Mick Kubarkku: Traditional Oenpelli Artist

Tribe: Kunwinjku

Clan: Kulmarru

Country: Yikarrakkal, Mann River, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory

Lifespan: Circa 1925 – 2008

Among the great painters of Western Arnhem Land, Mick Kubarkku (also spelled Kuparrku or Kubarrku) stands as a visionary custodian of rock art tradition—an artist whose works bridge the sacred and the contemporary, the ceremonial and the collectible.

Born around 1925 at Kukabarnka, an escarpment site near the Liverpool River, Kubarkku’s early life was defined by the nomadic rhythms of Kunwinjku family life. He travelled extensively with his family across ancestral lands between the territories of his father and mother, with seasonal returns to Yikarrakkal on the Mann River. This deep immersion in Country and culture would later surface as the core of his artistic visio

If you have a Mick Kubarkku bark painting to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your bark painting is worth to me please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

Ancestral Inheritance and Early Painting Practice

Kubarkku’s first paintings were not created for outsiders. His initiation into art was through the rock shelters and bark walls of the bush, where he assisted and observed his father, Ngindjalakku, a ceremonial leader and painter. These early compositions were expressions of ritual, designed for spiritual function rather than aesthetic contemplation.

It was not until circa 1957, following his relocation to the settlement of Maningrida, that Kubarkku began to paint on bark for the purpose of exchange. In this context, bark paintings were offered in return for tobacco, flour, or tools—humble transactions that would ultimately lead to the preservation of a sacred visual language. Together with fellow painter David Milaybuma, Kubarkku became one of the first Arnhem Land artists to establish a regular painting practice for public circulation.

Despite these new audiences, Kubarkku never diluted his cultural obligations. He remained the senior man of the Kulmarru clan and was regarded as a knowledge custodian and guardian of sacred sites across his ancestral lands. His artistic practice remained fundamentally ceremonial in nature, charged with metaphysical authority and spiritual depth.

Last of the Rock Art Interpreters – Keeper of Spirit Imagery

Mick Kubarkku—also known in some records as Kuparrku or Kubarrku—stands among the final generation of Arnhem Land painters with direct knowledge of the rock art galleries of Western Arnhem Land. Alongside peers such as Murra Murra and Bardayal Nadjamerrek, he carried forward an unbroken lineage of sacred visual storytelling, interpreting figures once painted on stone surfaces into the medium of eucalyptus bark.

His style is often described as semi-traditional, but this term belies the deep ceremonial origins of his practice. While drawing inspiration from Oenpelli rock art, Kubarkku introduced key innovations that distinguished his bark paintings in both technique and iconography.

Figurative Space and Compositional Balance

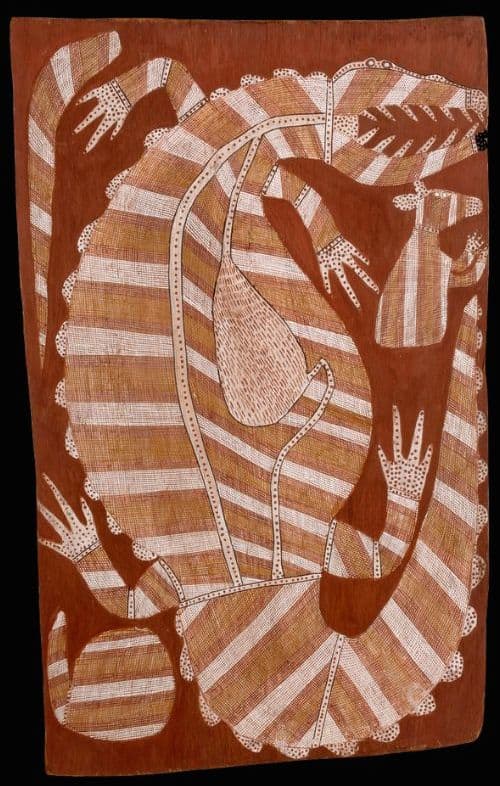

Kubarkku’s paintings are typically figurative in nature, and often portray spirit beings and totemic animals. A unique feature of his compositions is the distinctive negative space that surrounds his central figures, creating a tension between form and void that imbues the works with ethereal weight. Unlike the sinuous or fluid contours of earlier rock art, Kubarkku’s spirits are often constructed with angular, articulated joints, their limbs static and poised.

Iconic Features

- White-spotted faces: Many of Kubarkku’s spirits feature blank, rounded faces daubed with white dotting, suggestive of ceremonial body paint.

- Facial minimalism: Eyes and other facial features are frequently omitted, allowing the figures to appear otherworldly or anonymous.

- Non-wavy limbs: Kubarkku’s spirit figures typically display sharply angled elbows and knees, lending a sculptural formality to their movements.

Large-Scale Bark Paintings and Sculptures

In his later years, Mick Kubarkku began producing exceptionally large bark paintings, some exceeding 1.3 metres in length. These monumental works feature spirit figures interwoven with ceremonial rarrk patterns, often referencing the Mardayin ceremony, a major mortuary and initiation rite among the Kunwinjku.

In addition to bark paintings, Kubarkku also created sculptural works, including carvings of mimih spirits and painted hollow log bone receptacles (also known as lorrkon), used in secondary burial ceremonies. These three-dimensional pieces demonstrate his fluency across media, all rooted in ceremonial function.

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

References and Extra Reading

Keepers of the secrets: Aboriginal art from Arnhemland

Crossing Country: The Alchemy of Western Arnhemland art

The Rainbow Serpent

Aboriginal people believe that Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent, created many sacred sites in Arnhem Land. Characteristics of Ngalyod vary from group to group and also depend on the site. He can change into a female serpent, and has both, powers of creation and destruction. Ngalyod is most strongly associated with rain, monsoon seasons, and the rainbows that arc across the sky like a giant serpent. He is most active in the wet season. In the dry season, he rests in billabongs and freshwater springs. When he rests he handles the production of water plants such as waterlilies, vines, algae, and cabbage tree palms.

When waterfalls roar down deep gorges, that Ngalyod is calling out. Large holes in stony banks of rivers and cliff faces are his tracks.

The rainbow serpent is deeply respected because it will swallow people who offend him. If Ngalyod swallows people during floods that he has created, he regurgitates them and they transform into new beings by his blood.

Aboriginal people respect sacred sites where the Rainbow Serpent resides. Near these sites, cooking is not allowed. Cooking near the resting place of the great serpent will incur his wrath. Ngalyod can cause sickness, accidents and great floods, which make it easier for him to swallow his victims.

Although Ngalyod is generally feared throughout the Stone Country, he is a friend and protector of the tiny Mimih Spirits.

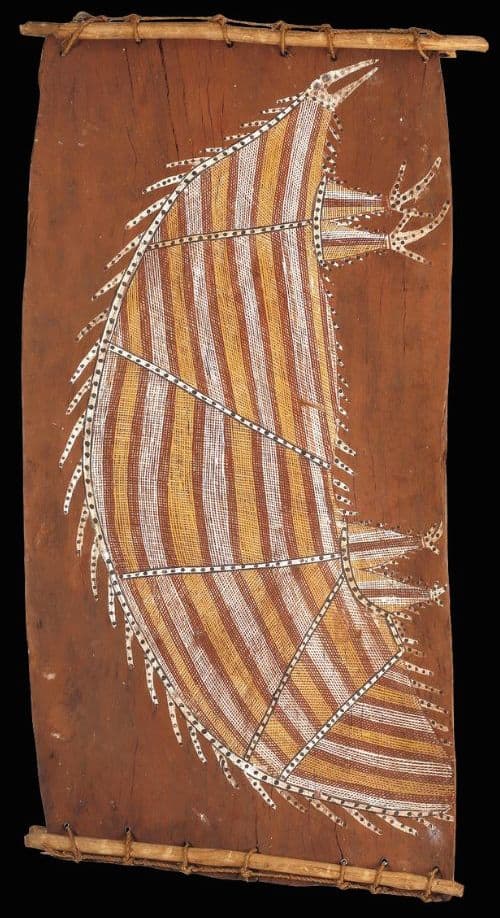

Ngarrbek, the Echidna

Namanjwarre the Crocodile

Namanjwarre, the saltwater crocodile, Corcodylus porosus. The crocodile totem Namanjwarre is a Yiridja moiety totem.

The estuarine crocodile or Namanjwarre is the protector of the sacred objects of the Mardayin ceremony. The Mardayin ceremony is an important rite of passage for Kuninjku language speakers of Western Arnhem Land. Namanjwarre would devour anyone who transgressed from the correct ceremonial protocol.

The upper Liverpool River and Maragalidban Creek areas had lots of these crocodiles. Crocodiles are rarely killed for food but their eggs are sought after during the wet season when the females are nesting. A major crocodile sacred site exists near the outstation of Kurrindin, in the Liverpool River District.

The treatment of the infill of Namanjwarre is the same used on Mardayin ceremonial objects. Mardayin objects decorated with the same bright patterns of crosshatching and dotted lines. Mardayin objects are secret and sacred. The use of the same design within the crocodile, thus, shows the interconnection of the crocodile and the Mardayin ceremony.

Namanjwarre is an important totem and is danced in the sacred and secret ritual of the Mardayin ceremony.

Yawkyawk – Ancestral Beings of the Freshwater Dreaming

In Western Arnhem Land, the Yawkyawk — known in Kunwinjku as Ngalkunburriyaymi — are among the most revered and visually captivating ancestral beings. These freshwater mermaid spirits inhabit the deep, shaded waterholes of the stone country, embodying the life-giving mystery of water, the origins of creation, and the fertility of the land.

Half-human and half-fish, Yawkyawk are feminine ancestral figures often depicted with long, flowing hair fashioned from water lilies or trailing aquatic plants, and the sinuous tails of fish or eels. As guardians of sacred water sources, they serve as potent totemic symbols of fertility — sustaining both human communities and the natural world.

Shapeshifters by nature, Yawkyawk can assume many forms: a graceful woman, a frog, or even the waterhole itself, with only their distinctive lily-like hair visible above the surface. Their Dreaming narratives are deeply connected to other central ancestral figures, including the Rainbow Serpent and the Wagilag Sisters, and while each clan holds its own variation of these stories, they share enduring themes of transformation, moral law, and creation.