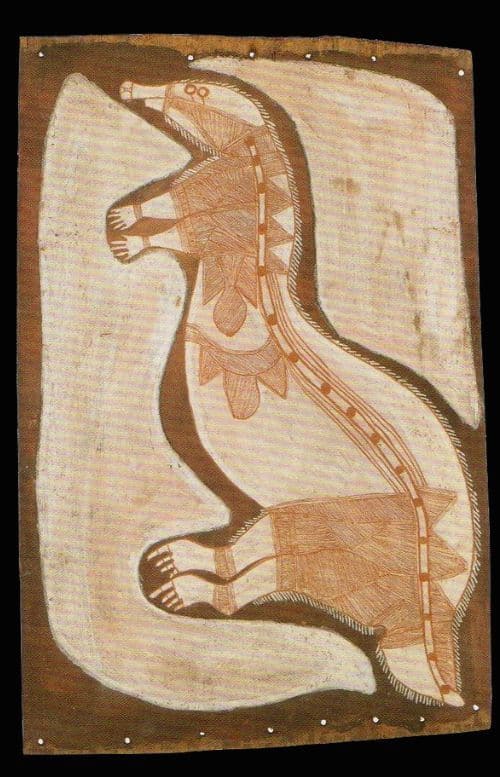

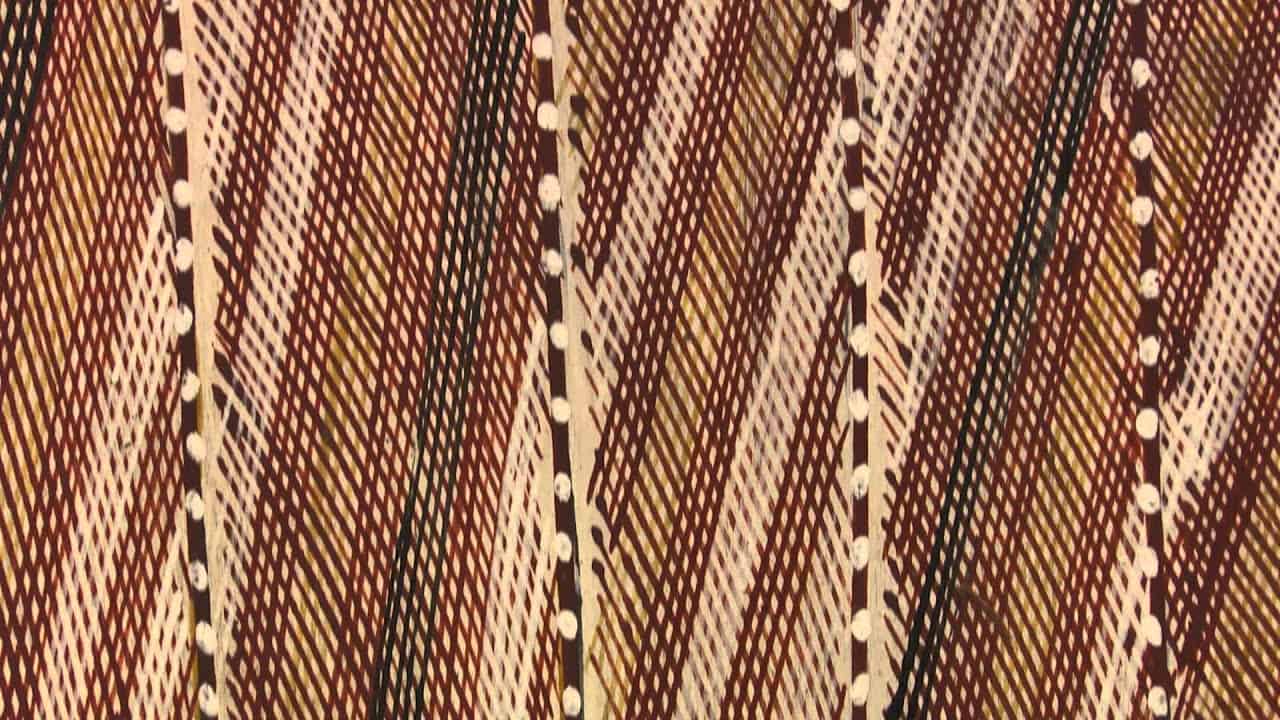

Namanjwarre The Crocodile

Namanjwarre, the saltwater crocodile, Corcodylus porosus. Namanjwarre is a Yiridja moiety totem.

The estuarine crocodile or Namanjwarre is the protector of the sacred objects of the Mardayin ceremony. The Mardayin ceremony is an important rite of passage for Kuninjku language speakers of Western Arnhem Land. Namanjwarre would devour anyone who transgressed from the correct ceremonial protocol.

The upper Liverpool River and Maragalidban Creek areas had lots of these crocodiles. Crocodiles are rarely killed for food but their eggs are sought after during the wet season when the females are nesting. A major crocodile sacred site exists near the outstation of Kurrindin, in the Liverpool River District.

The treatment of the infill of Namanjwarre is the same used on Mardayin ceremonial objects. Mardayin objects decorated with the same bright patterns of crosshatching and dotted lines. Mardayin objects are secret and sacred. The use of the same design within the crocodile, thus, shows the interconnection of the crocodile and the Mardayin ceremony.

Namanjwarre is an important totem and is danced in the sacred and secret ritual of the Mardayin ceremony.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

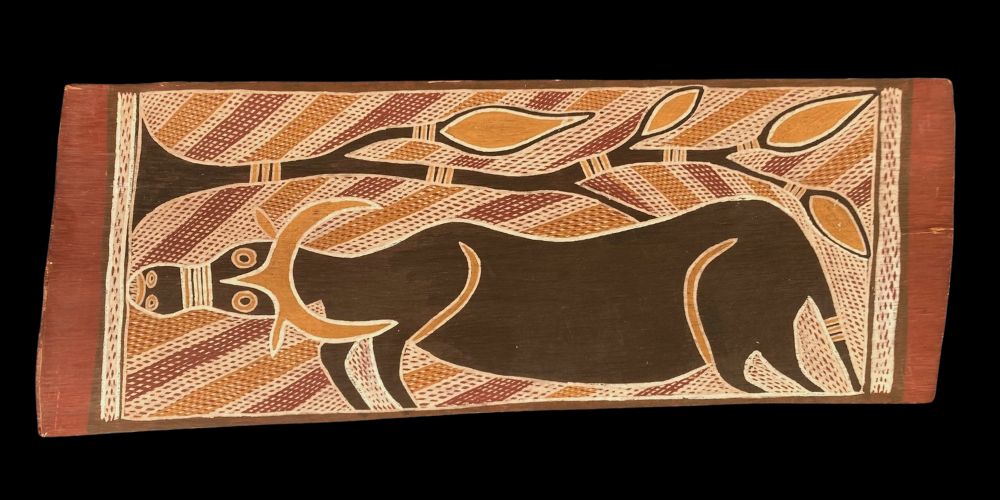

Animal Art Images

Some Aboriginal Animal Artworks which I have taken photos of and are free to be used (but please acknowledge the original image Creator, the artist)

Please click on Link for higher quality images

Buffalo by unknown Yirrkala artist

Please click on Link for higher quality images