Crusoe Kuningbal Master of the Mimih spirit

Crusoe Kuningbal (c. 1922–1984) also known as Guningbal is recognised as one of the most innovative Aboriginal artists of Western Arnhem Land. Renowned for his pioneering Mimih spirit sculptures and distinctive bark paintings, Kuningbal helped redefine the boundaries of Kuninjku art, blending ceremonial tradition with bold individual vision.

Operating primarily from Barrihdjowkkeng near Maningrida, Kuningbal introduced sculptural depictions of ancestral Mimih spirits to the art market—a revolutionary gesture that would influence generations of artists, including his sons Crusoe Kurddal and Owen Yalandja. His works, unmistakable in style and spiritually resonant, have become highly sought after by collectors worldwide.

Whether you’re researching an artwork, seeking authentication, or curious about the value of a Crusoe Kuningbal sculpture or bark painting, this guide offers expert insight into his style, significance, and legacy. If you believe you own a Crusoe Kuningbal artwork, feel free to contact me. I am always looking to acquire authentic pieces and would be delighted to view a JPEG and provide a valuation.

Crusoe Kuningbal Sculpture and Bark Painting Style

Sculptural Hallmarks

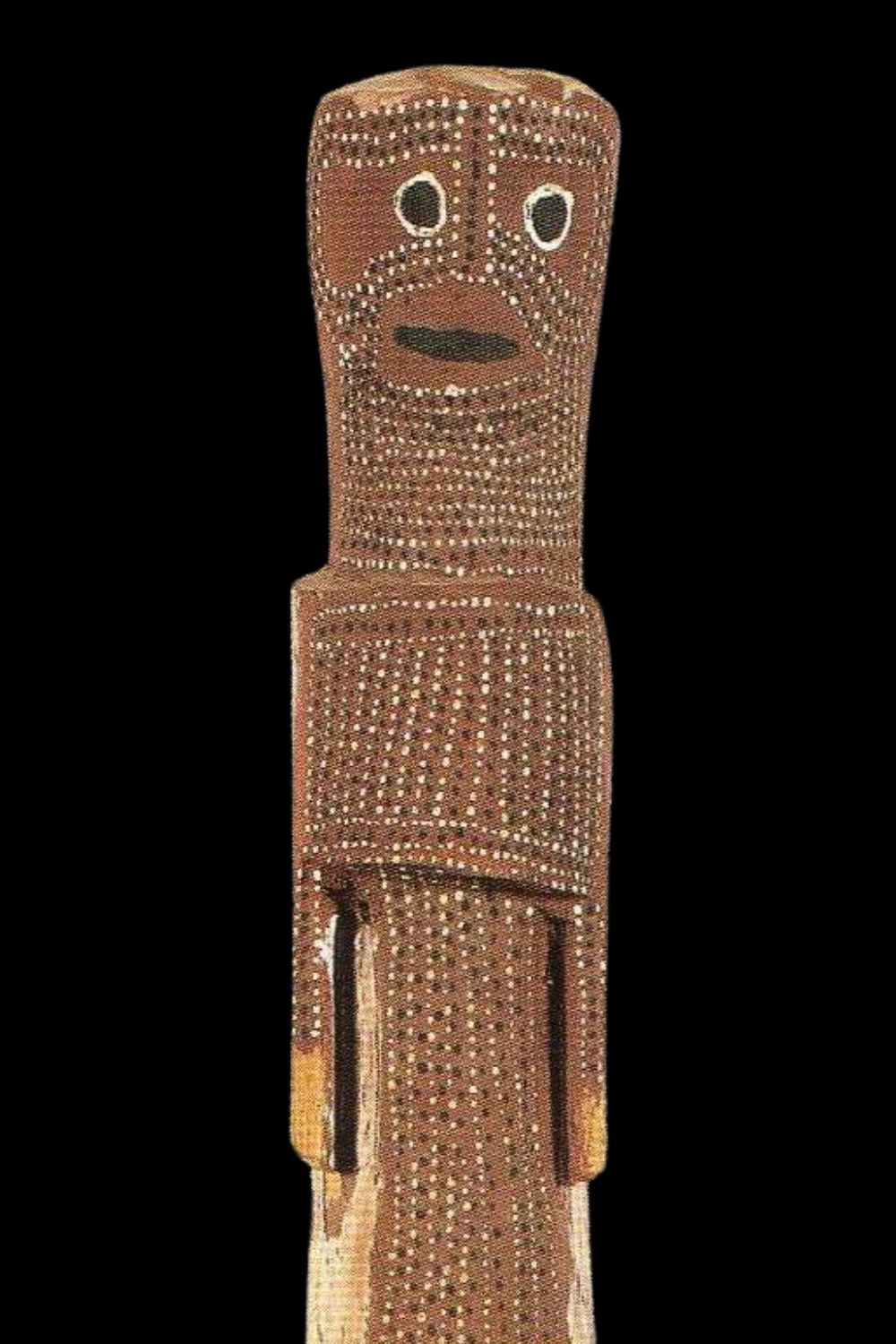

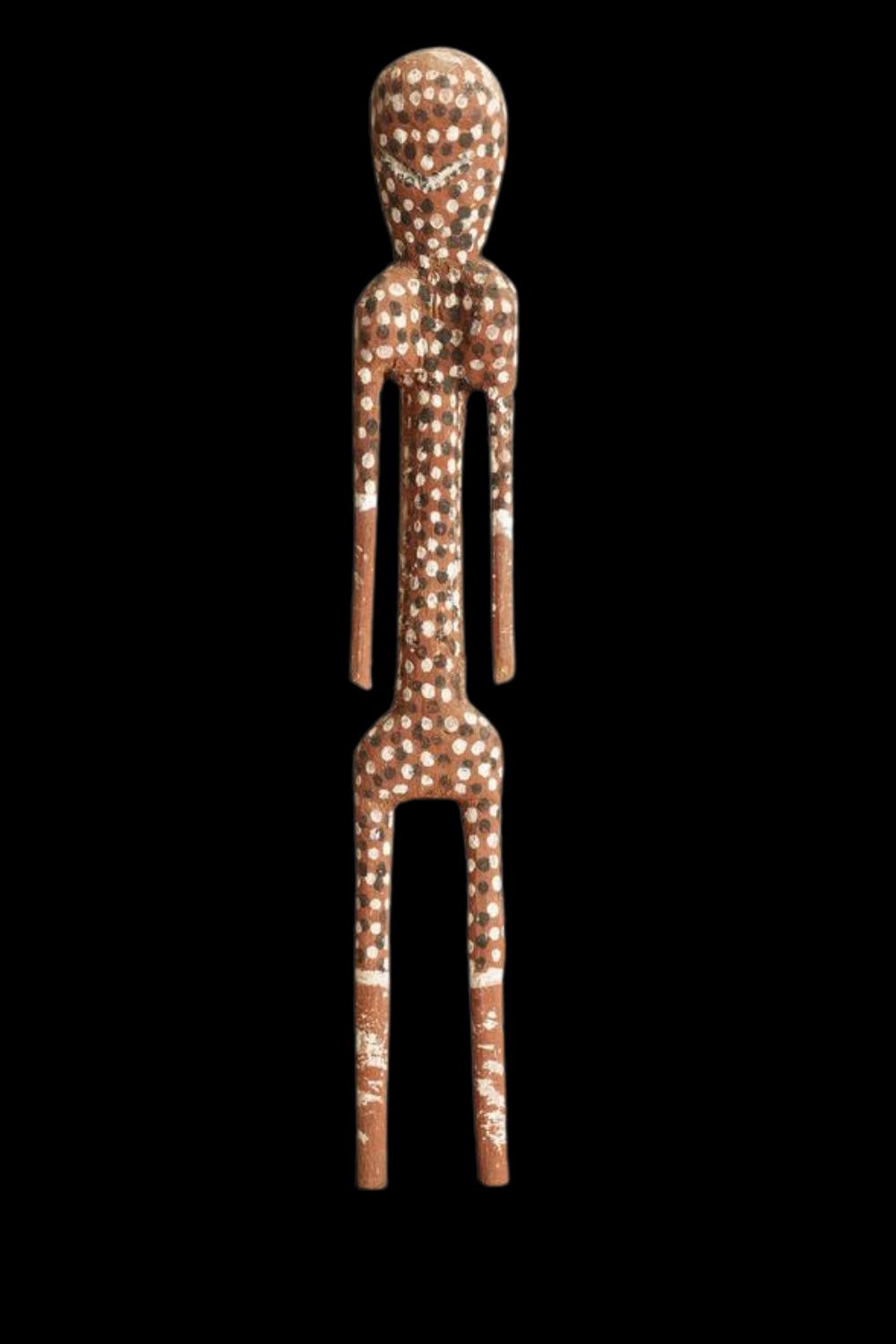

Crusoe Kuningbal’s Aboriginal sculptures are visually commanding, featuring tall, elongated forms that evoke the supernatural grace of the Mimih spirits. These slender spirit beings, central to Kuninjku belief, are rendered with precise stylistic consistency:

- Form: Each figure is carved from a single piece of native hardwood, typically stringybark or softwood. The body is elongated far beyond natural human proportions, with a small round head and short limbs—reflecting the fragile, otherworldly appearance of Mimih spirits.

- Surface Decoration: Kuningbal painted his sculptures almost exclusively in red ochre, overlaid with dense patterns of white and black dotting. Unlike many Arnhem Land artists, he avoided fine rarrk (cross-hatching), opting instead for dotting to build texture and volume.

- Limbs: The hands and feet are often minimally detailed or left unpainted, reinforcing the vertical emphasis of the figure.

- Facial Features: Eyes and noses are painted rather than carved, lending an expressive mask-like quality to the spirits’ faces.

These sculptures were not initially created for commercial purposes. They were first made in the late 1960s to accompany Mamurrng ceremonies—a type of regional trade and diplomacy festival—where Kuningbal would sing and dance with his creations in performance.

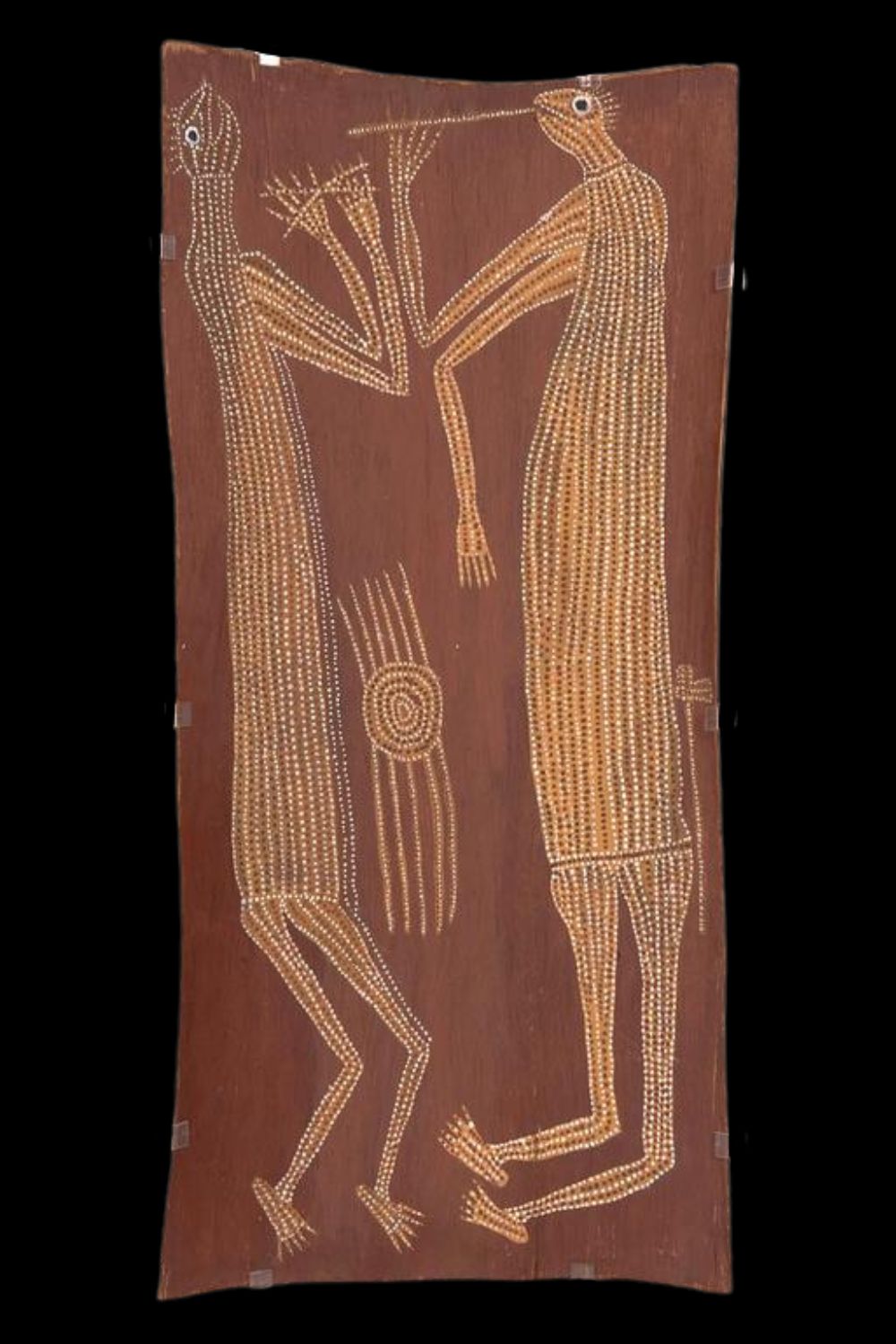

Bark Paintings

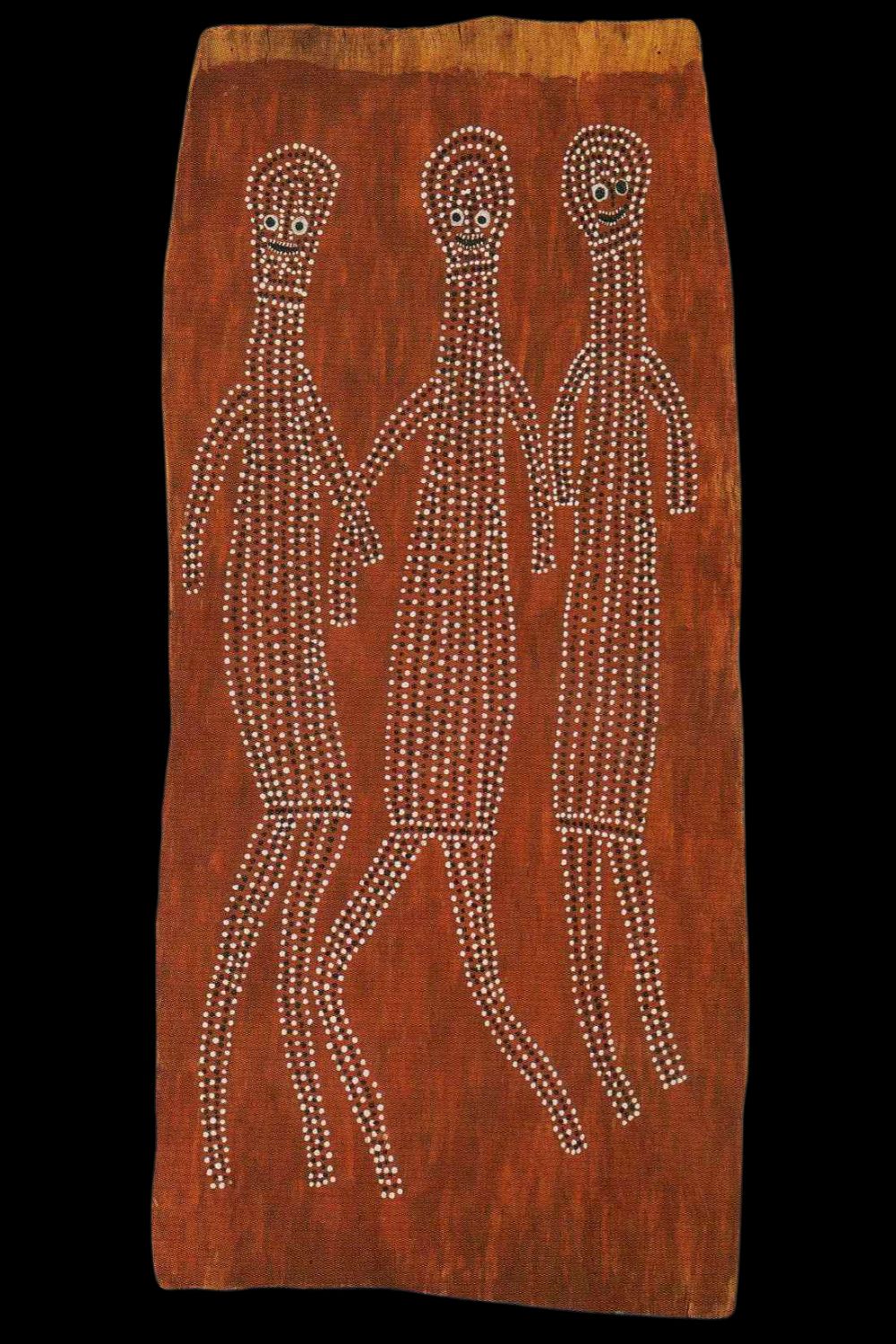

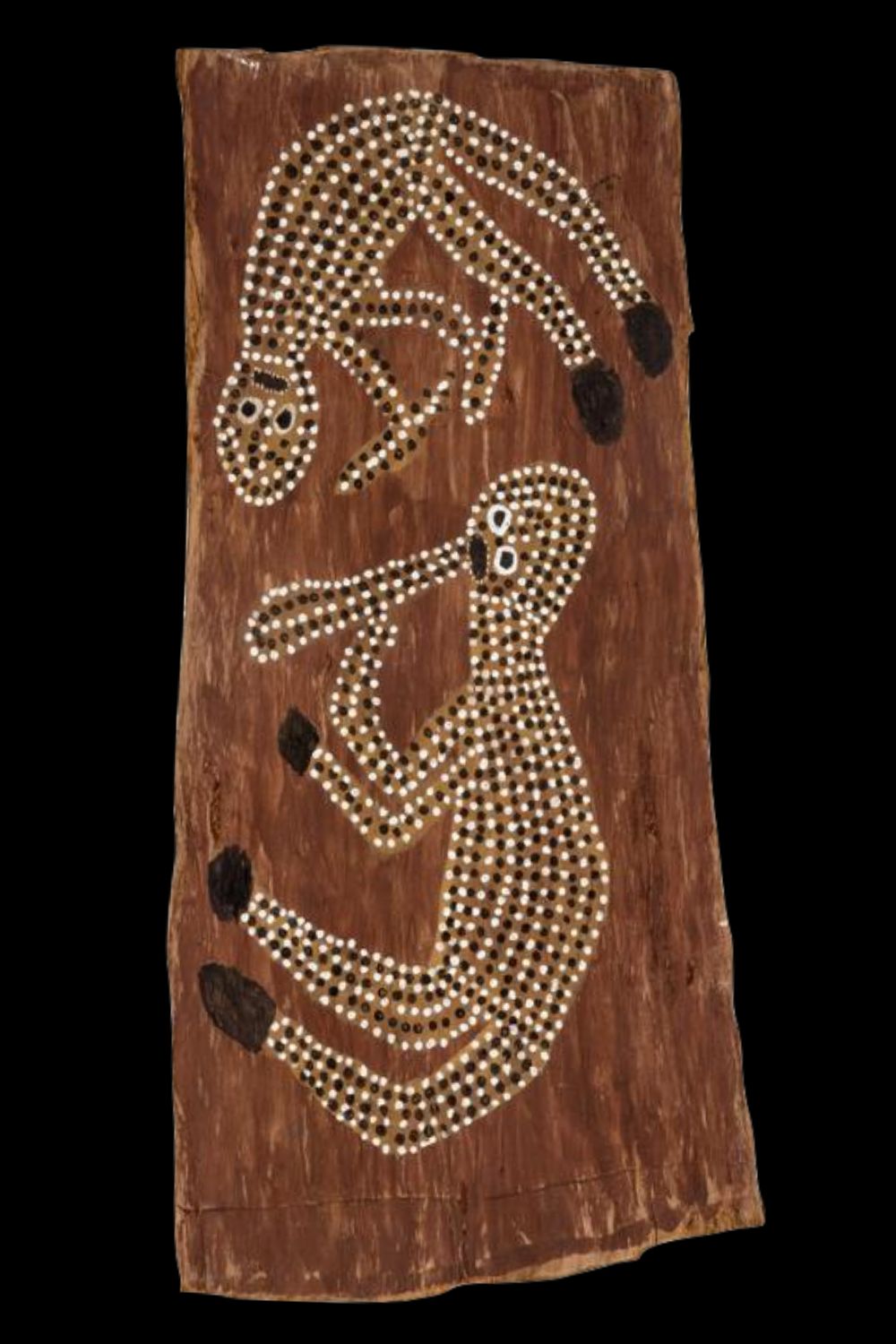

While most collectors know Crusoe Kuningbal for his sculptures, his bark paintings are no less significant. His bark works feature similar stylised Mimih figures, often shown standing or dancing in profile.

- Technique: Kuningbal didn’t used the intricate rarrk technique that characterises many Arnhem Land painters. Instead, he employed fine dots—usually white—set against red ochre or black backgrounds to outline his spirit figures.

- Subject Matter: Mimih spirit are the dominant theme, though other ancestral beings such as Yawk Yawk (female water spirits) and Totemic animals exist.

- Composition: Figures often dominate the bark’s vertical surface, isolated without background scenes, enhancing their mystical presence.

His bark paintings display remarkable consistency with his sculptures—both in subject matter and stylistic expression—making it easier for connoisseurs to identify his hand across media.

Biography: Crusoe Kuningbal

Early Life and Cultural Foundations

Crusoe Kuningbal was born around 1922 in the Middle Liverpool River region of Western Arnhem Land. He belonged to the Kuninjku language group and grew up immersed in the rich ceremonial life of his community. Like many men of his generation, he spent time working in buffalo-shooting camps in the bush, gaining a reputation as a physically capable and respected young man.

During World War II, the Kuninjku people—including Kuningbal—relocated to the Milingimbi Mission, which became a hub for artistic and cultural exchange. After the war, Kuningbal returned to his homelands near Maningrida and began painting bark to sell through the local trading post. It was here that he began developing a unique visual language that would set him apart from his peers.

Innovation and legacy: Mimih Spirit Sculptures

In 1968, Kuningbal produced what are believed to be the first sculptural representations of Mimih spirits ever created for sale. Though the spirits themselves had long existed in oral tradition and ceremonial practice, their depiction in three-dimensional form was a radical departure.

Kuningbal’s first Mimih sculptures were created for performance at Mamurrng ceremonies, where he danced with them and sang ancestral songs. These events impressed local audiences and mission staff alike, prompting growing interest in the works as collectable objects. By the early 1970s, Kuningbal’s Mimih sculptures were being collected by museums and private buyers across Australia.

Kuningbal settled at Barrihdjowkkeng outstation with his wife Lena Kuriniya. Together they raised three sons—Crusoe Kurddal, Owen Yalandja, and Tim Wulanibirr—all of whom would become artists in their own right, continuing the sculptural traditions their father pioneered.

Crusoe Kuningbal died in 1984, but his artistic legacy remains deeply embedded in the fabric of Kuninjku art. His influence is visible in the work of his descendants, as well as in that of contemporaries and collaborators

Above: Early examples are small often less than 50 cm but they are also extremely rare

Influence on Later Artists

The success of Kuningbal’s Mimih sculptures paved the way for a flourishing school of painted wooden sculpture in Maningrida. His sons Crusoe Kurddal and Owen Yalandja have developed and expanded the Mimih form, introducing even more intricate surface decoration, including scale-like dotting and expressive body movement.

These sculptural traditions have since become one of the most iconic art forms to emerge from Arnhem Land, collected by institutions such as:

- The National Gallery of Australia

- Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia

- Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Musée du quai Branly, Paris

Kuningbal’s sculptural innovations also influenced bark painters such as January Nangunyari and Spider Nabuna, who began to depict Mimih spirits with a similar dotting technique.

Conclusion

Crusoe Kuningbal stands as a foundational figure in the history of contemporary Aboriginal sculpture. Through his Mimih spirit carvings and distinctive bark paintings, he bridged ceremonial practice and artistic innovation—leaving a legacy that continues to animate the art of Western Arnhem Land.

Whether encountered in a museum, a private collection, or through the work of his descendants, Kuningbal’s vision remains unmistakable: grounded in lore, alive with spirit, and eternally reaching skyward.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Meaning of Kuningbal

Crusoe artworks

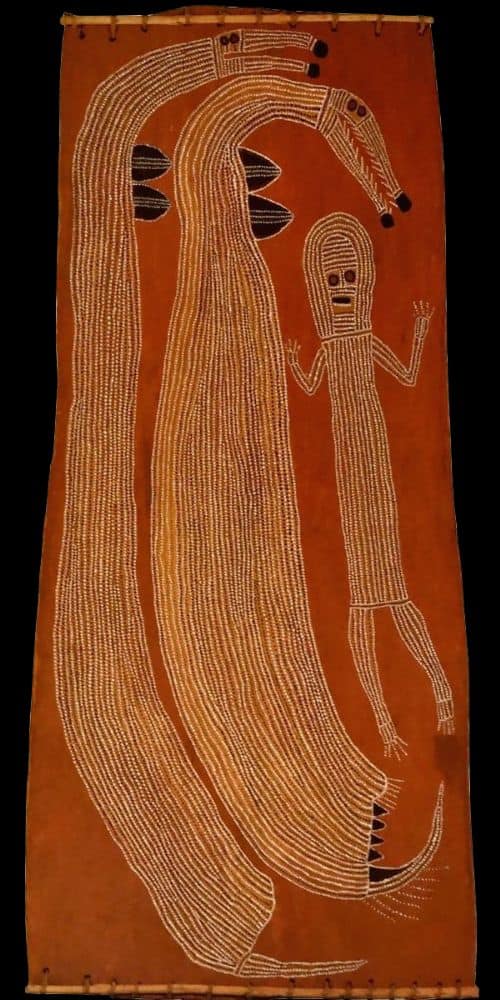

The Rainbow Serpent

Aboriginal people believe that Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent, created many sacred sites in Arnhem Land. Characteristics of Ngalyod vary from group to group and also depend on the site. He can change into a female serpent, and has both, powers of creation and destruction. Ngalyod is most strongly associated with rain, monsoon seasons, and the rainbows that arc across the sky like a giant serpent. He is most active in the wet season. In the dry season, he rests in billabongs and freshwater springs. When he rests he handles the production of water plants such as waterlilies, vines, algae, and cabbage tree palms.

When waterfalls roar down deep gorges, that Ngalyod is calling out. Large holes in stony banks of rivers and cliff faces are his tracks.

The rainbow serpent is deeply respected because it will swallow people who offend him. If Ngalyod swallows people during floods that he has created, he regurgitates them and they transform into new beings by his blood.

Aboriginal people respect sacred sites where the Rainbow Serpent resides. Near these sites, cooking is not allowed. Cooking near the resting place of the great serpent will incur his wrath. Ngalyod can cause sickness, accidents and great floods, which make it easier for him to swallow his victims.

Although Ngalyod is generally feared throughout the Stone Country, he is a friend and protector of the tiny Mimi Spirits.

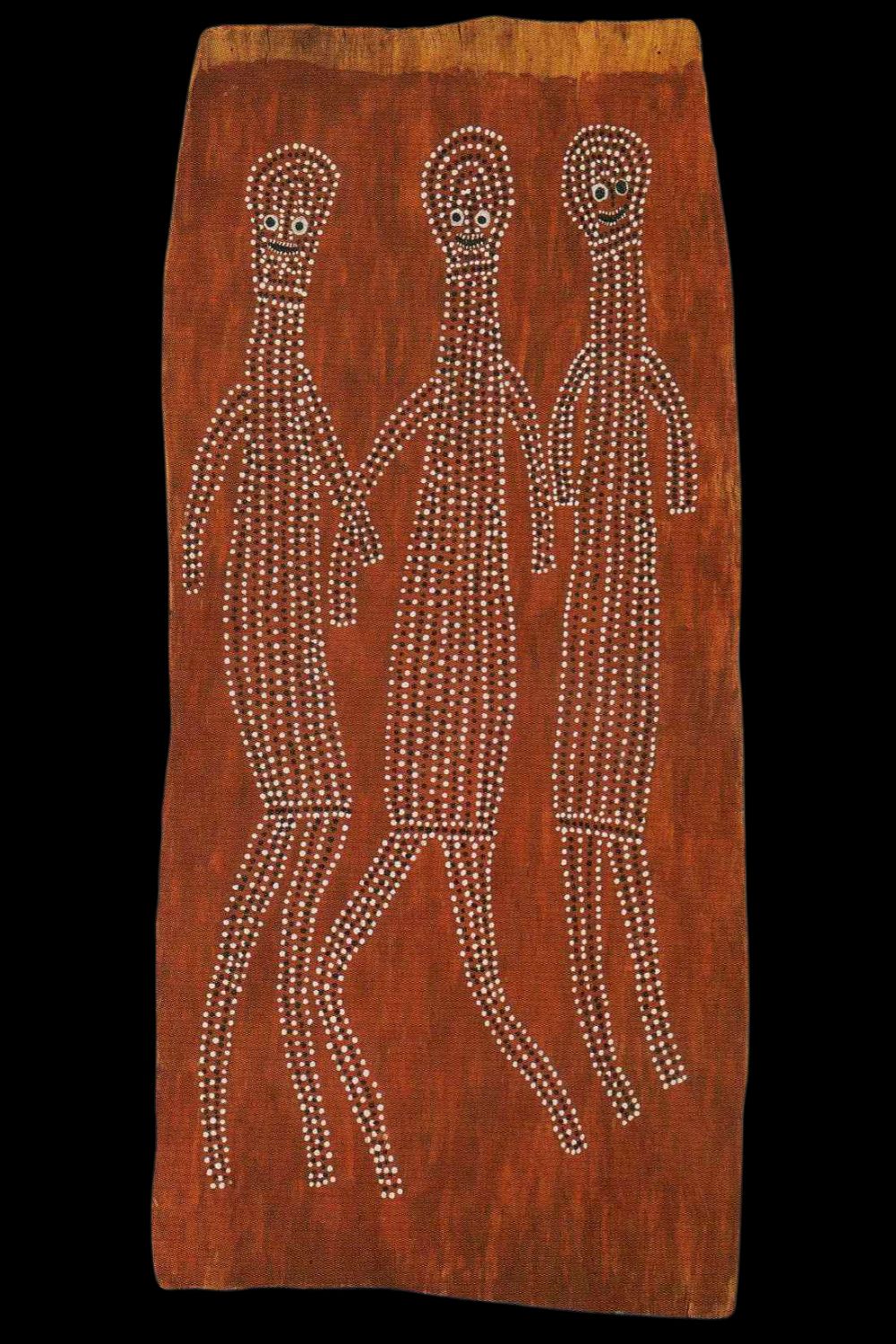

Mimih Spirits: Custodians of Culture in Western Arnhem Land

In the ancient sandstone escarpments of western Arnhem Land, the Mimih—supernatural ancestral beings of immense cultural importance—are said to have once inhabited the rock crevices and high stone shelters of the plateau. These ethereal figures, whose bodies are described as impossibly slender and delicate, were so finely built that even a gust of wind could carry them away. Despite their spectral appearance, Mimih are considered beings of flesh and blood, not spirits in the Western sense, but rather part of the physical and ancestral landscape of the Bininj people.

Within the cosmology of western Arnhem Land, the Mimih are revered as the first teachers—the original civilising agents who imparted crucial knowledge to the earliest Aboriginal people. They taught how to hunt and butcher game, prepare food, and make tools. More significantly, they are credited with bestowing the foundational aesthetic and ceremonial traditions of the region: the dances, the songlines, and the art forms that continue to define the cultural identity of western Arnhem Land communities to this day. The distinct rhythmic movement, melodic structures, and ceremonial body adornment known as the “Mimih style” remain in practice, a living legacy of these ancestral beings.

Mimih society is believed to have mirrored human social organisation, yet it predated human existence. They lived in structured communities, engaged in ceremonies, and followed kinship systems that later became the basis for Aboriginal clan life. In this sense, the Mimih represent more than mythological figures—they are cultural archetypes, embodying the knowledge systems, moral codes, and creative expression that form the bedrock of Aboriginal civilisation in western Arnhem Land.